Helping My Teenage Daughter Write a Book and Sell It on Amazon

When in-person learning was canceled during the pandemic, we used the opportunity for her to do something special: write a real book.

When my daughter turned 15, it was 2021, during the height of the insanity of the pandemic where schools were canceling in-person learning and trying to teach remotely, with… completely predictable (and awful) results.

She had a really hard time adjusting to the shift to online learning and was not doing well in school. Add to that the fact that we had recently moved to a new state, and her life was, essentially, no fun at all.

She’d spent the past year logging into a computer and trying not to fall asleep in her chair as a teacher droned on in the background, occasionally asking: “Can everybody hear me? Does anybody have a question? Anybody? Nobody?”

It was just… destined for failure for many reasons.

We now lived over a thousand miles away from her old friends, and she was unable to make new friends at her new school because everything was online, and they hadn’t met face-to-face.

By the time summer rolled around, she was not only unfamiliar with the people around her but also the surroundings: having taken classes from a laptop in the living room, she rarely had any reason during the school year to venture outside in the daytime. So during summer vacation, she needed something to take up time, give her something to do, and inspire her.

She had wanted to be a writer for many years and had constantly been scribbling small stories in notebooks that never saw the light of day, so I gave her a challenge for something that would be hard, but worth doing.

“If you write a complete story from start to finish, I will edit it for you and help you publish it and sell it on Amazon.”

So that summer, we got busy!

I guided her through the entire process: from creating an outline, writing out the basic premise of the story, cutting it up into chapters, deciding on artwork, sketching out profiles of the characters, and more.

She originally decided to use the story she’d been writing bits and pieces of for years: a fantasy novel about dragons so we spent a few weeks going down that road until she realized that this was a much too ambitious story for a summer project. So, we scratched the whole idea and started over.

That was a really hard lesson: it was good to learn about measuring the scope of a project before you begin it, but it was also a painful decision to make because it meant we had to throw out weeks’ worth of work that had already been done.

The new idea: another fantasy novel, but this time, a much shorter story about pirates and mermaids.

