The BBC Asked Me What I Thought About the Book “Women Talking.”

As it turned out, Miriam Toews didn't like my questions, and I didn't like her answers.

For the past few years, I have been on a journey of rediscovering my family’s Mennonite heritage.

In 2020, my youngest brother died at age 18 from a heart attack. His sudden, unexpected death put me into a tailspin, and I began going through a personal crisis that caused me to re-analyze just about everything about myself: my beliefs, ethnicity, faith, family, and more.

In the years since his death, I have been knee-deep in research on the Stauffer Family: who we are, where we came from, and why we do things the way we do. One of the most notable elements of our family history is our identity as Mennonites.

Over many nights and weekends, I’ve poured hundreds of hours into genealogical and denominational research, uncovering the history of the Stauffers, our ethnographic roots, and, where possible, trying to understand who Mennonites are and, most of all, what all of that means.

Aside from the bare basics, like taking a DNA test and filling out my family tree, I decided to take this to the next level. I’ve spent thousands of dollars hiring a professional genealogist to verify the dates and locations of births and deaths of Stauffers.

I also hired one German language expert to help me translate family letters written in indecipherable handwriting and another translator to help me demystify the carvings on the headstones of the many Stauffers buried in Mennonite cemeteries across Pennsylvania.

I’ve listened to multiple recordings of people speaking in my family’s historical tongue, Pennsylvania Dutch, the language of Swiss Mennonites, and I’ve found digital copies of The Ausbund and The Zion’s Harp, old Anabaptist hymnals my family would have used while singing in their “Meeting Houses” (what Mennonites called their church buildings).

I’ve done interviews with subject matter experts on Mennonite history, practice, theology, and tradition. Sometimes, I interview academics, including a PhD from the Center for Anabaptist Studies at Fresno Pacific University and a PhD at the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies at Elizabethtown College.

Other times, I’ve met with Mennonites in person and interviewed them via email, phone, and Zoom to ask them about their own lives and experiences. This has included talking to current Mennonites, former Mennonites, conservatives, and liberals.

I’ve watched multiple documentaries, listened to several podcast episodes, and read many memoirs by people who are Mennonites, people who are similar to Mennonites, like the Amish, and people who aren’t similar to Mennonites at all, but come from similarly conservative, insular communities, like Hasidic Jews.

This isn’t hard to do: deconstruction stories abound online these days, and I’ve spent years carefully considering many people’s stories, whether I agree with their final conclusions or not.

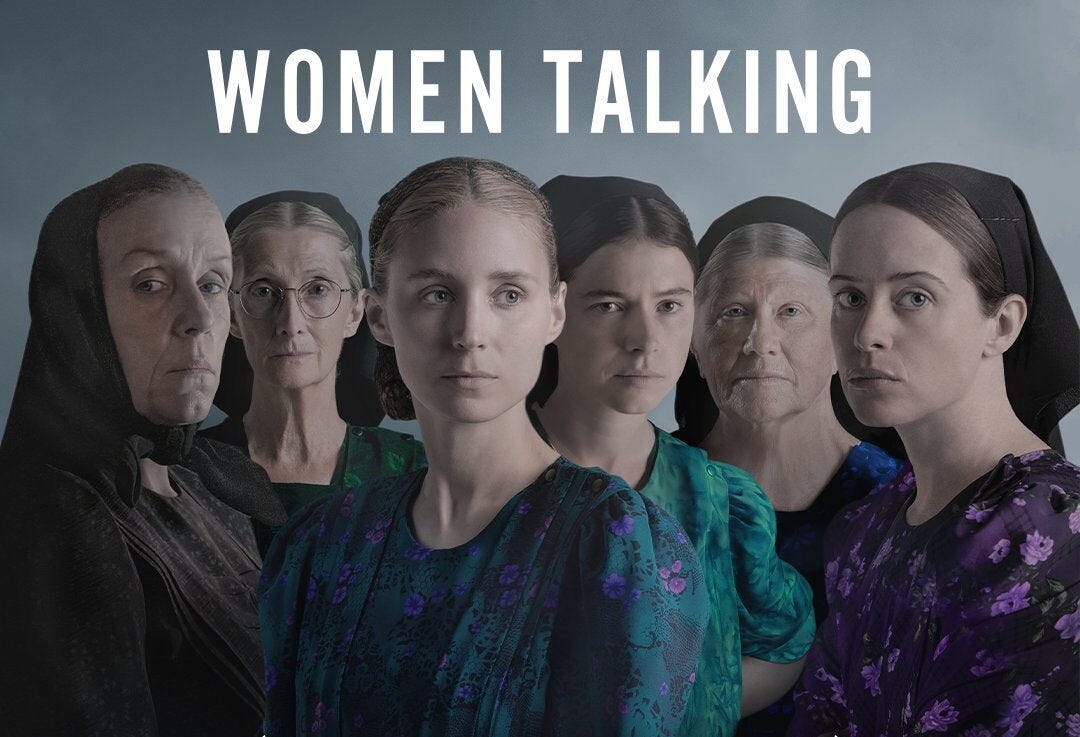

As I’ve done this, one book I discovered was “Women Talking,” by Miriam Toews—a Canadian woman with an impossible-to-spell-and-pronounce last name.

When I first found it, I wasn’t interested at all, mostly because it said “a novel” on the cover. I was not interested in fictional stories: I only wanted to read real stories about real Mennonite people, families, and communities.

I also wasn’t interested because it seemed like yet another angry tome from a woman who ran away from a conservative community and now feels the need to shit on everything and everyone she had just left behind.

