Earlier this summer, I got a completely unexpected phone call from my grandpa. He told me that he and my grandmother (“Grammy”) had decided to sell their house in the Colorado mountains and move into an assisted living community in a larger city nearby.

I was completely surprised by getting a call from Grandpa out of the blue, but what he said wasn’t so surprising in and of itself. My grandparents are getting up there in age: Grandpa is now 90, and Grammy is, well… actually, she’s the one who taught me never to ask about a woman’s age, so I’ll pretend I don’t know (even though I can do the math).

It makes sense, of course: living by themselves in a small mountain town on the top of a hill, where it’s a significant drive to or from anywhere, is not a permanent solution for aging folks.

At some point, mobility becomes a serious issue, as does safety. Just getting up the stairs is hard enough, but danger lurks as well: those TV commercials that show the elderly woman saying, “I’ve fallen, and I can’t get up” were hilarious to laugh at as a kid, but the prospect of being a frail and aging woman literally falling on the ground, unable to help yourself back up isn’t funny at all.

So it wasn’t a big shock to find out that as my grandparents get closer to a full century of living, they can’t do things like they used to anymore and needed to make a change. Especially since they’ve been living in a single-family, two-story home in the forest, where their closest relatives live over 30 miles away.

Also, the road up to their house from the highway is one of the steepest streets I’ve ever driven on, and I can’t imagine being 90 years old and trying to drive up a hill like that with inches of snow on the ground when it’s three degrees outside. That could be life-threatening.

But after I got off the phone with Grandpa, I was actually shocked by two things.

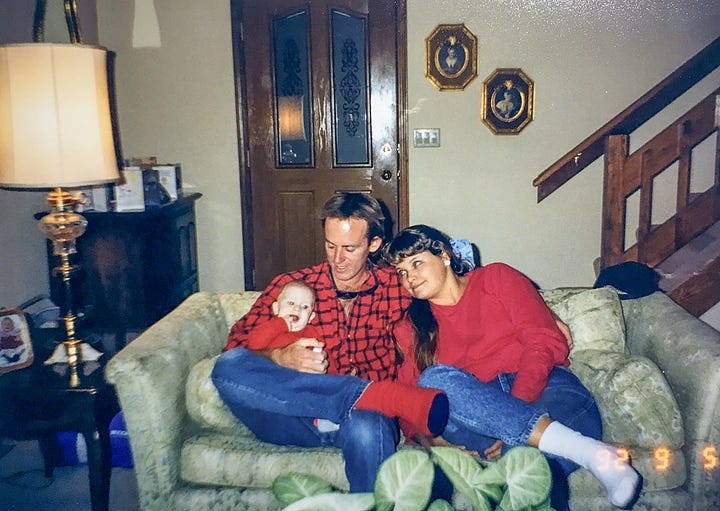

The first is the fact that they decided to sell the house at all. To be completely honest, I never saw that coming. Why would they sell their house? I always figured it was their forever home. They had it custom-built when they moved from California to Colorado back in 1990. (Wow. Just thinking about that blows my mind: that was almost 35 years ago!)

The second is how it made me sad. I mean, really sad. A few days after I heard the news, out of curiosity, I decided to check out the house on a real estate website. That may have been a mistake. Seeing pictures of their house for sale was really weird.

I’ve seen a lot of houses for sale over the years, and I’ve never once had an emotional response to seeing one before. But this was different, somehow. It wasn’t even my house, but as I clicked through the photo gallery and saw image after image of blank, empty rooms, I nearly cried.

Gone was all the art on the walls: the family portraits, the posters of the marathons Grammy had run in years ago, the old-fashioned wooden clocks, and Cousin Bucky’s watercolor painting. All of the dozens of incredible, detailed needlework pictures Grammy had carefully hand-stitched over the decades were missing, too.

The wall by the staircase going up to the bedrooms was always so covered in beautiful embroidered pictures of Hummel figurines, birds, butterflies, and angels that I almost didn’t even realize there was paint behind them until now.

