Heroes of Autism: Forrest Gump

No matter what they say, the idiot from Greenbow, Alabama is actually not so dumb.

Note: This is the first in what I hope will be a series of many posts about autism. Over the years, I’ve noticed that there are a few particularly notable characters in American pop culture that provide a good representation of what autism looks like “in real life,” and I want to both explain and provide context for how I’ve recently come to grips with my own diagnosis of autism.

I want people to understand what it feels like “on the inside” and to be able to recognize it on the outside when they see it and what to do when they meet someone with autism.

Forrest Gump is one of the more famous characters in American cinema who is portrayed as a complex person most people think of as a fool.

In the film, he is called a “retard” twice, an “idiot” twice, and “stupid” 12 times, including by his own friends. (His football coach even calls him “the stupidest son of a b*tch alive.”)

He’s a simpleton with a low I.Q. who asks basic questions, provides basic answers, and goes through life not understanding why people do what they do. People treat him horribly on a regular basis, yet most of the time, he’s not perceptive enough to understand just how poorly they think of him.

The first time I saw Forrest Gump, I was 15 years old. At the time, I thought it was the best movie I had ever seen. This week, I watched it again. Even 24 years later, I still think it’s the best movie I have ever seen.

Better than any other film, Forrest Gump (the movie) showcases how “normal” people in society treat someone who doesn’t fit neatly within the lines of what they consider acceptable. Almost everybody Forrest Gump (the character) knows treats him very, very poorly. They are horrible to him.

They don’t appreciate the nice things he does, they don’t understand what he says, and they’re emotionally and verbally abusive to him, constantly insulting him for not being able to keep up with them intellectually.

Yet he keeps coming back to them, always remaining friends, never holding grudges, and not understanding why they were upset with him in the first place. It’s a gift, in a way, for him not to be able to fully understand the social stigma that surrounds him: it allows him to view things objectively without his feelings being hurt.

If you don’t know you’re the butt of a joke, you can’t be offended when people around you start laughing. You might even laugh too, not knowing it’s at your own expense.