For whatever reason, this is our society’s favorite kind of story right now, and while I’ve read and listened to a good deal of them, I have serious problems with most of them.

But then I saw that “Women Talking” had been turned into a movie, and that made me reconsider, especially when I found out it was based on a true story.

But, confusingly, it was based on a real community that didn’t involve the author at all… I thought. Or did it? I couldn’t tell.

The story itself was absolutely stranger than fiction: in a remote Mennonite community in Bolivia (yes, Bolivia, the country in South America), a scandal had been uncovered where some men had found a way to drug women and rape them, over and over, for many years.

Reading the allegations online, everything seemed far too crazy to believe that any of it could be true at all.

Really, young men climbing through windows late at night, spraying sleeping women with an anesthetic gas meant for farm animals, raping them, then escaping without ever being caught?

Then these women wake up in the morning with mysterious bruises on their bodies, and the community is abuzz with rumors of “ghost rapes” happening to them in their sleep?

This couldn’t possibly be real.

Only Stephen King could come up with such a perverted horror story where an invisible Incubus rapes innocent women at night, then vanishes in the morning.

To top it all off, all of this was set in a place filled with the quietest, most peaceable people on earth: Mennonites?

This couldn’t be true. Nothing about it was believable.

Placing a psychotic sexual thriller in a Mennonite colony in South America was just too on the nose. It seemed like a bad comedy, like the antics taking place in the many levels of hell in Dante’s Inferno.

But no. I discovered that this awful B-movie film script wasn’t just a novel, despite the book displaying “a novel” on the front.

Incredibly, it was all true.

Well, wait, it was mostly true.

Or, hold on… just bits and pieces of it were true.

Actually, I couldn’t tell—which parts were real and which parts were fictional? This was all very unclear and getting more confusing as I kept learning more.

Where did the truth end and the fiction start? And more importantly, I wondered: if this is a true story, why would someone write a fictional account about it when they could just write about what actually happened?

I had to know more, so I decided to read the book. Well, to be clear, I got the audiobook on my phone and started listening to it. As I did, I posted a screenshot of the audiobook on Twitter (now known as “X”), saying that after avoiding it, I was “timidly giving it a chance.”

I didn’t really expect anybody to respond, so what happened next shocked me.

I was instantly followed by the BBC’s World Book Club, which sent me a message saying they would “like to hear my thoughts” on the book.

Wow, that was weird. The BBC, as in the British Broadcasting Company in the United Kingdom? That enormous institution that used to put out made-for-TV movies like “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe” when I was a child? That BBC?

…and they wanted to ask me what I thought about this random book about Mennonites in Bolivia that was written six years ago?

No way. That didn’t make any sense; surely, it was a prank. I almost clicked the “spam” button to delete their message. I was sure it was a scammer trying to make fun of me or take advantage of me somehow, and at any moment, this user would request that I send money.

But fast forward a few weeks, and after a few email messages back and forth, it was clear that, yes, this actually was the BBC, and they actually wanted my opinion on this book that had come out two years before the COVID pandemic hit and my brother had died.

How very, very strange.

It turns out they were going to be hosting a book club and a live reading with the author of “Women Talking” in Toronto, Canada, in June of this year and were asking fans to record themselves reading their questions and submit them via email to be played live during the interview.

So I finished listening to the audiobook, carefully writing down notes about it, and thinking about what I wanted to ask her. As I read (listened to) the book, I did indeed have many questions. The first and most obvious of which was:

“Why was this book about women in a Conservative Mennonite community in Bolivia written by someone who is NOT a woman in a Conservative Mennonite community in Bolivia?”

This, I thought (and still think), is exceptionally confusing and borders on being deceptive.

I think most people who hear about this story, read this book, or even watch the movie it has turned into will think that it was written by a woman who actually lived there and actually experienced these things.

But she didn’t. In fact, Toews, from what I can tell, lives in Canada, and has always lived in Canada.

She seems to come from a relatively “normal” community of Russian Mennonites—the same Mennonites that built and founded the Mennonite Brethren church I attended in California from the day I was born until the day we moved to Colorado in my teens.

(On a side note, we knew people at our church with the same last names as fictional characters in the book, like Thiessen, Epp, and Friesen).

So… what gives? As a journalism major, this kind of scenario gives me pause and makes me nervous. It’s not exactly a conflict of interest and isn’t precisely unethical, but it seems like she’s claiming a level of familiarity with the subject matter—the lived experience of rape victims in Bolivia—that she does not actually have.

It certainly feels misleading.

My second question also seemed extremely obvious, and I felt it hovered like a dirty cloud of brown smog over the women doing the actual talking in the book the entire time:

“Why is this author writing a fake story with fictional dialogue spoken by pretend characters when there were real women who actually experienced these things in real life?

Why didn’t she just interview them and tell their stories? Why invent a sensationalized scenario about a real scandal? What is the point of that?”

I understand that if the people you’re writing about are long dead, you have to get creative, trying to reimagine the lives, conversations, and circumstances that are gone forever since you can’t ask them anymore.

