I Invited a Mime Over for Dinner. He Couldn’t Stop Talking.

If you could invite a mime over for dinner, what would you ask him? What do you think he would say? Would he even answer you?

I had the opportunity to spend an evening with a real, live, professional mime back in 2018, and I still think about our conversation all the time. Because, as I quickly learned, this man, who’s made an entire career out of performing without speaking… had quite a bit to say.

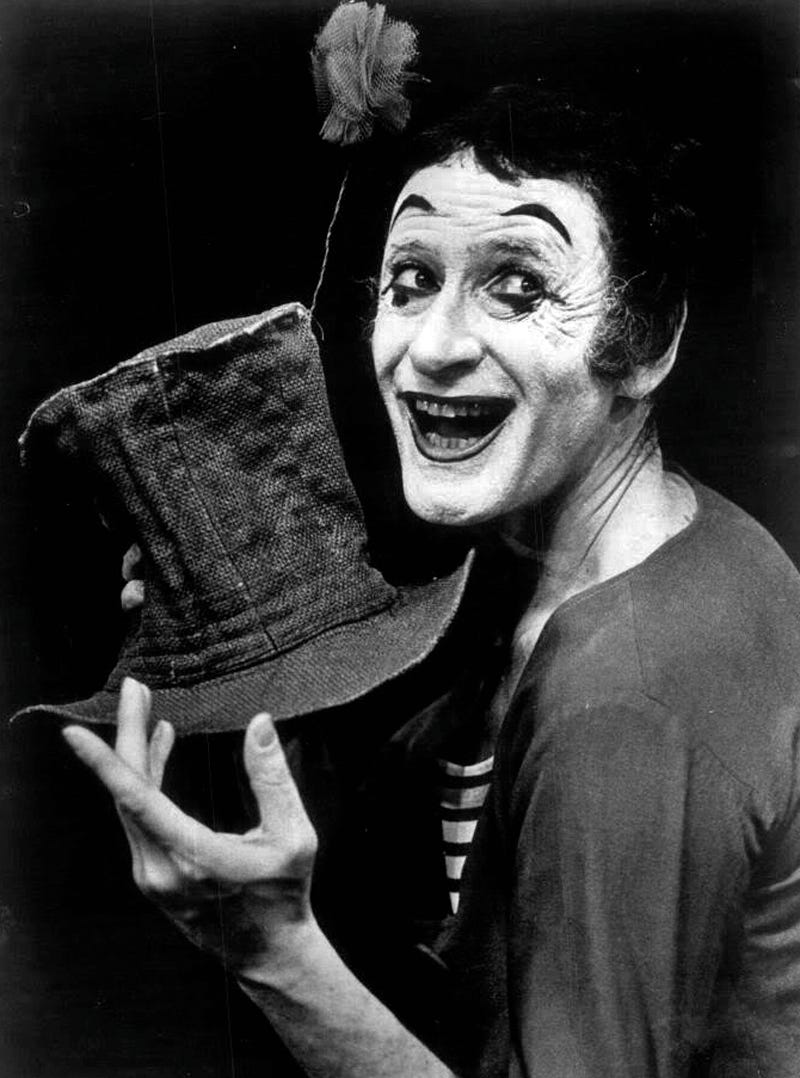

For context, Samuel Avital, director of Le Centre du Silence Mime School in Boulder, Colorado, is a professional mime. As a young man, he lived in Paris, studying directly with legendary teachers of movement, acting, poetry, and mime, including Étienne Decroux, Jean-Louis Barrault, Jacques Lecoq, and Marcel Marceau.

But those are basic facts that anybody could read about on his website or Wikipedia page.

What you would never learn by just reading about him on the internet are the things I learned when I met him. Things like:

He just turned 92 years old.

He’s an extremely short man.

He’s very, very, very opinionated.

He constantly vacillates between being very serious and very silly.

He loves to say, “Ooh, la, la!”

When my wife was a student at CU Boulder, she signed up for an independent study course with Samuel as her teacher in order to complete her BFA (Bachelor of Fine Arts) in Dance.

For weeks, she would come home from her private mime lessons at Samuel’s house and regale me with the craziest stories about this tiny little man with a gigantic personality and all the bizarre things he made her do during her studies.

They would have deep discussions about spontaneity, masks, dreams, isolation, undulation, truth, lies, illusions, and many other concepts that people without a “grammar of movement” would find mystifying and overwhelming.