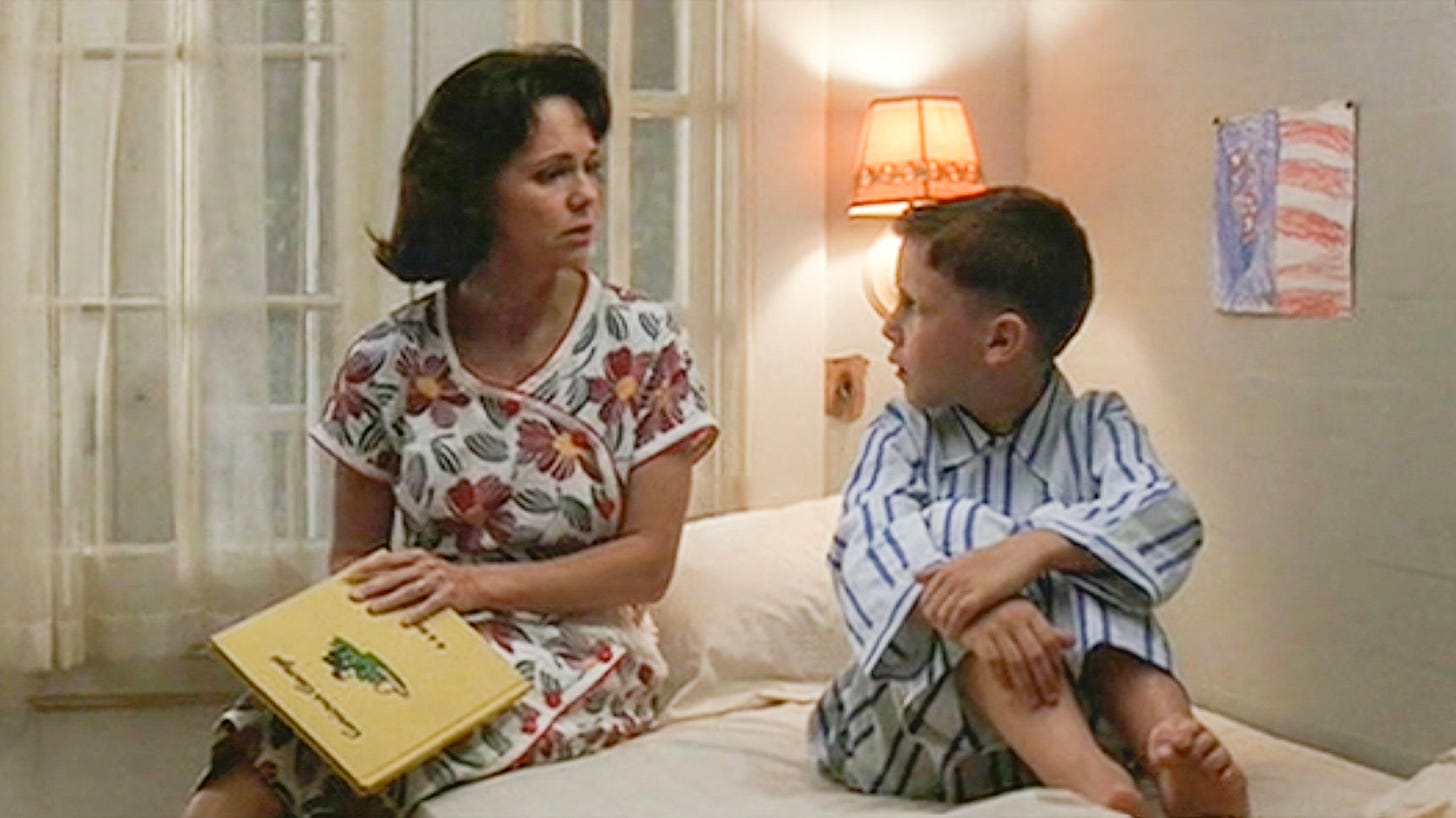

Forrest Gump, like many other characters in movies about social outcasts, is never explicitly labeled as “autistic” or diagnosed with autism. The only thing that’s specifically stated about his condition is when the school principal tells Momma that he’s not smart enough to get into the school.

“Your boy's different, Mrs. Gump. Now, his I.Q. is seventy-five. The state requires a minimum I.Q. of eighty to attend public school, Mrs. Gump. He's gonna have to go to a special school.”

So all we “officially” know about Forrest is that his I.Q. is so low that he isn’t eligible to go to a “normal” school. But, having said that, the movie is set in the 1950s, and American medicine had nowhere near the understanding of mental conditions and developmental disorders it does today.

The chances that a doctor would have even understood austism when Forrest tried to get into school circa 1956 are zero, let alone him having the ability to use that term and explain it to his mother.

Back then, they would have simply labeled Forrest “dim-witted,” “feeble-minded,” “mentally retarded” or just “different.”

But I’m going to say Forrest Gump had autism.

Although he’s a fictional character, he’s real enough in the story, and his experience of being socially awkward, taking things literally, and maintaining a child-like wonder about everything even into his adult life are all completely in line with autistic traits.

Part of what immediately grabbed me when I saw the movie for the first time was how he understood the world around him in a very literal way: that absolutely resonated with me. But as a teenager, I didn’t struggle with intellectual concepts as Forrest did, so I never would have thought, “Oh, I’m just like him.” Because I wasn’t. But there were definitely profound similarities.

Forrest’s I.Q. is very low: 75, which is around the 16th percentile. So he isn’t “smart.” He admits this himself when he tells Jenny, “I'm not a smart man, but I know what love is.” And there, he’s correct. He is not a smart man. But he does know what love is.

In my case, I never struggled with a low I.Q. — people certainly treated me like I was stupid and definitely called me stupid, but when I finally took an I.Q. test last year, I was pleased to find out that I was, in fact, not stupid and didn’t have any problems with intellectual capacity.

(Although, as I discovered, not actually being stupid doesn’t mean people won’t treat you like you are.)

So, here are ten things I think are interesting and wonderful about Forrest Gump—things I believe make him a hero of autism.

#1: He doesn’t know when adults lie to him or why.

There’s a child-like innocence we all have when we’re very young, but most people grow out of it very quickly. Adults are especially bad at this. They lie all the time: to themselves, to other adults, and even to children, and they don’t think it’s a big deal.

When the principal asks Momma, “Is there a Mr. Gump, Mrs. Gump?” she answers with, “He’s on vacation.” This is a lie.

Later, Forrest asks about this: “Momma, what’s vacation mean?” She lies again, saying, “Vacation’s when you go somewhere, and you don't ever come back.”

He never challenges this. For all we know, even after Momma’s long gone, Forrest still thinks his daddy is “on vacation.” He can’t imagine how or why his Momma would ever lie to him about this (or anything else).

It’s not just Momma: Jenny lies to Forrest all the time, not so much explicitly, but by pretending her life is very different than it really is. She also leads him to believe that their relationship is a lot more than it truly is.

I’ve struggled with this throughout life: why do adults lie? Why do people say things that aren’t true? Why can’t they just admit the truth?

I still don’t know the answer to this, and it makes me feel exceptionally stupid when I find out that people have been lying to me, especially when it turns out that everyone else except me knew it.

#2: He doesn’t understand metaphors, slang, or idioms.

There are numerous examples of this in the movie, where people use specific kinds of language that don’t make sense to him.

Elvis Presley, “The King”

In the beginning of the film, he meets Elvis Presley and is told that he’s called “The King.” When he finds out that Elvis dies, he says: “Must be hard being a king.” This makes sense: why would people call someone a king if he isn’t a king?

Looking for “Charlie” in the Vietnam War

Later, while serving in the US Army in Vietnam, he says: “I got to see a lot of countryside. We would take these real long walks. And we were always lookin’ for this guy named Charlie.”

I admit, that’s kind of a corny line, but it is true that someone like Forrest might not understand that “Charlie” meant the “VC” or “Viet Cong.” A lot of times, people who use nicknames or slang like this don’t explain; they figure you already know what they’re talking about. I’ve always found this extremely annoying.

In my experience, people often just spew out acronyms or jargony terms and rarely explain them. When you ask them to explain, they treat you like you’re stupid.

You’re just supposed to know stuff.

How? Why? I don’t know. Nobody ever explains. Nobody ever asks. Everybody except me already knows the right answer, somehow. I find that very annoying. Forrest doesn’t understand it either, but he doesn’t even know to ask for more details.