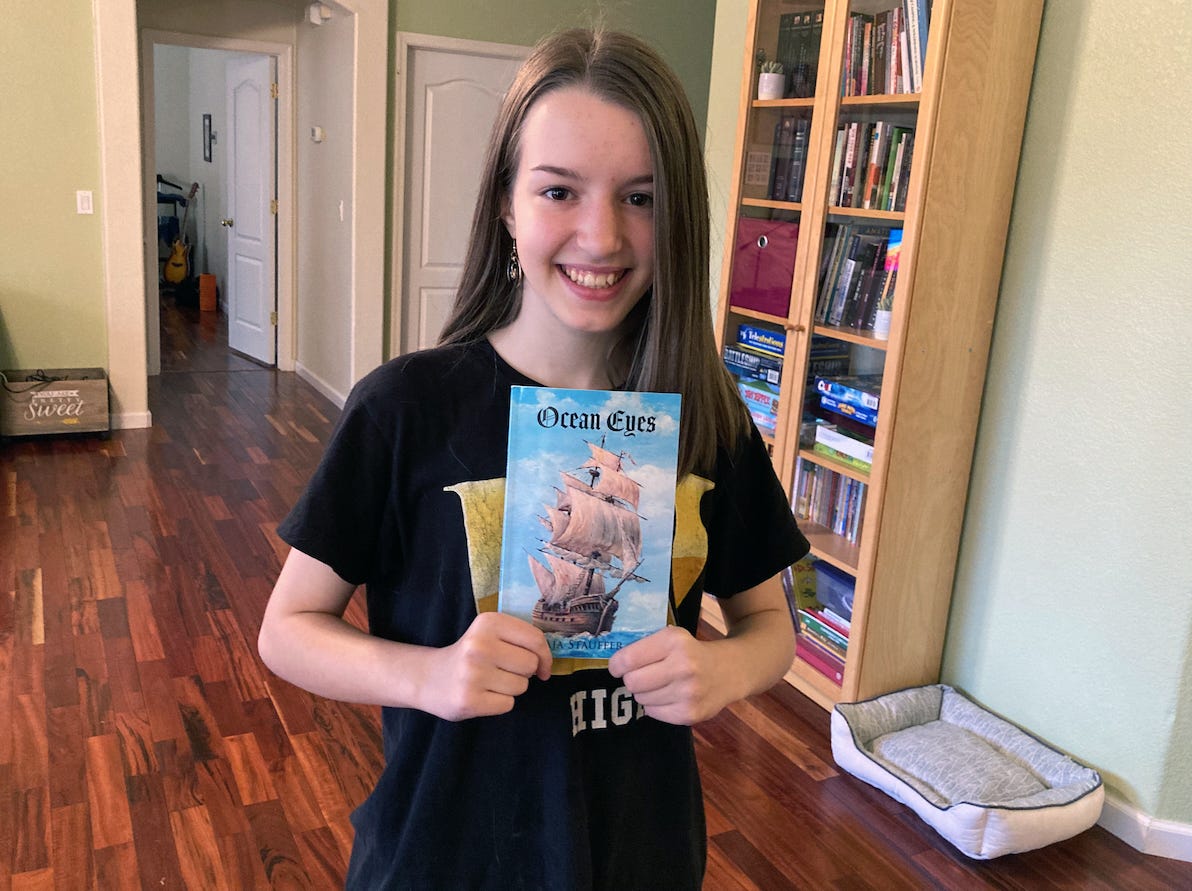

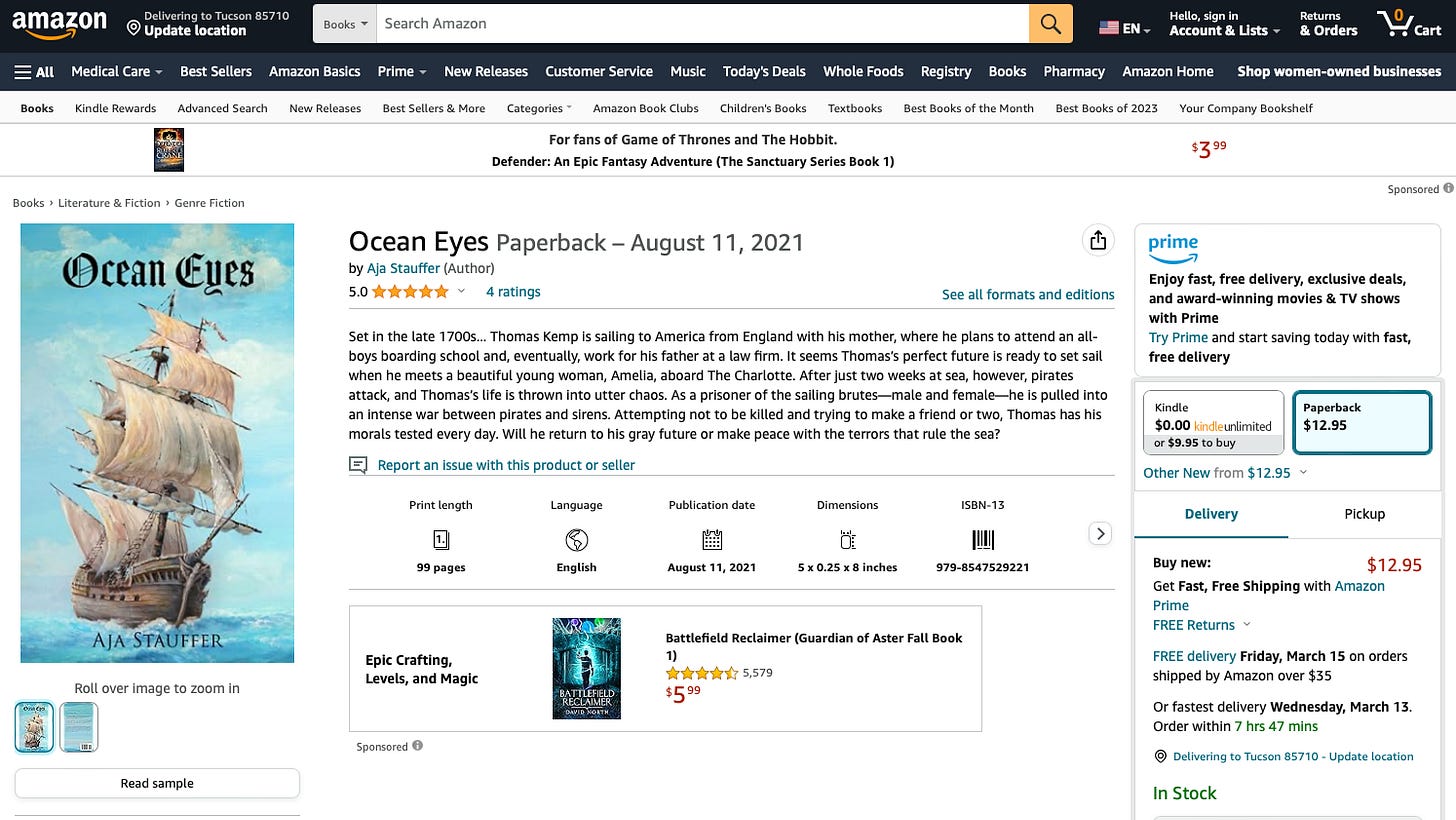

“Ocean Eyes” is what she decided to call it. It would be a story about an English boy who sails to the New World in the 1700s with his mother, but then disaster ensues as their ship is raided by pirates and he’s kidnapped. He meets Amelia, a girl his age with a mysterious air and a dark secret.