The image I had of him over the semester was so ridiculous that I asked her at one point, “Am I ever going to meet this guy?” She suggested we invite him over for dinner to meet the whole family, so we did.

Samuel doesn’t drive, so I went to pick him up from where he lived in Boulder, and drove him back to our house in Longmont, about 20 minutes away. From the very first moment I met him, I was impressed, not just with his movement, but with his mind and being.

He had a razor-sharp wit, and it was clear that he had plumbed the depths of the biggest questions mankind has pondered for millennia. As a lifelong student of philosophy, theology, reality, and existence myself, I was immediately intrigued.

We dove into a deep conversation about movement, being, thought, and the meaning of life as I drove with him in my passenger seat. On my way to Samuel’s apartment, I stopped by a pet store to pick up feeder crickets for my Mexican Alligator Lizards, and they chirped the entire drive back, providing a surreal and poetic backdrop to our conversation, to his great amusement.

When we arrived at my house, Samuel and I got out of the car and walked inside. I introduced him to our five kids, and he mesmerized them by playing a game where he pretended that when they shook his hand, it actually hurt him greatly.

Feigning serious pain at the tremendous hand strength of my 5-year-old son, he broke the ice by making the kids laugh right away. Continually putting out his hand to be shaken then pulling it back instantly while yelping, “OUCH!” which confused and delighted them.

“Is he serious?” my youngest son’s face seemed to say as he looked at me and giggled.

“I didn’t really hurt him, did I?”

Our dinner with a mime had now begun precisely as you might expect: with wonder and mystery.

What I did not expect, however, was how for a man who normally makes a living using only movement—not words—my new friend Samuel Avital turned out to be a surprisingly verbose dinner guest.

We had dinner, and our conversation was so normal that I don’t recall very much of it at all.

But afterward, the kids stayed at the dinner table playing with toys and drawing in their coloring books while Samuel and I moved to the living room, where I engaged him in an informal interview about art, movement, performance, and much more.

It turned out to be a discussion of such depth that I still think about it to this day, almost every single day.

Over coffee and apple pie (or Tarte aux Pommes, as he told me it’s called in French), we engaged in a spirited—sometimes heated—discussion and debated topics like artistic merit, art criticism, art interpretation, philosophy, Michael Jackson’s dance moves, what it was like living in Paris, existentialism, ratatouille, one-handed clapping, and how late-night show comedians are destroying America.

Samuel is a delightful man but is a somewhat slippery subject. Getting definitive answers out of him was like an intellectual wrestling match: I tried to pin him down and force him to define terms and commit to truth claims, which he was always reticent to do.

His answers were not exactly evasive but often seemed paradoxical.

In fact, “It is a paradox!” was one of his favorite answers.

On at least five separate occasions, “It is a paradox!” was his final answer to one of my direct questions. Yet, confusingly, later in our chat, he also claimed—no, shouted: “A paradox doesn’t exist in my world!”

Samuel was an amazing guest and a serious rhetorical sparring partner. He challenged just about all of my assumptions about art and performance and made me think for many years afterward.

I’ve rarely been intimidated during a debate or discussion in my life. I was almost intimidated talking with Samuel, but I don’t think that was his intention. I believe that as a lifelong student and teacher himself, he wanted to give me something to think about.

He gave me some homework, so to speak.

It’s been six years since I met him, and I’m still thinking about our discussion and trying to decide how I’d answer him now if we spoke again.

There’s no possible way I can write out our entire chat, so I’ll just provide some excerpts on a few topics.

Important Note: Samuel was born in Morocco and speaks fluent English but has a thick Middle Eastern accent. He sometimes repeats himself, mixes tenses, or puts words in a different order than native-English speakers, which can be confusing. For clarity, I have lightly edited his responses to my questions so they read more naturally to Americans like myself.

Ron Stauffer:

What is it like being a mime? What do people think of your performances?

Samuel Avital:

Mime puzzles. It puzzles people, mainly.

But when I perform it, I try to make it simple. And you can understand on your level, wherever you are. You can understand. I have to present serious things comically. That is difficult.

In other words, I have to make it easy so the audience will understand it, right?

And so I discovered how to make that which is complex simple, and to make that which is simple complex. When you do that, the audience understands you, especially when you don’t say a word.

If you say a word, you can explain it to them. I can explain to them about the beauty of the sun or the majesty of the mountain. But that’s words. So poetry is cheating.

Ron Stauffer:

Do people sometimes ask you to explain things?

Samuel Avital:

Oh, I have had enough of explaining to students. That’s enough! I stopped explaining.