Lt. Dan’s Missing Sea Legs

After Forrest gets his fishing boat and starts out in the shrimping business, his old buddy Lt. Dan visits him. While Lt. Dan sits in his wheelchair, they have an exchange.

Forrest: “Lieutenant Dan, what are you doing here?”

Lt. Dan: “Well, I thought I'd try out my sea legs.”

Forrest: “Well, you ain't got no legs, Lieutenant Dan.”

Lt. Dan: (Annoyed) “Yes, I know that... you wrote me a letter, you idiot.”

I always hated it when people spoke like this. Why do people say things that don’t make any sense? Why does a man who doesn’t have legs use a phrase like “sea legs,” then act offended when you remind him about that obvious truth? This is strange.

#3: He takes everything literally.

Similar to above, it’s hard for Forrest to understand why people say things they don’t actually mean. Or that they say things they don’t mean literally. This is one of the most difficult parts of living in world of “normal” people.

For some reason, they’ll tell you things and you have to decide what they actually meant by what they said. It’s an annoying game, and it makes people like me (and Forrest) look stupid when we get it wrong.

He moons President Johnson

He goes to the White House for a ceremony to receive the Medal of Honor, and is presented with a strange request.

Johnson: “I understand you were wounded. Where were you hit?”

Forrest: “In the buttocks, sir.”

Johnson: “Oh, that must be a sight. I'd kinda like to see that.”

So, when the President of the United States of America tells him he’d like to see his battle wound, he does what any person would do: shows him exactly what he requested to see. That makes sense, right? Why wouldn’t it?

Forrest turns around, pulls down his pants, and exposes his butt showing a bullet wound to the president.

And here’s the weird thing: members of the audience (and his friends watching on TV back home) gasp in shock and horror!

But why?

Was he, or was he not supposed to show LBJ his butt? The president asked him to, right? To be sure, it’s was a weird request, but the president is the one who did the weird thing, not Forrest. How was Forrest supposed to know he was joking?

President Johnson walks away in shame, shaking his head and muttering “Goddamn, son,” under his breath, as though Forrest was an idiot for doing what he literally just told him to do.

How does anybody ever know when someone is joking? Why are we supposed to just know this stuff inherently? Why does this seem to obvious to everyone except me (and Forrest)?

He thrills his drill sergeant

This is a good thing: when he joins the army, he is in the barracks cleaning his gun (or stripping and assembling it or whatever). He does an excellent job of course, because he’s detailed and fastidious, and is good at following orders. He’s so good, in fact that his drill sergeant is shocked, and doesn’t even know what to say to him.

He shouts out: “GUMP! Why did you put that weapon together so quickly, Gump?”

Forrest looks at him with confusion, and responds with the most obvious answer possible. He feels as though it’s a stupid question, though, and he’s almost afraid to answer it. He answers the question with a question.

“You told me to, Drill Sergeant?”

The drill sergeant is astonished at this answer which he seems to find exceptionally wise and smart.

Why do people ask dumb questions like this? The drill sergeant tells him to do something, so he does it. Then the drill sergeant asks him why he did it. Huh? Is this a trick question?

He unwittingly insults Lt. Dan

When they’re recovering from their battle wounds in the military hospital, Lt. Dan crawls over to Forrest’s bed in the middle of the night and pulls him down onto the ground and starts screaming at him.

Lt. Dan: “Now, you listen to me. We all have a destiny. Nothing just happens, it’s all part of a plan. I should have died out there with my men! But now, I’m nothing but a goddamned cripple! A legless freak.

Look! Look! Look at me! Do you see that? Do you know what it's like not to be able to use your legs?”

Forrest: (Hesitates) “Well... Yes, sir, I do.”

Here, Lt. Dan is asking if Forrest knows what it’s like to not be able to use his legs. Of course, Forrest does know—he uses leg braces in the early part of the film—so he gives him the answer to his question, which is accurate, literal, and exact.

But Lt. Dan doesn’t want to hear this, because he doesn’t know that Forrest ever had trouble walking. He’s too self-absorbed to know (or ask) anything about anyone except himself.

So he gets angry when Forrest answers him with the correct answer because he thinks Forrest isn’t listening to him.

Lt. Dan: “Did you hear what I said? You cheated me. I had a destiny. I was supposed to die in the field! With honor! That was my destiny! And you cheated me out of it! You understand what I’m saying, Gump? This wasn't supposed to happen. Not to me. I had a destiny. I was Lieutenant Dan Tyler.”

Forrest: “You… you still Lieutenant Dan.”

Here, Lt. Dan figures he misunderstood his question, so he asks, “Did you hear what I said?” — he believes Forrest doesn’t understand him. But, of course, he does.

Next, he says Forrest cheated him out of his destiny. When he asks, “You understand what I’m saying, Gump?” Forrest doesn’t understand. How could he? He saved the man’s life, and now he’s shouting at him in anger? That doesn’t make any sense at all.

Finally, Lt. Dan implies that he is no longer “Lt. Dan Tyler.” Forrest reminds him, of course, that he’s still Lt. Dan, on or off the battlefield.

Lt. Dan doesn’t want to hear this, either, and looks at him like he’s an idiot for saying so, then crumples on the floor in disgust.

#4: He’s keenly aware of details and numbers.

Right after he tells the woman on the bus stop bench about how Jenny died he asks: “Didn’t you say you were waiting for the Number Seven bus?”