I loved it. So she started writing, and writing, and writing. She spent days making notes with pens and paper, then writing drafts in Google Docs on a Chromebook, and I would edit them, highlight plot holes, fix the grammar and punctuation, and provide other feedback.

The whole experience was very good: it was fun for me to see her writing skills bloom in a way that everyone else could see, and it was good to give her a finite task with a deadline and an end goal where we knew when it would be completed.

One of the problems with writing is that it’s completely demotivating to “just start writing” without any goals, timelines, or frameworks to clearly define what it is you’re writing.

For example, if you say you want to write a book, you can’t just sit down at a computer and start typing. If you do that, you’ll waste your life with a rambling mess of words that make no sense, have no specific purpose or audience, and don’t actually do anything or ever see the light of day.

It’s like shouting into the void: nobody will hear you, and it’s a waste of energy.

Instead, if you want to write a book, you need to answer many questions first, such as:

What’s it called?

What’s it about?

Who is it for?

How many chapters will it have?

How many pages will it have?

What do I want people to gain from reading it?

Who is my target readership? What other books do they like reading?

If I saw this book on a shelf at the bookstore, which shelf would I find it on, and what other books would it be next to?

Basically, you’ve got to answer the 5 Ws (Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How) before you even get started. If you don’t answer these questions first, writing will become a depressing and pointless task—it will feel like a chore, not something enjoyable, and you’ll dread doing it.

Or, as we learned with this book project, if you answer these questions defining a book’s purpose, intent, and scope one way, then change your mind halfway through, you’ll waste a lot of time.

Wasting time like that also kills your motivation a little bit. Each time you have to course correct, it reduces your energy.

Let’s say that my daughter and I both had 100% energy for the first book idea. (Of course, we didn’t, really, because it was during the pandemic, as I mentioned, so we were both very stressed and burned out, but let’s say for the sake of argument that we did have 100% motivation.)

We started going down that path. Then, she decided to change direction from the dragon story to the pirate story. That killed probably 25% of our motivation, so now we’re at 75%.

As time dragged on, it started sapping our energy naturally as well, so once we got a few weeks in on the second book, maybe we were down to 65% or so. At one point, I think the idea of changing stories once again was suggested by one of us.

Maybe a pirate story was also too big? Maybe we needed to try a third story?

But no! That would have killed even more motivation: changing books a second time would have dropped us down by at least 25% more, so now we’d be at 40%. That’s running at less than half capacity, which would make it feel like it wasn’t even worth doing.

So we had to keep going. We had to stay motivated. She had to keep writing, and I had to keep editing and keep telling her she could do it.

Our solution to the “scope creep” was to decide that when the story became too big or too long, we would add it (at least mentally) to the sequel.

Being able to say “We’ll address that in the sequel” was a really good way to keep moving forward without having to add more writing all the time, increasing the page count, and making the project take longer.

For example, with her first book outline of the pirate book, she said she expected there to be 50 chapters. When it was all said and done, though, it ended up having just 27.

Writing a book as a 15-year-old was, I think, a really good exercise for her in many ways.

For one thing, she had always said she wanted to be a writer. This was her chance to get started: the way you become a professional writer is by writing… so this was the perfect opportunity for her to use the time she had as a teenager to her advantage.

Instead of languishing at home in her bedroom, in boredom and misery, in our noisy house with four other kids that summer… she came to my office with me.

She could sit in front of a computer for hours each day, write hundreds or thousands of words in a peaceful, quiet place with all the time in the world, completely uninhibited and undistracted.

When we drove home in the evening, she’d talk about what she got done, how many more pages she completed, and what new challenges she encountered.

The hardest part of the book, from my perspective, was keeping track of the storyline and characters. Creating a fantasy story about fictional characters that don’t exist in real life is a complicated business: you also have to create a back story for each person and answer many other questions, like:

What is the character’s name, and how do you pronounce it?

Where did he come from, and what kind of accent does he have?

What does he look like, and what does he wear?

What does he care about, and what does he want?

Why is he here in this story, right now? How did he even come into the picture in the first place, and where is he going next?

The single biggest challenge for all the characters is making sure that every character and situation moves the story forward. Do you bring a new person or scene into the story for no reason at all? Do you introduce a character who vanishes and never helps advance the plot?

These are hard to discover yourself when you’re writing a book, and it’s also hard to find when you’re editing a book that someone else is writing: after you read the manuscript once or twice, you start to lose track of everything, and your eyes glaze over.