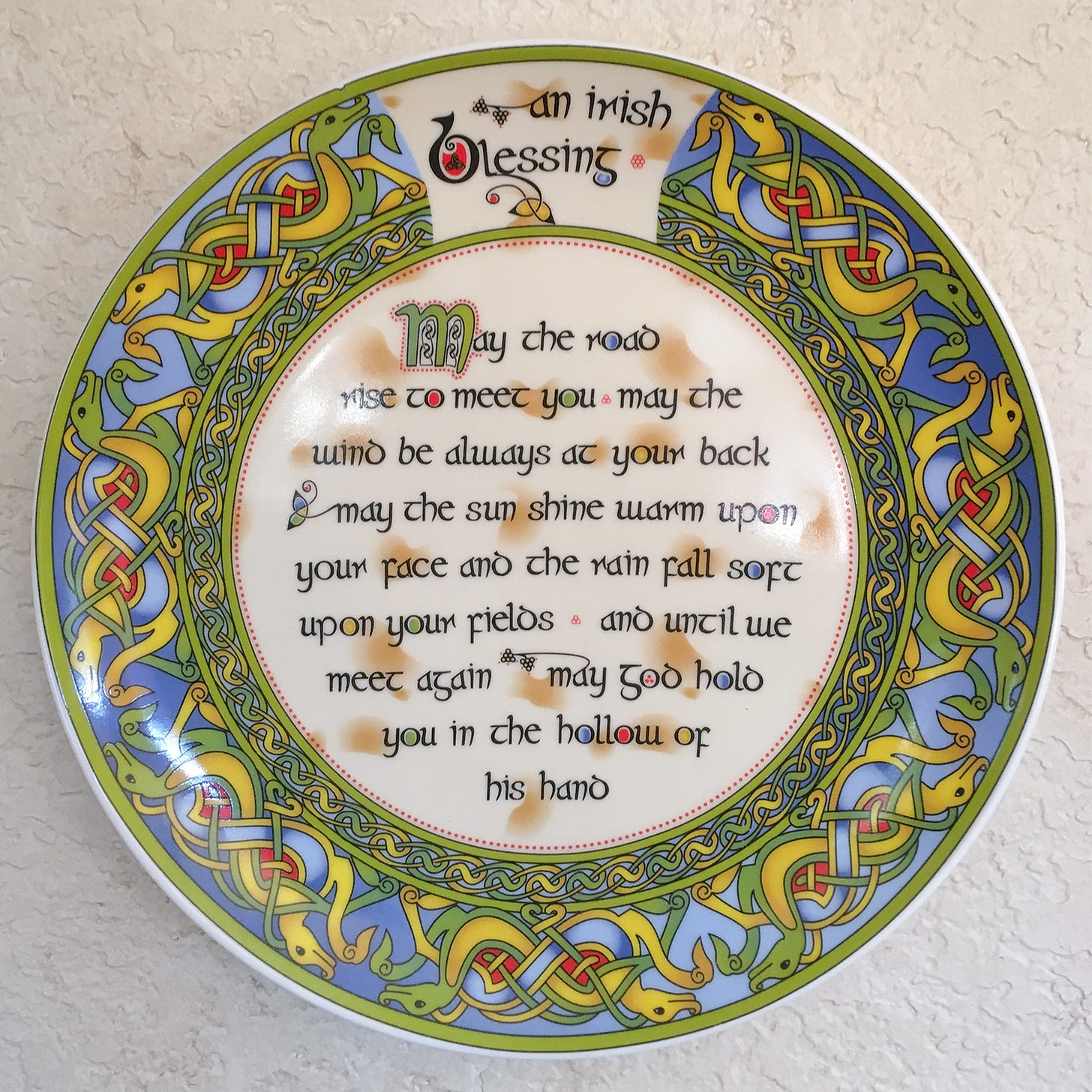

Looking at these pictures of a now-empty house, I can see the ugly, boring paint on the walls and ceiling, plain as day. It’s mostly just… white everywhere. The dining room hutch with the fine china is gone. The decorative plate on the wall with an Irish blessing is gone. The foyer cabinet in the front entry is gone as is the door mat that says: “A golfer and a normal person live here.”