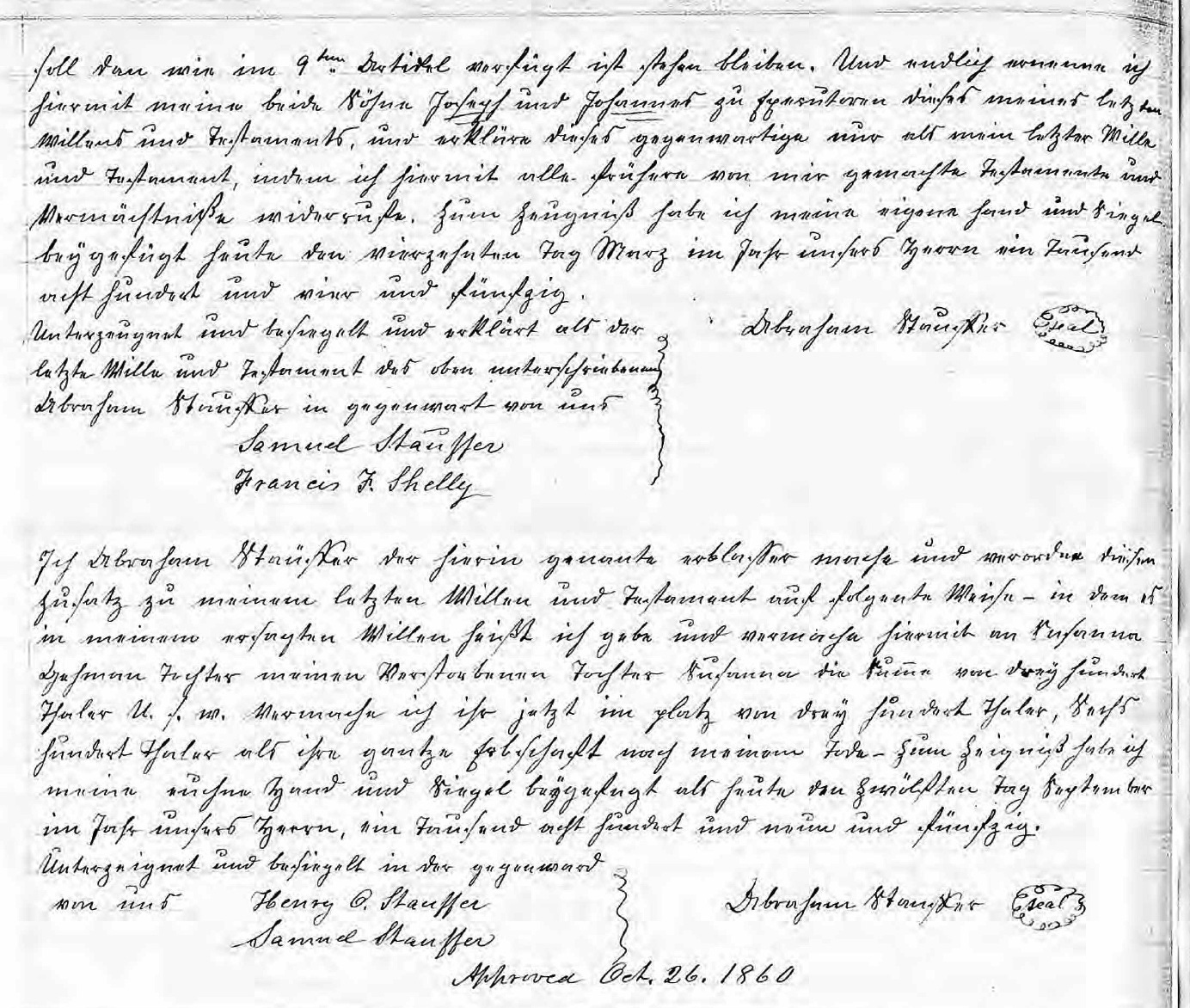

Take my family, for example: when I was doing my research, I found a digitized scan of the “Last Will and Testament of Abraham Stauffer,” handwritten and notarized in 1860.

It was written in Kurrentschrift, an outdated form of German cursive handwriting that is so old and outdated that nobody uses it today. I had to find a special translator who knew archaic German writing to help me figure out what it said.

That document, when it was translated, provided a beautiful insight into a man who loved his wife and family dearly and took careful pains to provide for them after his death (which was just four months later, as it turned out).

This brought up so many questions for me. What was his life like in Pennsylvania the year Abraham Lincoln was elected? Did he like that he had the same name as the new President? What did he grow on his farm? What did he look like? What was his favorite song? What were his hopes, dreams, and fears? How did he meet his wife?

I couldn’t ask him any of these things, of course, because my fifth great-grandfather died 164 years ago. Anybody and everybody who ever knew him also died over a century ago.

There is no living person on the planet who could possibly remember him or what life was like for Mennonites in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, in the 1820s when he first became a father.

The best we can do is imagine what his life was like by finding written records, such as his will. Only after finally translating that obscure script into English could we unlock the only first-person writings from any Stauffers before the mid-1900s. And it really didn’t say much aside from financial instructions to follow after he passed away.

What does all of this have to do with “Women Talking?” Everything.

So far as I can tell, the “Women” in “Women Talking” are not only not fictional; they’re also not dead. We don’t have to imagine what they thought or went through. They could tell us, perhaps, if we dared to ask.

Or, maybe, just maybe, they don’t want to tell us.

That fact alone makes the premise of a book like “Women Talking” astonishing in its audacity: it’s a fictionalized retelling of real people, very likely in an inaccurate, non-historical way, to serve a specific agenda, told without consent on behalf of women who may very well disagree with it or don’t want it to be told in the first place.

But we’ll never know because nobody asked them.

What is the point of that? Why would you do that?

After finishing the audiobook, I wrote out six questions and emailed them to the BBC for their feedback. Here they are.

Question #1: The behavior of some of the women was very jarring and baffling to me and seemed totally unrecognizable for Mennonites. For example: Salome, Neitje, and Mariche use the f-bomb (“f*ck”), Salome calls someone “shit for brains,” etc., and Mejal and Salome smoke cigarettes.