She was so absorbed in his story that she completely lost track of time, and which bus she was waiting for. Forrest didn’t skip a beat at all — he was carefully watching not just for his bus, but for hers as well.

By now, she doesn’t mind being late, and so she just says “There’ll be another one along shortly.”

Later, when he tells Bubba’s mother about the plan to keep his promise to Bubba by going into the shrimping business (even after Bubba died), he counts off the amount of money he has left over from the $25,000 he earned by doing a ping pong paddle endorsement.

“I’m taking the $24,562.42 that I got that's left after a new haircut and a new suit, and I took Momma out to real a fancy dinner, and I bought a bus ticket and three Dr. Peppers.”

Elsewhere, he remembers incredibly specific things, especially dates and numbers:

Speaking to Jenny’s grave: “You died on a Saturday morning.”

Talking about Momma: “She had got the cancer and died on a Tuesday. I bought her a new hat with little flowers on it.”

Talking about running: “I had run for three years, two months, fourteen days, and sixteen hours.”

This is very typical for people with autism. Personally, I’m not a genius with numbers, and I never have been. Math is really, really hard for me. But for whatever reason, I can remember incredibly specific details, mostly things like people’s names: I’m pretty sure I can remember the first and last names of every person I’ve met in my entire life.

Even if I met you 35 years ago, when I was four years old, I might still remember your name, your face, where I met you, and something else about you, like how you had a parrot named Sweet Pea or that you liked to wear OshKosh B’gosh overalls.

People are often amused by this and find it to be a weird party trick. I’ll meet someone that I met once, a long time ago—even after a decade or two—and they won’t remember me at all, but I’ll remember almost everything about them.

“Hi: you’re Nicolas Basurto. I remember you. We visited your house on Corte Madera drive. We had enchiladas for dinner. You had a puppet named ‘Jonathan,’ and you told us that if we were really good, you’d give us bubblegum ice cream later that night. Your son wore a backward Oakland A’s hat and had holes in the knees of his jeans.”

“WOW!!” People will say.

“YOU REMEMBER ALL THAT?”

This makes me red with embarrassment, like I’m stupid or something. I don’t understand this, and I’m weirded out by the fact that they don’t remember me or anything about me. It’s kind of insulting, really. Am I really that forgettable?

#5: He doesn’t get things that other people think are incredibly obvious.

He discovers he’s a father

Probably the best example of him needing to be explicitly told something other people would think is obvious is when Jenny tells him he’s a father.

We learn that (in perhaps their only sexual encounter up to that point) Jenny became pregnant and had a child. Forrest doesn’t know this, because Jenny moved away and he hasn’t seen her in years.

So, Jenny has his child but Forrest doesn’t even know he’s a father.

He comes to visit her, and sees that she has a son, which surprises him.

Forrest: “You're a momma, Jenny.”

Jenny: “I’m a momma. His name is Forrest.”

Forrest: “Like me!”

Jenny: “I named him after his Daddy.”

Forrest: “He got a daddy named Forrest, too?”

Jenny: “You’re his daddy, Forrest.”

This completely shocks and even frightens him. But the implication here is that if she had never told him that HE was little Forrest’s father, he would have simply just thought it was all a totally wild coincidence.

She has to come out and say the obvious thing… or what she thinks should be obvious.

This is completely in line with everything I know about autism. I accept things the way they are as you present them to me. I don’t suspect otherwise. Why would I?

I need you to connect the dots for me.

You can’t tell me something that you think points to a certain conclusion: if you want me to actually understand you, you have to tell me the conclusion, out loud, in addition to the steps leading up to it.

They tell him to run but forget to tell him to stop

This is actually one of my favorite parts of the entire movie. So much of the film’s story is based on him being told: “Run, Forrest! Run!” So he does. He runs.

But then they get weirded out by the fact that he doesn’t know to stop running. But how would he? They aren’t specific enough: they didn’t tell him how far to run, where to run, for how long, when to stop, or EVEN TO STOP AT ALL.

In the beginning, when he joins the football team in high school, they’re initially confused by the fact that he runs the football down the field, into the end zone, then keeps going. Why are they surprised?

Later, when he plays on the college football team, they’re more explicit: they still say “Run, Forrest! Run!” but then they also say: “Stop, Forrest! Stop!” They even put up a special sign that says “STOP FORREST” so he can recognize this.

I wish people would do more of this in real life. So many times, today, and growing up, I don’t understand why people say one thing and then assume you know the rest.

I remember going to a park once with my dad when I was around 8 years old. The local police department or sheriff’s office had some sort of “public safety fair” where there were rides and games and food. There was a big “McGruff the Crime Dog” mascot talking about “taking a bite out of crime.”

It was a fun event, and I was absolutely blown away when I found out the basketball game at a little booth where you tried to sink a basketball into the basket. If you did, you would win a frisbee. We got something like three tries to make a basket.

I picked up the basketball, and threw it, and, within my three tries, sunk one.

A bell rang! The woman clapped! She gave me a FREE frisbee! I was so giddy with excitement I couldn’t believe it: I had won a frisbee! This was amazing!

I asked her if I could play again, and she said I could. I picked up the ball. I sank it in the basket again. The bell rang again. The woman clapped again. I was on top of the world!

I reached out my hand for a second frisbee. That’s when this woman turned into an evil witch. She told me I couldn’t have another frisbee.