There used to be pictures of me in that house. Now, even they’re all gone.

Everything is gone.

There is nothing left.

The house in the photos is totally empty, devoid of all human touch; it’s basically an abandoned house on a mountaintop. Looking at the sales data, I can tell that it took over three months to sell.

That means for about 100 days, the most important place in the Stauffer family—where many of the most memorable moments of my life happened—was a vacant house with a “for sale” sign out front. How could this happen? How could we let this happen?

Like a dead body rotting in the sun, all the life had gone out of this structure. It was now just a corpse on a cul-de-sac.

Looking at the listing, with one depressing click after another, I saw how the epicenter of my childhood for the past three decades has now become nothing more than an empty shell for sale to the highest bidder.

It feels almost grotesque.

Honestly, it’s hard for me to even comprehend: I feel like a rug has been pulled out from under me, and now I’ve fallen and can’t get up. But I don’t have a “Life Call” button for someone to come help me in my moment of need.

Thinking about this actually started to make me angry.

Why would my grandparents sell the house? Isn’t it a “family” house? Why wouldn’t one of my five uncles inherit it? Whatever happened to keeping things in the family and passing down property from one generation to the next?

I’ll admit that growing up, I always secretly wondered if I, as the first-born son of the first-born son of my grandparents, would inherit this house… or something kinda sorta like that. If Dad didn’t, I’d be next on the list. Right?

When you’re a kid, life is very simple and black and white that that. Why wouldn’t we do everything we can to keep our family property and our legacy?

Just think of farmers: why on earth would one generation sell the family farm before the next generation can take it over? And who could possibly imagine that parents would sell their farmhouse to an outsider rather than give it to their kids? At a bare minimum, why wouldn’t they at least give the kids the first right of refusal to buy it from them?

My grandparents’ house in Woodland Park is the closest thing we’ve ever had to having a “family farm,” at least in my lifetime. So, to watch it slip away from our fingers is just… unimaginable. It’s a sadness of historic proportions for me.

I learned a bit about a family’s legacy (or lack thereof) and what that means when I took a trip across the country a few years ago as a class project during college.

In 2019, I went to Pennsylvania to find my family’s first-generation immigrant ancestors. Both sides of my family (Irish and German) came to America by way of Pennsylvania, but I was mostly there to see the Irish side.

As I drove all over Northeastern Pennsylvania, I tried finding all the locations that had meaning to my family members. Armed with a list of historical addresses of the houses they lived in, I tried to methodically visit each one and check them off the list.

By doing so, though, I found out a few things that made me very, very sad.

First, most of the homes were dilapidated and in serious disrepair. It was clear that they had never been nice to begin with or hadn’t been in good shape for a very long time.

I shook my head in disbelief as I saw a rotting shotgun shack in an extremely dirty and dangerous neighborhood listed as Grammy’s childhood home in downtown Philly.

Litter was strewn everywhere, garbage was blowing all over the streets, and the roofs and gutters of some of the rowhouses nearby were falling off!

Second, some of the houses my family members were born in, lived in, and even died in didn’t even exist anymore. Some were literally missing: they had been torn down.

In some cases, newer, nicer homes stood in their place, sometimes with totally different street addresses. Sometimes, though, there was nothing in their place: just an empty lot covered in dead grass or concrete. It was just gone.

Third, not a single address for any house I could find was still in my family’s name. My kin had long since moved on. If I had knocked on any of the front doors of these houses, I might have been cursed at or threatened.

“But I have records showing my great-grandfather was born in this home!” didn’t feel like a very good defense for showing up to a stranger’s home uninvited in a state I’d never been to before.