Do you know of anybody in Conservative Mennonite communities like this? If not, where did you come up with this idea for introducing more worldly characters and how do you feel it helped move the story along?

Question #2: For several years, I purposely avoided reading your book. As a man raised in a Mennonite family who comes from a long line of Mennonites, I was afraid it would paint all Mennonites with a broad brush stroke in an unflattering light. When I first heard about what happened in Bolivia, I obviously was shocked and horrified.

At the same time, though, I've spent my whole life with people treating my family like crazy people, extremists, fundamentalists, and outsiders. Even using the term Mennonite in some circles is enough to either entirely confuse people because they're not familiar with us at all or to make them wince with recognition.

Did it concern you that writing a fictionalized story based on a true account would cause even more ill will toward Mennonites in general, especially for those who have no connection at all to the communities in South America where these crimes happened?

Question #3: The book says it's "based on a real-life event," and I get that. But how much of it was real versus imagined? Was 100% of the conversation in the room your invention, or did you weave in bits and pieces of the real story or real quotes?

Question #4: From what I gather, you're from Canada and never lived in Bolivia, correct? If so, how did you conceive of a story in a community you weren't a part of? Did you interview the women? Did you visit Bolivia at any point?

Question #5: Have any of the women who lived through the ordeal read the book? If so, what did they think about it?

Question #6: What was your goal with this story? What do you want the readers to take away or conclude? Are you asking anything of them in terms of taking action, having self-reflection, etc.?

I thought long and hard about these questions over several days. Looking back on them now, I’m proud of them. I stand by them. I still want to know the answers to them.

After a few days, though, I got a surprising response from my contact at the BBC, who said they have “very strict rules on language” and that I couldn’t use words like “the f-bomb and shit for brains.”

This literally made me laugh out loud, and I thought it was quite ironic.

I didn’t write those words. Miriam Toews did.

So the BBC had no qualms with featuring an author who wrote phrases like:

“How can those two scrawny shit for brains prevent all of us women from leaving[?]”

“Motherf*cker, are you interested in having your brains smashed in?”

“She calmly tells Salome to f*ck herself.”

…yet I’m not allowed to refer to those quotes when asking her a question about them?

That is totally nuts. The UK’s lack of free speech drives me crazy sometimes.

The woman in the email told me that they weren’t interested in my third, fourth, fifth, or sixth questions since other people asked variations of those, and they’d already be answered.

So, somewhat unwillingly, I censored myself. I decided to submit a G-rated recording of my first two questions, and I waited… and waited until last week when the recorded episode finally came out.

I was nervous as I clicked “play.” My mind raced as I started listening.

Will they even use one of my questions in the discussion?

Did I go through all this effort for nothing?

Will they try to edit my question to make me sound stupid?

Will Toews misunderstand me in a way that makes me sound like an idiot?

These are things I battle with constantly: almost every time I make myself vulnerable and participate in something like this, I’m often punished, and I regret participating at all.

Maybe it’s because I’m autistic. Despite my best efforts to try to convey the hope, love, and care I actually feel in my heart, sometimes people don’t get what I’m trying to say. (Although I don’t think this is the case, I think they sometimes misinterpret me on purpose to hurt me and make fun of me.)

I don’t know how to stop this, though, and it’s made me want to give up many, many times. But I haven’t so far, mostly because I’m too stubborn and because I am actually curious and want real answers.

This misunderstanding is especially common when I ask questions in an environment where I’m not in the room at the time and can’t respond or clarify (such as via email, text message, or by asking someone else to ask a question for me).

Many times over the years, this has happened: I’ll email in a question to a radio show or some other event, and the person reading off my question doesn’t understand what I’m getting at or misinterprets my motives.

For example, when I was attending a Baptist church as a young man, I emailed a question to Dr. Albert Mohler (President of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary) in 2009 during his radio program. It was a special “Ask Anything Wednesday” show, and I asked about the morality of nudity in art from a Christian perspective.

I wanted to know: what is a solid biblical perspective on creating artistic works with graphic nudity in them. Is it a sin? If so, why is so much historical Christian art filled with nudity?

I patiently waited until he read out my question on his show. And how did he respond? I still have the recording. It was embarrassing.

First, he laughed out loud. Then, he paused, unsure of what to say.

Finally, he said: “Okay, that one's new. I don't think that question's been asked before.”

Well, congratulations to me! I’m constantly being told I ask questions nobody else asks. I don’t know why people are always telling me that, and it’s embarrassing when they call attention to it.

The good news, though, is that Mohler actually followed his opening with, “It’s a good question… it’s a fine line, and you ask a fine question,” then gave a decent answer that took me seriously. I appreciated that. So, I got a serious answer to my serious question, even though it was an embarrassing process.

But my experience asking questions of Toews just made me angry.

First of all, they ignored my first question. That was annoying because it was the more important of the two I sent.

I don’t really believe that there are Conservative Mennonite women out there who smoke cigarettes and shout at each other with such profanity. If there are, I haven’t met any, and if she has, I wanted to know about that.

I’m not saying it’s impossible; I’m saying it’s implausible, and since this was a fictional novel, I wanted to know why she made that choice when the characters were purely her creation. She could have made them like anything she wanted.

Maybe she knows Mennonite women like this, but I don’t. That’s why I asked.

But they either chose not to ask that question at all or, if they did, they cut out her answer. That was annoying.

Second, for the question they did use, her response was rude, inadequate, and entirely dismissive.

Around the 26:00 mark, my recorded voice asked her if she was concerned that a fictionalized story based on a true account would cause even more ill will toward Mennonites in general.