“Why not?” I asked, incredulous. “I made a basket!”

“Because you already have one,” she said, pointing to the frisbee she had given me just a minute or two earlier.

“But I made a basket!” I implored. “You said if I make a basket, I win a frisbee!”

“Well, you can only win one frisbee,” she said. “You can keep playing the game if you want, but there’s only one frisbee per person.” This was galling: it didn’t make any sense at all.

Why didn’t she tell me that in the first place?

Who made up those stupid rules? Why would I want to keep playing the game if I couldn’t get more frisbees? What was the point?

I remember crying, almost hysterically, at how unfair it was. My dad came and got me and dragged me back to the car, almost kicking and screaming. I was absolutely inconsolable. I was so confused and so hurt: she tricked me, and I felt like a fool.

How was I supposed to know? She never said anything like that in the beginning, yet she acted like it was so obvious. It wasn’t obvious. I didn’t understand at all.

I remember being embarrassed about how loudly I was crying. I knew I was embarrassing my dad, but I couldn’t turn off my feelings of injustice and confusion.

In the shot where Forrest is running with the football into the tunnel, and you can hear him breathing and the background blurs, and he says: “Now, maybe it was just me, but college was very confusing times,” he is describing my entire life.

I could just as easily say: “Life is very confusing times.”

There are so many things I can’t understand, yet everyone else seems to get intuitively. I often feel like I’m running somewhere, confused, not knowing what’s going on around me, or what the rules are, what I’m supposed to be doing, and why.

#6: He doesn’t understand (or expect) racism at all.

One thing I don’t understand at all—probably because I wasn’t raised in the South—is racial tension between white and black Americans.

I don’t remember seeing a single example of overt racism when I was growing up in California, nor when we moved to Colorado in my teens.

Sometimes, I’ve heard people make racial jokes, and they expect me to laugh at them and think they’re funny. But 90% of the time, I can’t even understand the context needed to even understand why the joke should be funny.

When I was in middle school, my church’s youth choir went on a “choir tour.” A boy I knew shared a joke with me that he thought was hilarious:

Question: “What did the Mexican boy get for Christmas?”

Answer: “Your bike!”

He told me this, and laughed hysterically. I mulled it over.

“Your bike?” Does he mean “my bike?” How would a Mexican kid get my bike? That doesn’t even make sense. I don’t even know any Mexicans.

I wasn’t sure what to make of it… I decided to laugh because it must have been funny somehow. I gave a courtesy chuckle, and he smiled and seemed really pleased.

“Your bike?” I kept wondering. “What could that mean? No matter how I approached it, it didn’t make sense. But with as funny as he seemed to think it was, it seemed that it must be funny but that I just didn’t get it.

I decided to try it out myself and see how people responded to it. When I passed some girls (who were older than me) in the hall later that night, I repeated what I’d heard.

Question: “What did the Mexican boy get for Christmas?”

Answer: “Your bike!”

“Ronny! That is AWFUL!” one girl told me.

Oh no!

What had I done? I felt sick to my stomach.

It was awful? How? I didn’t understand: when the boy said it to me, he thought it was one of the funniest things he’d ever heard. But when I repeated it, it seemed like I’d done something horrible.

But what?

Nobody would explain it to me. The girls just told me “I should know better.”

Growing up on the west coast, I didn’t know or understand anything about segregation, Confederates, the KKK, or white supremacy until I was at least 15 or 16. I still couldn’t even understand or comprehend what that was about.

The first time someone told me about the “Ku Klux Klan,” I was certain he was lying to me in order to make me feel stupid. I was 100% sure he made up gibberish words just to fool me.

The whole premise was wacky: people got together to create clubs based on their race and… say good things about their own skin color, and say bad things about different skin colors? What? That doesn’t make any sense at all. Why would people do that?

I hadn’t heard the term “redlining” until I was 35 when someone from Pennsylvania explained it to me. I had to ask him to explain it two or three times because I still couldn’t understand it (and can still barely believe it, and still don’t understand it).

So, I like that Forrest can’t understand what the KKK was about (even though he says he’s literally named after Nathan Bedford Forrest, who apparently started the KKK).

I also like that he goes to the Selma High School and interrupts the infamous scene of the first black kids going to high school, as George Wallace blocks the door, and National Guardsmen stand by. (Now, this event, I had read about in history books.)

To Forrest, it’s just another day in his life, and he has no idea what the cameras are there for, or what people could possibly have a problem with.

To this day, I don’t understand almost anything about the Deep South and racial strife: I’ve never been in any context where I would, really. It really seems fake to me.

It’s like when I heard that Easter Island was a real place. Was it? Is it? I don’t know… I think it is, but I’ve never been there, so I can’t be sure. It may still be a great big practical joke, or it may be real. I’m not sure.

My favorite part of the racial element of the movie, though, is where Forrest joins the church choir and finds himself as the only white person in the room (and in the whole church, it seems). Does he know he’s the only white boy in the room? Does he care?

Probably not, and what does it even matter?

This scene feels personal to me: many times I have found myself as one of a few or the only “white person” in a room full of people who don’t look like me. Often, this is in the context of church (and rightfully so).

When I visit the Caribbean, I like to visit churches on Sunday mornings. I am often the only white person in the audience, and that’s fine. I sing along with the loud Afro-Cuban music and have a great time and feel welcomed.