Ron Stauffer:

But people do ask you to explain it, right? And you just say…

Samuel Avital:

Oh yeah, yeah. I say, “I am not a teacher to explain.”

Because to explain is a plane. It’s linear. It’s like playing the violin with one hand. Could you play the violin with one hand? No, you can’t. Using only the left brain?

Could you clap with one hand? No, you need two hands to clap.

Ron Stauffer:

Do you ever take requests when you’re performing? For musicians, people in the audience will say, “Hey, play Free Bird!”

Samuel Avital:

No, no, I don’t let them do that. I don’t need to prove myself. There is a time and a place where to do that. Music, I think is more... they will say “encore,” but... it’s a different art.

Ron Stauffer:

Do people understand mime? Do they understand what you do?

Samuel Avital:

When people say, “I understand,” I know they don’t understand. Why? Because their understanding is linear, and linear thinking is limited.

Musicians, clowns, theater people… you have to be creative, and you have to use the right side of the brain… the right hemisphere.

So, for somebody to say, “I understand…” they understand intellectually.

Ron Stauffer:

Okay, so how can they understand “the right way?”

Samuel Avital:

They have to awaken the right side of the brain—the creative side. Most people are not creative. They live half-lives.

If you want to learn, you have to be in a receptive state to receive what I give you. Not just with words. I can tell you this with words, but you have to take the initiative to do it... to experience it.

After that… what you do with it? That’s not my business.

If you are a dedicated person, you will practice it until you master it, and use it... and give it. Otherwise, you get constipation, artistic constipation, if you don’t give what you know.

Ron Stauffer:

But if what you do is something where you don’t offer an explanation...

Samuel Avital:

No. You experience it. I don’t explain to people what to do. It is unconventional learning.

Ron Stauffer:

So, when you give a performance, does it have a definite meaning that people either get or don’t get?

Samuel Avital:

They should get it. Because I strip the talking about it, and I go to doing it or being it, and you understand.

Ron Stauffer:

So if 18 people come to see your show, and they walk away thinking that it’s about 18 different things, is that good, and is that your intention? Or is it that they don’t understand it?

Samuel Avital:

What they receive is not my business, but they could interpret it in different ways.

Like once, I had a performance being an insect at La MaMa in New York. After I finished the show, there’s three people entering my makeup room and looking at me.

And I noticed, so I say, “Why do you look at me like that?” He says, “We want to check if you are a little animal or human being.”

I say, “Why? You must be Psychiatrists.” (Yes, they were Psychiatrists).

He says, “Well, when we saw you in this piece—the insect—you blurred the human and animal difference. Once we think you are animal, once we think you are human.”

I say, “I want to humanize the animal.”

And the other one says, “Well, we saw that you animalized the human.”

I say, “Yeah, that’s true too!”

So they have their interpretation.

Ron Stauffer:

You’re probably going to say, ‘Don’t do this,’ but I’m trying to think of a parallel. Like, if you see a Jackson Pollock painting or Georges Seurat or someone like that... If 50 people look at it, then maybe they see 50 different things. I don’t know whether that’s good or not. Is that okay?

Samuel Avital:

That’s the genius of the artist!

Ron Stauffer:

Is it the same for you?

Samuel Avital:

You know, I give you another example. The painter does his work, and puts it in the gallery. And people come and look and they ask the artist to explain.

That’s an insult!

He says, “I already did my work! It’s up to you to understand the way you want to.”

That’s the freedom of intelligence. You don’t insult the intelligence of the artist!

Ron Stauffer:

But if you don’t understand it, whose fault is it? Is it the fault of the artist?

Samuel Avital:

No fault! There’s no fault!

Ron Stauffer:

But who is misunderstanding?

Samuel Avital:

The dumb one! The dumb one!

The “intellectual” will misunderstand it. The academician will misunderstand it.

The painter puts his painting on the wall, and that’s it! He’s done his job. The rest is up to you.

Ron Stauffer:

So if someone in a museum looks at a painting and asks for an explanation…

Samuel Avital:

That’s an insult!

That’s what theater critics and art critics do. Most theater critics and art critics are failed artists. That’s why they become critics, right?

Could you explain to your eyes how to see? Could the eye see itself? Come on! The eye sees itself?! The eye is the instrument of seeing. It does its work. You don’t interfere. If you interfere, you will be blind.

That’s what academicians do. Academicians, lawyers, politicians, philosophers, you know, experts; all the “crème de la crème” of supposed intelligence in humanity.