In an irritated tone, she scoffs and says: “Uh, no. Absolutely not.”

What? That’s a dumb answer. It’s shocking, really.

She doesn’t care that her extremely negative book, which portrays a community of Mennonites—that both she and I were not a part of—in an overwhelmingly negative light, could make other Mennonites look bad?

Why not? What kind of a person doesn’t care about that?

She then ignored my main point and, angry at me, I think, tried to swat me away by saying:

“I believe that… readers would… understand that not all Mennonite men are rapists. So, no, I'm… not worried about that.”

Here, she’s being either intentionally obtuse or extremely lazy.

That is not at all what I asked. Not even close.

By this point, I don’t really care what she’s written anymore, and I’m starting to regret spending any time listening to her book and answering these emails from the BBC. Also, she’s proven that my initial suspicion about the book was absolutely correct.

What I was very clearly asking was: “How do you write a story about a community where evil things happen without besmirching or impugning every member of that community?”

Maybe Canadians are different, but in America, people—normal people—are very concerned about this. We're extremely careful to add disclaimers, caveats, and asterisks when we talk about a particular people group where crimes are concerned.

We say, either explicitly or implicitly, that “Not all people who look like this, act like this, or come from this community are guilty of this, but here’s a small case when a few people from this community did commit the following crimes…”

Seriously, it’s almost embarrassing how often publications trip over themselves in an over-abundance of caution to make sure their telling of one small group of people within a community doesn’t implicate the community as a whole.

The level of pandering to Muslims after 9-11 was a classic example. Many Americans went overboard to lavish praise upon Muslims and make sure nobody ever equated imported Islamic terrorism with peaceful Muslims living in America.

But Toews doesn’t care about this at all and didn’t put forth an ounce of effort in this regard.

She waves off this concern entirely, essentially saying, “Nope, don’t care. Can’t be bothered.”

This is a shockingly cold and callous response, and I’m saying this as an autistic man.

Also, carefully note that I did NOT say anything about “Mennonite men.” I don’t know where she got that. She made that inference herself.

I specifically said, “Mennonites in general”—that includes women and children. Why is she reading a male-centric view into my question? Was it just because it was asked by a man?

If that’s the case, this author has very poor listening skills, and it is, ironically, sexist of her to assume that’s what I meant when I never said anything like that.

I can’t imagine being so unconcerned about slandering a whole community the way she has.

Even right now, as I write these words, I’m trying hard not to attack Toews personally—I want to disagree with her in principle while still being fair and not assuming the worst.

Because, unlike her, it seems, I actually care about that.

Also, immediately after dismissing my concern, she then changed the subject entirely and accused me of something very harsh that I did not deserve.

“I feel this is another, you know, battle. I feel that I'm kind of… in almost… at every single event that, that I… that I do, there, there are always one or two older Mennonite men who… who are there to, um, to talk to me afterwards and to discipline me, to tell me that they're disappointed and… and ask me, “Why do I feel it's necessary to air this dirty laundry?” and… and that I'm giving Mennonites bad name and, and so, and I… and I'm used to it.”

WHOA: stop the presses… this is getting outrageous.

First of all, I am not “an older Mennonite man.” What is she even talking about? From what I found on her Wikipedia page, she is 60 years old. I’m 38. She is 22 years older than me.

Second of all, I’m not there to “discipline” her. Not even close.

Let’s reframe this in the proper context, shall we?

Who asked who to this dance?

I can totally imagine a couple of older men with white beards from Conservative Mennonite communities driving to her events to crash her party, harass her, and tell her how disappointed they are in her and that she should stop.

But that is not at all what’s happening here. Here’s what is actually happening:

I bought her audiobook (which she profits from, so she’s welcome for that).

I listened to her story.

I was ASKED by the British Broadcasting Corporation—the group running this book club event—to send in my questions to them and participate in a virtual discussion.

I sent them my questions.

They approved my questions (well, one of them, at least).

They chose to share it with her during the event that they hosted, and they moderated.

In short, I was invited to participate, and my opinion was welcomed. That is something entirely different than what she’s implying.

I think she’s shocked that I would ask such a bold question.

But I’m shocked that she’s shocked.

I’m not going to apologize for being tough or asking critical questions. She’s an adult. She wrote a critical book about a tough subject matter. She can handle it.

Also, she’s trying to invalidate my question by lumping me in with other men who have nothing to do with me, and she’s doing it in bad faith, trying to shut me up, probably just because I am a man.

This is where I struggle to take people who write books like this seriously. I listened to this audiobook because I am interested in hearing women talking. But if the author is such a misandrist that she can’t even stand to hear a man speak, that means the goodwill is only flowing in one direction.

To put it another way, I listened to “Women Talking” for six hours. I have questions. But she can’t be bothered to listen to a man talking... for 60 seconds?

Not even “men” — just one man?

If I had more time, and if I were actually in the room during this book club meeting, I would have liked to push back on her rude and dismissive response… or at least try to redirect her to answer what I actually asked.

I wasn’t even specifically talking about myself: I was clearly talking about the thousands of kind, faithful Mennonites all over the world, who are some of the friendliest, most hospitable, honest, hardworking Christians I have ever met in my life.

I was talking about Mennonites across the globe who are in the “Mennonite Your Way” directory, where they’ve literally opened up their homes to strangers. I was talking about the Mennonites who volunteer for the Mennonite Central Committee, helping victims of war, famine, natural disasters, and starvation, all at no cost, no questions asked.

As a reminder, I even said: “…especially for those who have no connection at all to the communities in South America where these crimes happened.”