When I was a volunteer at an ESL school, I was sometimes the only white person in the classroom, and that was fine, too. Sometimes I like to visit Roman Catholic churches in Arizona (where I live) and I’m often the only non-Hispanic person I see there.

When I was growing up, a lot of my friends were children of Indian, Chinese, or Japanese immigrants. I barely noticed this, except that if I spent a lot of days in a row with my Indian friends, I’d sometimes laugh when I looked at myself in the mirror because I seemed so white compared to them.

I have never understood why some people are obsessed with race, and I don’t even fully understand the concept of race. Neither does Forrest. He looks at people equally and treats them all the same, and doesn’t understand why anyone else would do otherwise. “That’s good,” as he would say.

#7: He’s not impressed with hierarchy or social status.

Meeting the president becomes boring

What’s the best part about meeting the President of the United States? To Forrest, it’s just the food. That’s about it.

“Now, the real good thing about meeting the President of the United States is the food. They put you in this little room with just about anything you'd want to eat or drink. ...I musta drank me about fifteen Dr. Peppers.”

The first time he meets the president, he thinks it’s kinda cool. The second time, it’s still kinda cool. The third time, he’s annoyed by it, and he rolls his eyes as he explains.

“...a few months later, they invited me and the ping-pong team to visit the White House. So I went again. And I met the President of the United States again.”

Understanding how social hierarchies work, in the first place, is hard enough for people with autism. And, eventually, it just becomes tiresome.

Why is this guy so special? Who says? Who cares?

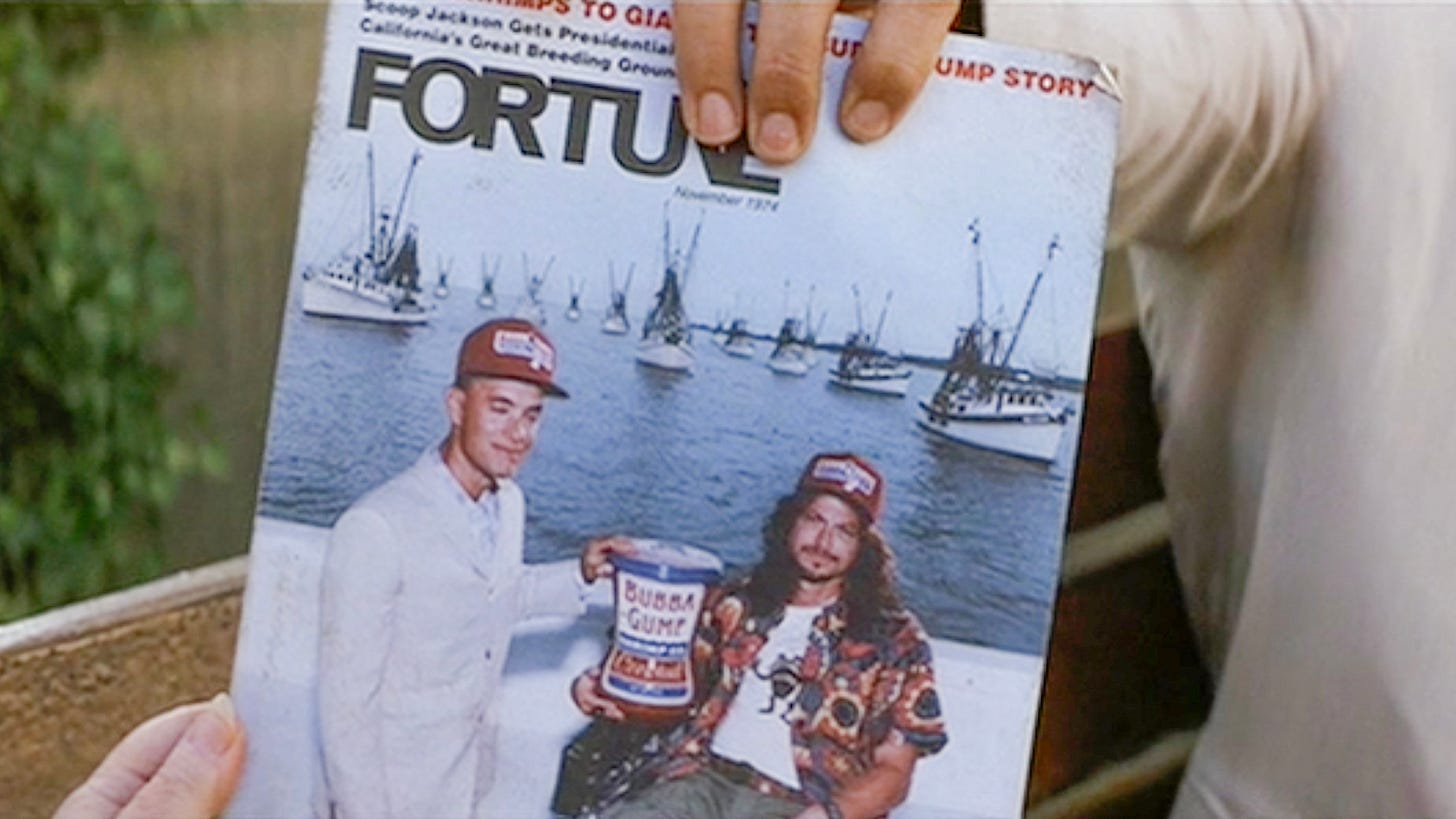

He isn’t even impressed with his own achievements

One of the strangest parts of the movie is how Forrest is exceptionally lucky and/or talented and succeeds at almost everything he does. Think about it:

He’s awarded the Medal of Honor, the highest military decoration in the USA.