Ron Stauffer:

So, what would you tell somebody who is struggling to understand that concept? Someone who asks, “What is this?”

Samuel Avital:

I don’t accept that one as a student! I tell my students, “You are not here to understand. Okay? You are not here to understand. You are here to become, to be.”

And that’s the most difficult thing. Some like it… it’s intense because the ego doesn’t let them interfere. You have to send the ego to vacation (laughs).

Ron Stauffer:

What if a man likes a painting but doesn’t understand it exactly? Should he still support it? Should he buy a painting at a gallery if he doesn’t get it?

Samuel Avital:

There’s no support of the arts. For the artist to be, an artist should not suffer, he should be free to express himself. And if you don’t understand him, you should give him more money so he wouldn’t worry about it and do something genius.

But the genuine artist doesn’t give a damn about your money.

The good artist doesn’t give a damn if he doesn’t eat two, three days to finish his art to try to understand himself.

As an artist, I try to understand myself, the universe, how I function… it’s another end. Do you know?

Ron Stauffer:

Sure. On a separate note, what’s the purpose of the neutral mask? (Note: a “neutral mask” is a mask worn by a mime that is cast of the performer’s own face in a “neutral” position: not smiling and not frowning.)

Samuel Avital:

To discover and make the body more expressive.

Ron Stauffer:

And how does that work? I watched Rachel make her own neutral mask, but I haven’t seen her perform with it or anything yet.

Samuel Avital:

When she covers the face, okay, there is an increase of physical expression. How? You have to see it; I can’t explain it… when your face is open, you are restricted in your movements.

Ron Stauffer:

Really, how?

Samuel Avital:

What do you mean, how? The body is restricted because you know you are being watched!

When you cover the face, the movement is expressed very good. You discover how the body expresses itself better than when you are open with the eyes and things exposed.

Ron Stauffer:

And is that because… you feel like you’re hiding?

Samuel Avital:

It’s psychological… you think that you are hiding yourself, but you’re not.

Video Excerpt: “Black & White” (Full Version on YouTube)

Ron Stauffer:

What is it like to have people laugh at you every single day?

Samuel Avital:

I make people laugh all the time, every day, with everyone I meet. I don’t attack them. I present things as they are. And I confront them in a certain way, you know, and they realize… it triggers something.

Like, for instance, many people think they know how to think, right?

No! The process of thinking is a very important process.

Think about it: what is a thought?

Ron Stauffer:

What is a thought?

Samuel Avital:

I ask kids sometimes like that: “What were you before you were born?” And some kids… this happens many times…

Some friends of mine. I always ask them: “Are they for sale?” you know, their children? They laugh.

Once I was on the street, we stopped all of them—this group of parents that day and this girl, she’s beautiful. She’s six or seven. I ask her: “What were you before you were born?”

She didn’t hesitate. She says, “I was a thought.”

And that’s the truth!

She was a thought in the mind of the mother and father… and from the thought, she became.

And the parents didn’t know what to do with this. But she answered immediately.

It’s the truth! She was a thought! Immediately. No hesitation.

And a lot of people will hesitate.

Even if you ask my own students: “What were you before you were born?” They will begin to intellectualize with me, to write five volumes of words, and blah blah blah…

You can see that, right?

So what is a thought?

I do this on stage. I try to chase my thought around like a fly. (Here, he mimes grabbing a tiny thought floating around above his head).

It’s just a whole thing… five minutes. Crazy!

I try to catch a thought!

“Where is my thought?” and I begin with that. I start like “Le Penseur,” the statue from Rodin.

I awaken, and the thinker begins to see.

“Where is my thought?”

It’s really just… it’s almost frightening. But it’s sincere. They know—the audience—they know I’m trying to catch a thought.

But I can’t catch it!

Oh, now I get frightened! Now, it’s in my hand! Then I try to eat it!

Now I think, “Am I a thought?”

But when you explore that artistically speaking, it’s funny.

And some people look at me and think, “This guy’s stupid.” No. He is not stupid. He’s doing something; he is saying something.

Here’s another example: I call it “My World.”

I come on stage and I knock on different doors. Nobody opens them. Until I realize that a door has to have a key, but I didn’t have patience for the key. So I just broke the doors.

And I go to all different kinds of doors, you know: revolving doors, big doors, small doors, more doors, until I come to a little door like that (he mimes a tiny door) and I have to crawl inside… that’s where I discover the treasure.