I think her book is throwing gas on the fire of the poor perception of Mennonites by inventing a fictional dialogue to create (or perpetrate) the perception that Mennonites are mean people who live in harsh, loveless communities where women are subjugated, powerless, and regularly sexually assaulted.

Of course, there’s more to the story than that. NOT ALL MENNONITES ARE LIKE THAT. In fact, very few are. Obviously.

But when you write a book about a true story and fill it with fictional dialogue that is clearly designed to make the men look as bad as possible, the women as powerless as possible, and the situation as hopeless as possible, you’re created what people will perceive as the indisputable truth, even when it isn’t.

They’ll find the book at the bookstore, pick it up, see a picture of the author, and read the jacket bio that says, “Miriam Toews is a Mennonite writer…” and they’ll think:

“Well, she’s the expert. She knows what she’s talking about. Mennonites sure are f*cked up. I’m glad she escaped from that hellhole.”

Except that she didn’t live there. And she didn’t escape. And Mennonites are not f*cked up.

I suppose my mistake in all of this was that I asked a question in good faith to a writer who has made a living creating books that portray Mennonites in a bad light.

If your financial success depends on your ability to constantly tell and retell the world just how horrible life is growing up as a Mennonite, I guess you have to keep churning out book after book reinforcing that theme.

Seriously though, nobody knows about Mennonites! I tried to explain that in my question.

Do you know how many times I’ve met other Christians, and when the topic of denominations comes up, and I say, “I was raised in a Mennonite family,” their jaws just drop in astonishment?

“A what? Mennonite? So, you’re basically Amish? Did you live on a farm? Did you do barn raisings and stuff like that?”

It’s become so awkward that in my adult life, I just stopped talking about it.

People think it’s weird because they don’t know any Mennonites. Or they only think they know about them because they’ve heard the term in a movie or on a TV Show.

When I was younger, people would have remembered the movie “Witness,” where Rachel, the Amish woman, talks about her neighbors who—shockingly—have electricity! “The Gunthers across the valley… they're Mennonite,” she says. “They have cars and refrigerators and telephones!”

When kids at the Baptist church I attended in my teens found out I came from a Mennonite family, they literally said things like:

“Whoa, you’re Mennonite? Weird, so you’re like Amish people, but you have electricity and phones and stuff?”

My goodness, even my wife was confused when she first met me.

“Your family is Mennonite? What does that even mean?”

Growing up as a Baptist, first in California and then in Colorado, she had met precisely one Amish family and precisely zero Mennonites.

More recently, today, a lot of people only know about Mennonites from videos online. Only when the NBC sitcom “The Office” came out in 2005 did we finally get our very first folk hero.

Dwight Schrute, the irascible full-time paper salesman and part-time beet farmer, has provided more insight into Mennonites and Pennsylvania Dutch culture than just about anybody else in modern America. And, as I mentioned in my question to Toews—who doesn’t care—he indeed seems to come from a family of “crazy people, extremists, fundamentalists, and outsiders.”

But even then, the Mennonite connection is still not clear. We don’t know whether he is actually from Amish or Mennonite stock: he uses both terms to describe his family, sometimes interchangeably.

Aside from clips from The Office, most of the other videos about Mennonites you can find online are not at all flattering and usually pick on the insular Mennonite communities in Central and South America.

Search online for videos about Mennonites. Most have titles like “Who are the Mennonites?” “What do Mennonites Believe?” and “How are Mennonites different from the Amish?” — because people don’t know anything about them.

…and now, of course, there’s this new movie, “Women Talking,” based on this very book written by the author I’m having a discussion with through recorded messages at a book club in Canada.

And it very clearly paints Mennonites in a bad light, as though they’re all people who live in dangerous communities filled with criminals.

She even admits this in the book club discussion: at one point, she says:

“I think it’s… easy for us to think of this group of people, Mennonites, you know, as kind of… freaks in a sense, religious, almost cultish.”

Umm, that was my entire point.

And the fact that she’s making it worse doesn’t concern her at all? That is very frustrating. How bizarre.

Earlier this year, I went to an island off the coast of Venezuela and spent a whole day at a Mennonite Mission run by Conservative Mennonites that look awfully similar to the ones portrayed in the book (and the movie) “Women Talking.”

They were wonderful people. I went to church in the morning, then Sunday school afterward (which was segregated by sex, of course), and spent the afternoon with two of the elders and their wives.

We had a great time eating mangoes and fried breadfruit, talking about the Bible, what it’s like being Mennonite, speaking Pennsylvania Dutch, living in a tropical environment, and a lot more.

It was hard for me not to think: “I wonder if they know that there’s a popular movie out right now that is telling a horrible story about Conservative Mennonites in South and Central America.”

I didn’t want to bring it up. What would they say? What would they think? For all I know, these ladies might even know some of the women in the colony in Bolivia.

It was also hard for me not to think about how, where I currently live in Southern Arizona, if you were driving down the street and saw these same women in their conservative dress and head coverings, MOST people who live here would probably say something like:

“Oh, wow, those women look like they’re Amish, or maybe… Mennonites. You know? Mennonites? Like that one movie about those rapists in South America?”

That’s a hard thought for me. I know the rapes happened. I am sympathetic toward that.

But what I can’t understand is why a writer would take a true story that very few people have heard of, invent a fiction about it, and amplify that story so that what most people hear is the fictional part and not the truthful part.

Also, to her point about Mennonite men—a point I did not bring up, remember—does Toews not know or care that the Manitoba colony in Bolivia has (or had) between 1,000 and 1,500 men in it and that the total number of men who were convicted of being rapists was precisely eight?