In the end, I was glad I made this trip, but as I processed what I was seeing, an incredibly depressing reality set in: the only remaining traces of my family on the East Coast are the gravestones on the ground where my ancestors are buried.

But even this wasn’t entirely true.

I spent about an hour trying to find my Irish great-grandmother’s burial plot in Yeadon, just outside Philadelphia, only to discover that she didn’t even have a gravestone.

She was in an unmarked grave.

Where she had been laid to rest, there was nothing but bare grass, dirt, and what looked like deer droppings. I kicked away the droppings with my feet quietly but angrily.

When I got back home, I pondered all of this. The more I thought about it, the angrier I got: she died in 2000, which meant that for 19 years, nothing about the tiny plot where her urn of ashes was buried gave any indication that anyone had ever been there.

What was I to make of all this? What was the universe trying to tell me? That our family isn’t even worthy of being recognized by name after death?

My great-grandmother literally hadn’t even “left a mark upon this earth!”

What a strange, horrible thought.

I suppose, since our Irish family members were mostly blue-collar day laborers, who lived and worked in coal mining towns (and had very short lifespans), it might not be that surprising.

From what I can tell, the McElwees, Gradys, and Gallaghers were all poor, just barely trying to survive. Some were orphans, and there were alcoholics in the family.

With all that, plus their lifestyle and Irish culture in general, it’s not a shock that I didn’t find any “family farms” on that side of the family. And while I didn’t spend much time looking for any family property on the Stauffer side of the family (the German side), what little time I did spend researching them didn’t bring up anything major either.

This, actually, was very surprising. That the Mennonite side of our family didn’t still have lots of working farms filled with Stauffers was very strange. My Pennsylvania Dutch Faamilye—famous for being farmers who literally kept and worked on family farms for decades (or centuries, as in our case)—didn’t seem to have any property still owned by my family members now either.

How did this happen? Why did this happen?!

Abraham Stauffer, my fifth-great-grandfather, wrote about the Stauffer family farm in great detail in his last will and testament right before he died in 1860. How did we apparently lose it all in the 160 years between then and now?

The East Coast, of all places, is legendary for having some of America’s oldest and greatest intergenerational wealth. You can still see the vast, sprawling estates of families that have worked hard to create something glorious that still stands today and still carries the family name.

The Fords, Vanderbilts, Pulitzers, Du Ponts, Rockefellers, Rothschilds, Astors, and yes, even the Trumps, have streets, hospitals, buildings, colleges, hotels, and a lot more named after them… you can’t drive around America’s East Coast and not notice them. Their names are everywhere, and their legacy is undeniable.

So, what is my family’s legacy? What mark will we make upon this earth? What do I get to leave behind when I die?

Just another gravestone on the ground… if that?

For whatever reason, I always thought we didn’t have much, but at least we had Grammy and Grandpa’s house in the mountains. Now, we don’t even have that.

Or maybe we never had that at all, and I was reading way too much into it because I was just a kid with grandiose ideas, and I manufactured a narrative in my head that was completely ridiculous. I just don’t know.

So what now?

Now that our family is scattered across the four winds, and very few of us still live in Colorado, and we no longer have a central “anchor” to keep us all there anymore; what’s going to happen?

Will we ever have a Stauffer family reunion again? I doubt it. Where would it be?

The whole point of Grammy and Grandpa having (and keeping) that big, four-bedroom home for just two people was so we could host large family gatherings there. But now that that’s gone, what happens next? Where do we go from here?

I don’t know the answers to any of those questions.

I do know one thing, though: whoever those jerks are who just bought that special house in Woodland Park, they’ll have NO IDEA just how precious it is. They’ll probably look at it and think, “Well, it’s okay. But it needs work.”

They will probably paint over the walls where the embroidery used to hang. They will likely replace the carpet I used to race my Hot Wheels cars on. They may re-stain the back porch where we grilled so much bratwurst and drank so much beer. They might take down the giant chandeliers that lit so many dinners at the table in the living room where we drank sparkling cider out of wine glasses as kids and felt so grownup.