He’s a national champion football player.

He’s a world-champion ping-pong player.

He gets rich by investing in Apple stock.

He runs across America from ocean to ocean multiple times.

He becomes an even richer man by starting a successful shrimp company.

He makes the cover of Fortune magazine.

He meets John Lennon, Elvis Presley, and three American presidents.

By every measure except his I.Q., Forrest is phenomenally successful.

Yet he’s just a normal dude sitting on a park bench wearing dirty running shoes and sneaking some of the chocolates he’s about to give Jenny as a present.

He’s almost boring people with the stories he tells about his impossibly-exciting life.

At one point, he even says: “And ‘cause I was a gozillionaire and I liked doing it so much, I cut that grass for free.” He mowed the lawn of his college football stadium for free because he had nothing better to do with his time and didn’t need more money.

He doesn’t care if people believe him or not

The woman on the bus bench listened to Forrest’s tales, and never challenged him. But the man sitting next to him eventually decides Forrest has gone too far and has been lying this whole time and calls him out.

Man: “Hold on there, boy. Are you telling me you're the owner of the Bubba-Gump Shrimp Corporation?”

Forrest: “Yes, sir. We've got more money than Davy Crockett.”

Man: “Boy, I've heard some whoppers in my time, but that tops them all. We was sitting next to a millionaire!”

Forrest isn’t phased by this insult at all. He just keeps talking to the woman still sitting there as if what the man just said didn’t even bother him.

When he shows the woman the magazine cover, she’s completely incredulous. She realizes this man—who she thought was just a bumbling idiot making up tall tales—is the real deal and has been telling the truth.

But he doesn’t even care about convincing her. He just tells her his story, and assumes she’s believed him this whole time. He doesn’t even notice that she didn’t.

Autistic people are like this sometimes.

Success is reward enough, whatever that looks like. It’s not about money, or accolades, or impressing others. It’s just nice to be able to accomplish what you set out to do.

He never intended on getting rich, or earning a single one of his decorations and awards. They just happened because he was doing the steady, boring work of putting one foot in front of another.

#8: He has the faith of a child.

Forrest goes to church. He prays. He sings in the choir. Even when people bully him about his beliefs, he remains strong.

On the shrimping boat, when Lt. Dan is trying out his “sea legs,” they’re unable to find the shrimp that they want. First, he says to Forrest: “maybe you should just pray for shrimp.”

Forrest does, and they still don’t catch any shrimp, so Lt. Dan bullies him: “Where the hell’s this God of yours?” But Forrest ignores this.

He keeps going to church… he even brings Lt. Dan with him sometimes. His faith is unwavering in spite of the sarcasm and hostility from his first mate.

Eventually, Lt. Dan gets over his anger, has a change of heart and, Forrest suspects, he “made his peace with God.”

Being able to ignore bullies is one of my superpowers: like Forrest, for the most part, I just disregard the haters in my life and those who make fun of me, especially regarding my faith.

When people make fun of Forrest and his beliefs, he just ignores them. Me too.

#9: He has almost no friends.

There are many people in his life, but almost zero people he could consider friends. Aside from his Momma, who loves him unconditionally, most people in his life, as I mentioned before, treat him horribly.

Bubba is really the only one who could be considered a solid “friend,” from start to finish, but he dies in battle within a few months of meeting Forrest.

Jenny is kind of a friend, but she’s an awful friend. She pops in and out of his life at random intervals, takes advantage of his good will, and never seems to actually care about how he’s doing or what he’s up to.

She also leads him on romantically (she tells him, “I’ll always be your girl”). Only in the very end does she really act like his friend, right before she dies.

Lt. Dan eventually becomes his friend and business partner, but only after a long season of being a wandering, dysfunctional alcoholic who is an insufferable asshole. He’s almost completely burnt out and is no fun to be around (they have an awful New Year’s Eve party that is utterly depressing and miserable).

Most people don’t know Forrest at all. They don’t care to know him. They don’t want to be his friend. They don’t necessarily hate him, but they’re just indifferent to him. They don’t see any value in befriending him, even though he has a life of tremendous achievement and is actually a fascinating person.

I feel like I understand this too well: I think most people I meet in life size me up right away and think something like: “Okay, so that’s who Ron is,” then move on and never think about me again. Or if they do, they think I’m quiet, arrogant, or boring.

But here’s the weird thing: I’M AN INTERESTING PERSON! I have done a TON of cool shit in my life.

I run my own business, I’ve been an opera singer, I’ve been laid off from three separate companies in three different industries, I’ve gone bankrupt, I have five kids, I’m a scuba diver, I play five different musical instruments, I used to have a dozen pet snakes, I used to breed lizards, I have a college degree in Storytelling…

I’ve run 5ks, tried flamenco, tap dancing, fencing, wrestling, ice hockey, rock climbing, whitewater canoeing, archery, blow guns, gymnastics, bodybuilding, sea kayaking, golf, and falconry…

I’ve studied four languages, I was an EMT, I’m a public speaker and writer with articles published in major national magazines…

I’ve met cool people like astronauts, mimes, senators, governors, congress members, mayors, city council members, and even four-star military generals…

If I sat on a park bench and talked to the people next to me, I could also regale people with amazing stories of people I’ve met, places I’ve been, and things I’ve done.