That’s eight —as in, “fewer than ten.” In a community of over 1,000 men, that is literally less than one percent.

Does Toews not know that all anybody knows (or thinks they know, rather) about the Manitoba colony now is that it’s filled with a bunch of sex-crazed rapists who drug their victims? Yet, it was just eight men who committed these crimes.

In all of the six hours it took me to listen to “Women Talking,” the fact that only eight men were involved was barely hinted at: it was acknowledged once in “a note on the novel” on the very first page that the rapes were committed by eight men.

Hoever, for the rest of the entire story, it was always implied that “the men” who were away in town, seeking bail money were all of the men in the entire community, as though every single man was complicit in the crimes when, in fact, over 99% of them were not guilty at all.

So, here we are now. I asked what I asked; she said what she said. Now what?

I didn’t like the book. I didn’t hate it, though. Toews is a decent writer. I liked the symbolic imagery of the dragonflies who embark on a journey they won’t see the end of during their own lifetimes. I also liked the narrative technique, where the entire story is told from start to finish in just one room: the hayloft. That’s clever.

It was bizarre for her to leave out all quotation marks, which were not applicable in the audiobook version, but made the print version almost unreadable. Who is talking, and when? Why is this college graduate writing dialogue without punctuation, as though she never even finished the third grade?

But I really didn’t like the way she ignored my questions. I still didn’t get a satisfactory answer to any of them. I wouldn’t care all that much, except that I was asked for my opinion!

Before that, I was minding my own business, listening to her audiobook just like the 500 other audiobooks I’ve listened to since I first picked up the habit.

In case anybody thinks I’m being too harsh, like I just don’t know about victims of sexual assault, or that I don’t care about rapists getting their due, and that I’m being flippant about the horrors these women experienced, I ask you to consider two things.

First, I experienced sexual molestation myself when I was a child. I have had to grapple with this for decades, as this secret shame has nearly driven me to suicide over the years.

So do not tell me I’m unsympathetic to those who experience sexual trauma and want to fight against the power structures that protect perpetrators who are older, stronger, and in positions of authority over you. I know ALL about that.

Second, someone I’m very close to was a rape victim as a child. This person was subjected to years of secret, hidden sexual assault and terror.

I was there when this sexual abuse was initially discovered. And I watched, first-hand, as adults tried to hide the crime, cover it up, and prevent law enforcement from getting involved.

I was the FIRST person to say, “We need to call the police right now,” and was told, “No. We’re not going to do that.”

So do not tell me I don’t understand wanting to see sexual predators behind bars. I do.

However, where books like “Women Talking” and authors like Toews completely lose me is when they present a story about a horrible subject matter—especially when it’s true—without any hope.

We need hope. There has to be hope.

As part of my genealogical journey, and as I work on writing my own memoirs, I have personally spoken to multiple Conservative Mennonite women, some of whom were the victims of abuse.

Two of them, in particular, stand out to me.

The first was a woman who came from a Swiss Mennonite family who spoke Pennsylvania Dutch and grew up in Pennsylvania, just like the Stauffers did historically. The likelihood that we’re related is actually quite high since we have matching surnames in our family trees.

She explained how her father was an extremely angry man, verbally and physically abusive.

That is an awful experience, and I’m very sad for her. Nobody should go through that.

And yet… she told me that she was able to move on. She grabbed onto the happy memories from childhood—anything she could find—that were worth remembering. And she’s now an adult living a functional life.

In other words, she has hope.

The second woman I spoke to came from a Russian Mennonite family that spoke Plautdietsch, just like Toews herself and just like the women in the Manitoba colony in Bolivia. She was the daughter of Mennonite Missionaries in South America.

She explained how she was sexually abused as a child by an older, married man who was a serial rapist and contracted gonorrhea as a result.

That is an unspeakably awful, traumatic, life-altering horror. Of course.

And yet… She is also now an adult living a functional life.

She also has hope.

When I finished listening to “Women Talking,” there was no hope. It was like a soap opera: so dark, so serious, and so dramatic, it makes you wonder: “Why did I read this?”

Or, more specifically, as I noted in my fifth question, which the BBC didn’t ask:

“What was your goal with this story? What do you want the readers to take away or conclude? Are you asking anything of them in terms of taking action, or having self-reflection, etc.?”

I still have no idea, having listened to the audiobook and even now, after having listened to the book club interview.

Toews’ book about the Manitoba colony (confusingly renamed to a fictional “Molotschna colony” in the book) is a story without hope. It is utterly pessimistic, nearly nihilistic. The ending provides no comfort, either, or even a conclusion.

For years, I’ve said that the saddest story I’ve ever read is John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath.” Like “Women Talking,” it is also a fictional tale based on real people who actually existed, and it was also turned into a movie.

At the end of the book, the 19-year-old Rosasharn Joad starts breastfeeding the old man in the train car, as the narrator metaphorically zooms out, and the scene fades to black. And readers are left in shock, wondering… “What on earth did I just read?”

I had a similar reaction to Toews’ book.

I don’t know what to do with it. I still have so many questions about it—and I literally got to ask the author questions about it!

“Women Talking” is a bleak tale that makes you want to give up entirely on humanity. There is no solution, no resolution, and no hope. You’re left hanging with an incomplete thought, wondering: “What did I just read?”

Yet here’s the weird thing: the women in the Mennonite community in Bolivia aren’t fictional.

They are real. They are still alive. Something did happen, and they weren’t left hanging. Somehow, they did make a decision, and they did move on. Why are we pretending nobody knows?