They won’t have any idea what happened in that house.

They won’t know about the life that was lived in that house.

They won’t know about the special things that made that house a home.

I had multiple birthday parties in that house, as Grammy, Grandpa and I all celebrated our birthdays together each August. (His on the 15th, hers on the 22nd, and mine on the 23rd).

I spent many holiday evenings during Thanksgiving and Christmas in that house.

I made love in that house when my wife and I stayed there during visits, sometimes bringing all our kids to come see “Gee Gee and Great Grandpa,” and sometimes going up there by ourselves to get away from the kids.

It’s hard to even understand all the memories made, the moments shared, the pictures taken, the food enjoyed, and the conversations had under that one roof.

The last time I went to that house, a few years ago, I spent the evening showing pictures of my Pennsylvania trip to my grandparents. Grandpa went to bed early, and I stayed up with Grammy, drinking wine, listening to stories of her childhood, and sharing the discoveries I had made on that trip late into the night.

It was a profound moment of family discovery. I told her about her mother’s missing gravestone and about the sad state of the row houses and the cemeteries in disrepair.

We laughed.

We cried.

We hugged.

The next day, I got in my car and drove away. I drove around in circles in the cul-de-sac, honking my horn and waving like Stauffers have always done for decades.

I said “goodbye” out loud and in my mind to both Grammy and Grandpa and to their house. But I didn’t know that would be the last time I’d see them there.

As of this writing, my grandparents are both still alive, and I’m very grateful for that. They’re living in a great retirement community with professionals who can help them 24/7.

But I’m also just immensely sad that their house still stands, yet if I drove by and pulled into the driveway and knocked on the front door, I’d be greeted by frightened strangers.

I’d feel like George Bailey in “It’s a Wonderful Life,” where he rings the doorbell of his family’s home and is greeted by a cranky old woman (his mother in another life) who just looks at him without any recognition and tells him to go away.

Grammy and Grandpa’s house is like that now. The home I spent so much time in growing up is no more. Well, actually, it is… but it’s complicated. If I show up unannounced, I’ll be as unwelcome as George Bailey visiting Ma Bailey’s Boarding House.

This is the case for almost every home from my childhood, actually. Every house I grew up in or made any memories in might as well be a boarding house today.

The first house I can remember in Stockton, California, has been sold at least five times since we moved away. (Also, someone decided to rip out the rosebushes and star jasmine vines in the front yard, which is sad.)

The second house in Stockton was a country house with a walnut grove in the backyard. It’s now so grown over with bushes that when I took a trip back to California last year and saw it, it was not only unrecognizable but invisible from the road. It just looks like a wild mass of unkempt shrubbery that you can’t even peek through.

The houses in Colorado Springs and Calhan, where we lived in my teen years, were, honestly, filled with just as many bad memories as good, so I don’t really want to visit them again anyway.

But the one house I could always count on was Grammy and Grandpa’s house: that big, beautiful house covered in cedar siding that stood proudly on the hill overlooking Woodland Park, with a majestic view of Pikes Peak.

I could always call that house home. Or at least stop by and see a friendly face.

Until now.

By the way… in case it isn’t obvious, I’m not upset at my grandparents or anyone else in my family. I’m just having a hard time dealing with the fact that 35 years of expectations, hopes, dreams, and memories came crashing down so quickly, and I’m not sure how to handle it all.

The house doesn’t belong to me. It’s their house: they can do whatever they want with it. Again, I’m happy for them. But still, I feel loss. So much loss…

It’s not the loss of a simple house made of concrete and wood that makes me sad. The house is just a symbol that represents love, relationships, celebrations, milestones, holidays, and, ultimately, family. And I’m sad that that’s gone now.

Maybe when I make my millions, I’ll buy it back from the new owners and turn it into a boarding home myself. I can just see it now: “Pa Stauffer’s Boarding House.” And I’ll put the cross-stitch back on the walls.