But they’d probably just say: “Huh. Ain’t that somethin’?” then move on.

There are very few people in this world that I can call “friend,” or who call me “friend.” I’m not exactly upset about that, but sure it is confusing. Why do other people seem to have so many friends? I don’t know what to do about it.

#10: He doesn’t understand self-harm or destructive behavior.

Jenny’s actions are baffling to him

After he retrieves her from a topless bar where men were throwing drinks on her and insulting her, Jenny stands on a bridge looking out at the water. She leans over the edge and says: “You think I can fly off this bridge?”

He immediately becomes upset and suspiciously asks: “What do you mean, Jenny?”

He knows what she means but can’t understand why she would even suggest this. She just gets mad at him and tells him: “You can't keep tryin' to rescue me all the time.”

He is confused and says: “I can't help it. I love you.” She gives him an extremely harsh response: “Forrest, you don't know what love is.”

Of course, the irony here is that Jenny doesn’t know what love is.

Forrest has done a better job of loving her than anyone else in her life: better than her father (who, it is implied, sexually molested her) and the long string of boyfriends who constantly abused her and pushed her into a lifestyle of nearly suicidal drug use.

When I was growing up, I met many young women like this. They exhibited all kinds of destructive behavior that made no sense to me whatsoever.

They smoked pot. They cut their wrists. They got drunk. They had eating disorders. They engaged in sexual acts with boys. They stayed with and around boys and men who were abusive to them.

One girl I knew even tried to kill herself when some idiot she was obsessed with refused to date her. Why?

I do not, and never will, understand this. Neither does Forrest. But he’s still there, chasing Jenny, following her, protecting her, and rescuing her, even when she doesn’t want him to.

He’s confused about her relationships with bad guys

Multiple times, Jenny is dating abusive boyfriends, and Forrest watches with confusion and concern, and gets involved whenever he can.

One time, when he goes to visit her at her college, she pulls into the parking lot with a boy—Billy—and starts making out in the car (we guess—we can’t see through the foggy windows). Jenny can be clearly heard saying: “Ouch! That hurts.”

Forrest runs up to the car, opens the door, and starts punching Billy in the face. Jenny gets out of the car, goes around to the driver's side door, and shouts at Forrest to stop.

“He was hurtin’ you,” Forrest says.

Jenny, very confusingly, says, “No, he’s not!” More shouting ensues, and Billy drives off while Jenny is begging him not to leave.

This is exceptionally confusing to Forrest, me, and (I think) anyone else with autism.

Jenny LITERALLY said out loud that Billy was hurting her. So Forrest got involved. Then Jenny acted surprised and asked Forrest why he was doing what he was doing. He says it’s because she’s being hurt, and she says that’s not the case.

What? Billy was hurting her. She said so with her own mouth.

Maybe he wasn’t hurting Jenny in exactly the way Forrest thought, but he was still right. Yet Jenny is mad at Forrest! WHAT?!

Why do some women do this? It’s very, very hard to understand.

In a more violent scene, Wesley, another boyfriend, a member of some quasi-communist movement, literally slaps her in the face so hard she falls to the ground.

Forrest gets involved again, running up to the man and beating the crap out of him.

Once again, Jenny runs up to Forrest and tries to stop him. “Forrest! Quit it! Quit it! Forrest! Stop it!” she shouts, pulling him off the other man.

Eventually, both Forrest and Jenny get kicked out of the Blank Panther headquarters.

The next day, Wesley says the strangest thing to Jenny right in front of Forrest.

“Jenny, things got a little out of hand. It’s just this war and that… that lyin’ son-of-a-b*tch Johnson. I would never hurt you. You know that.”

It’s totally surreal to see this awful man—who literally hurt her—say that he would never hurt her.

And it’s made even more ironic by the fact that Forrest told her “I would never hurt you” the night before. Except Forrest meant it, but Wesley didn’t.

Once again, I don’t think I’ll ever be able to understand abuse (physical, sexual, or otherwise). It doesn’t make sense to me, and it doesn’t make sense to Forrest.

…and most of all, it doesn’t make sense why Jenny keeps running after these men who treat her so poorly, while running away from Forrest, who treats her so well.

In the end, whether Forrest Gump is or was a real person or not, or is or was someone with autism doesn’t matter much. What matters is that this movie shows autistic traits on the screen better than almost anything else I’ve seen.

If you know someone with autism, please try hard to understand. We’re not stupid. We’re not jerks. We’re not boring. We have challenges just like everybody else. They just may be different challenges than what everybody else seems to have.

Finally, please remember (or learn for the first time) that autism is a “disorder.” It’s not a disease. It’s not a deformity, and it’s not necessarily even a disability. It depends on each individual person.

Autism is something that just makes people “different.” And, as Momma Gump asks: “What does normal mean, anyway?”

Precisely.

Loved reading your thoughts about this. I will always remember how much you loved that movie. I haven't seen it in many years, I'll have to watch it again but I remember a lot of it.