Why does a writer in Canada get to make a fake version of their story and tell it as though that’s all we need to know about it?

Did she interview any of these women? Did she even visit the colony? As far as I can tell, the answer to all of these questions is “no.” I could be wrong, but from what I can tell, I don’t think Toews has ever even been to Bolivia.

Additionally, the fuzzy lack of clarity on what’s true, what’s not, and the space between those, as I mentioned, borders on being unethical. So I was absolutely shocked to find out that Toews has a degree in journalism! That fact alone is astonishing.

I was also a journalism student, and treating a true story like this with such a cavalier attitude throws up all kinds of red flags and moral problems. I can’t imagine the trouble I’d have gotten in with my professors if I played fast and loose with facts to create a hybrid story like this in order to sell books.

In the BBC’s book club interview, it’s clear that it’s not just me who is confused about whose story Toews is telling. “Nicole from Toronto” asks Toews what it was like to be 18 and choose to “leave the colony.” Toews has to correct her and say that she didn’t grow up in a colony at all.

It sounds like Nicole from Toronto thinks Toews actually lived in the colony in Bolivia, or at least a colony that was just like it, and Toews has to correct her to say she didn’t.

I am certain this is a common misunderstanding.

Also, her total lack of connection to real people in Bolivia is made explicitly clear at one point in the discussion. Check out this exchange:

Toews: “My sister also knew somebody that was actually in the colony.”

Interviewer: “Wow. Your sister knew someone who was actually in the colony in Bolivia?”

Toews: “Yep. Yeah.”

Interviewer: “What… what did she tell her?”

Toews: “She didn't tell her anything. There wasn't any communication between the two of them, you know, in terms of that.”

Huh? That’s a very strange admission. She’s saying she did have one actual connection to a real victim but that she didn’t say anything at all? Nothing whatsoever?

Finally, at the end of the book club, the interviewer FINALLY asks the question everybody has been wondering this entire time.

Check out Toews’ long, rambling word salad of an attempt to answer this question.

Interviewer: “Readers around the world wanted to know about the real-life women in the Manitoba colony, and they wanted to know if you'd heard anything about how they're doing now?”

Toews: “I've heard various things about, about the women. Some, some of the women together with their families have left, um, most have, have stayed as far as I know. Again, you know, this Mennonite grapevine, um, and, and there are still women in my hometown who, um, you, you know, like I said, are, are related to, to some of the women there who have stayed there. And, um, I've heard that some of the women, who knows whether this is coerced or… or whether they're being pressured, uh, have said that in, in fact, none of this, um, none of this did happen and these men have, you know, been wrongly imprisoned, charged, tried, et cetera, you know, and of course the pressure is, you know, from, from, from the elders to, to bring the men back, to forgive them, and, uh, and to, to sweep this all under the carpet. And, and, uh, it's, it's very, very difficult to, to really know what's happening and whether the women there or the men, you know, whoever, um, from the community are free to speak about it, you know, there are some things you can go online, you can read, you know, Mennonite, uh, press, um, about it, and, and various… and people have gone to the community in order to, you know, to, to help, to, you know, offer various things. But yeah, it's, it's very, it's very much closed off, and it's really impossible to really know.”

Let me be bold and autistic here for a moment and provide Toews with the answer she gave me (but shouldn’t have), which she should have used here. Here’s how this discussion should have ended:

Interviewer: “Readers around the world wanted to know about the real-life women in the Manitoba colony, and they wanted to know if you'd heard anything about how they're doing now?”

Toews: “Uh, no, absolutely not. I'm not worried about that.”

That would be the correct answer. She has no idea.

Here’s another aspect of this whole thing that really bothers me. How many of the women who were victims of these horrendous sexual crimes have gotten paid for their story, which has been retold, truthfully in part and fictionally in part, first in a book and now in a movie?

Has a trust fund for the survivors been set up, where these women get a portion of the proceeds of the royalties? If not, how is that not trauma exploitation? How is that not profiteering off of violence and the suffering of others?

Toews is the author of a book that is now an “international bestseller,” which was eventually turned into a Hollywood movie that won an Oscar. She is going around on book tours hosted (and funded) by the BBC in places like Toronto, Canada.

Does anybody else see how utterly ironic this is?

Am I the only one willing to cry out that the emperor has no clothes? She could not possibly be more disconnected from the women she wrote about if she tried.

Someone’s getting rich off of this story. But it isn’t the women in the story.

When I was growing up, I remember when the Disney movie “Pocahontas” first came out, and we Stauffer kids asked our parents if we could see it.

They had a fascinating perspective on it. First, they went to go see it together in the movie theater and, upon returning, said, “No. You can’t see it.”

“Why not?” I asked, disappointed.

“Because it has nothing to do with Pocahontas. It is completely historically inaccurate; it’s basically a complete fabrication. The movie might as well not even be called ‘Pocahontas’ at all.”

“So what? What’s wrong with that?” I asked.

“We don’t want you to get the idea that what happens in that movie is what really happened. Pocahontas was a real person but what happens in that movie is fictional.”

“Who cares?” I persisted.

“We don’t want to support that,” they said.

“Millions of people are going to see the movie in theaters and say, ‘Okay, so, now I know the story of Pocahontas,’ but they’ll be wrong. It would be better to not see it at all than for you to think you understand a real person’s story when you don’t.”

I didn’t understand this at the time. I thought it was mean and unfair. Now, I think there’s some real wisdom in that perspective.

The same could be said for “Women Talking.”

But hey, Toews’ book is selling like hotcakes. So, good for her, I guess. Maybe that’s all that matters.