So I discovered inside the… what do you call it? Trunk? Treasure chest. I open it. I find another one. I find another one inside it. I find a little one.

I open it. I find a little balloon (here he mimics inflating a balloon).

I go inside the balloon, and I wave “bye-bye” to the audience. That’s how I begin the show.

You could understand it any way you want. But it is very entertaining because… you don’t understand if this guy is crazy or a genius.

But it’s simple. It’s difficult to do simple things on stage, right?

Ron Stauffer:

Yeah, yeah, definitely.

Samuel Avital:

A simple musical note. It’s the most difficult to do.

Ron Stauffer:

Most difficult to do well, certainly.

Samuel Avital:

To do well, correct. Because the people who know… they can know when you make a mistake or not, musically speaking, if you know your text… and solfege and all that, right?

Any genuine artists—which are very rare now, not only in America but in the world…

There is what I call “the minimization of being,” you know, when the calculator begins to come here, right?

Ron Stauffer:

The calculator?

Samuel Avital:

Yes, calculators: they shut off one area of the brain—to calculate; calculus. Now you do it (he mimes using a calculator for a math problem), and you pass the exam.

But you don’t do it. It’s not you. It’s the machine that does; it’s not you.

Where are you?

That area in the brain now… is technology. That’s what I say.

I keep saying to my students: they give you this great illusion that technology is advancing the world.

I think it’s retarding the world now, especially now with artificial intelligence, and they call it “artificial superintelligence.”

Now the ethics are slipping away, so it retards you. You use less of your brain.

Is that good?

Ron Stauffer:

No, that’s not good.

Samuel Avital:

It doesn’t take an ounce of human.

Machines are going to tell us what to do now. What to decide even.

Our conversation was much, much longer than this, but there are some thoughts and memories I’d like to keep to myself.

Toward the end of the evening, we kept talking, and I took the feeder crickets I had bought and dumped them into the tank where I keep my Alligator Lizards.

We stood there, eating blueberry and apple pie and watching the lizards chow down on their crickets. Samuel found his own book on our bookshelf and pulled it down.

I kept asking him questions as he flipped through the pages, looking for a specific concept he had written about many years ago that he wanted to share.

He then decided to turn the tables on me.

Samuel Avital:

So you are asking the questions, right? Now I’m going to ask you a question.

Ron Stauffer:

Okay, sure.

Samuel Avital:

Who is in you that asks the question?

Ron Stauffer:

Who is in me that asks the question?

Samuel Avital:

Yeah. Who is the asker? Do you think there is a question and there is an answer?

Ron Stauffer:

Uhh…. Say that again?

Samuel Avital:

Is there such a thing as a question? Is there such a thing as an answer?

Ron Stauffer:

I think so.

Samuel Avital:

I think no.

There is no such thing as a question and an answer. Those who are busy with questions and answers are not living.

They are speculating like the scientists. Speculating until another scientist will come along with another theory, and then one will come and repeat the thing, and repeat and repeat.

So what’s going on? What’s this game about? And I ask that question all the time.

“Who is in you that asks the question?”

For me, the real you knows everything. But you don't know that you know everything.

Because you're still asking, and you don't know who's asking. And even if you ask, you want an answer, but there is not such a thing.

It is a paradox, right?

Ron Stauffer:

It certainly is.

Samuel Avital:

But a paradox doesn't exist in my world!

It doesn’t because when you experience it, you experience the paradox. Therefore, there is no paradox.

Have you ever thought about these things? No!

Ron Stauffer:

It's funny that you say, “Don't call me a philosopher,” because you definitely are!

Later, he finally found the pages he was looking for in his book and started sharing quotes from world-famous geniuses in art, including people like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Martha Graham, Étienne Decroux, and Salvador Dalí, who — for all I know — he may very well have met in person and even worked with at some point.

When his ride came to pick him up, he stopped ruffling the pages, closed the book, and said, “This is a nice little book! Who wrote this book?” while laughing.

I also laughed at the unbelievable circumstance I found myself in: it was almost too much to believe.

I was in my office at my house in Colorado, discussing artificial intelligence, the meaning of paradoxes, and whether questions and answers even exist, with a tiny mime who was almost a century old and who was laughing at quotes from his own book on creative movement while we watched lizards feed on live, chirping crickets, as we ate pie and drank coffee.

It was hard to comprehend just how strange an evening this had been and just how chance this encounter was.

What a life I’ve lived, and what a fascinating person Samuel Avital is.