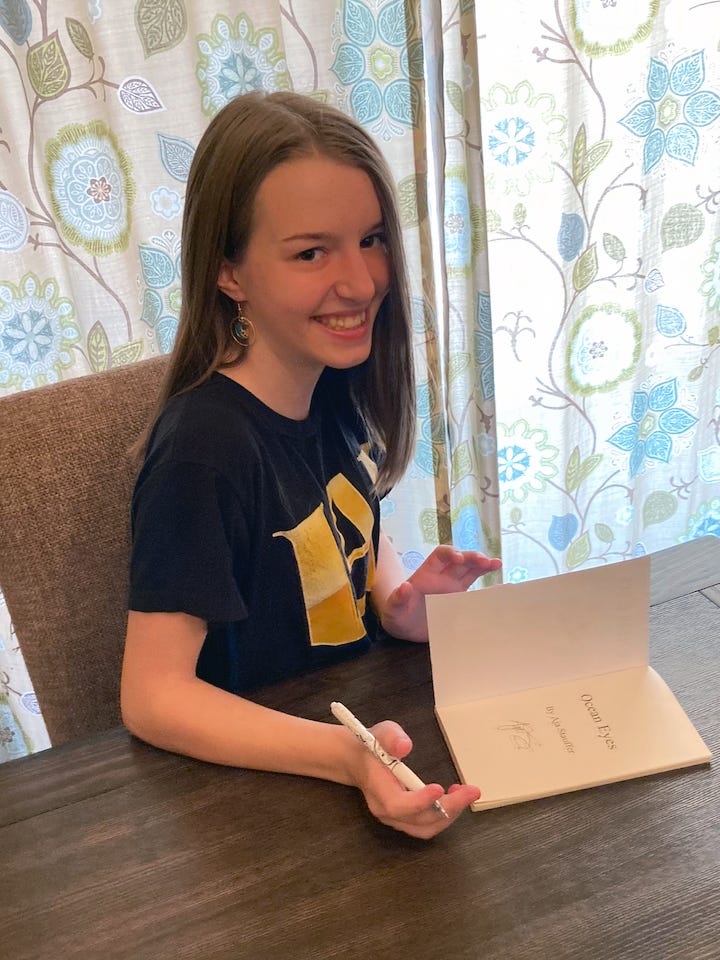

But in the end, we did it. She finished writing, I finished editing, and we tied up all the loose ends and filled in any remaining blanks in the story (or at least I hoped we had).

I took a photo of her to use as her author portrait, she came up with an author bio, I bought the rights to an image we could use for the cover, then designed the cover myself in Photoshop, and we submitted it to Amazon via their “KDP” program (Kindle Direct Publishing).

When it was accepted and went live on the website, it was a total trip for both of us to see her name and picture right there in front of the whole world.

One of the nicest benefits of her now being an author on Amazon with a real-life book (both in print and an eBook) is that other people find this to be very impressive.

Sometimes this has a boon to her professional life. When she recently went in for a job interview, when the hiring manager found out my daughter had written a book that she could look up on Amazon right there on her phone, she found this to be very impressive. I’m sure it only helped her chances of getting the job.

Also, her friends and family members showered her with praise, sending congratulatory text messages, squealing into the phone with excitement, and even buying copies of it to give to other people.

As of today, she hasn’t made very much money on it: I think she’s sold maybe 25 or 30 copies in all. But if she ever wants to pick up where she started and finish the sequel (“Princess Pirate Queen”), she can.

The most ironic outcome of this whole project is that, as of today, she says she’s decided not to become a writer after all. The first time I heard this, I was almost shocked and felt terrible.

Why had we wasted all that time? Was it all completely pointless?

But after a while, I reframed my thinking. Even if her conclusion at the end of writing a book was: “I don’t like writing books,” that’s actually a good outcome. For at least three reasons:

#1: It was worth doing anyway.

There are many people she’s met since then who have told her something along the lines of: “Oh, wow! I’ve always wanted to write a book but never got around to it.”

Well, she also wanted to write a book but did get around to it. That’s quite an accomplishment, especially as a 15-year-old, and it’s more than most adults can say.

#2: Now she knows this about herself.

If you grow up wanting to be an Astronaut, but then you learn that it requires a ton of math, and you don’t like math, or you’re not good at it, it is not a bad thing to learn this early on, before you start taking irreversible steps toward a career path that you can’t have, or won’t like.

Finding out that you don’t want to do an activity before you make it your life’s work is a good thing.

#3: This can always change in the future.

If she ever changes her mind, she already has an Amazon Author profile, and can easily keep the story going, and sell more books to her willing audience of friends and family who bought the first one.

Or, she can write a completely new book or book series, and if that’s what she wants to do, she now knows the process, and it will take much less time the second time around because she’s done it before and knows what it entails.

I think my daughter has mostly decided not to become a writer because this process took what was her passion in life and turned it into work.

But that would happen with anybody, no matter the subject at hand: work is work, no matter what it is:

Writing is work.

Counseling is work.

Making coffee is work.

Dentistry is work.

Whatever you do for a living is work, and work is really hard sometimes.

No matter how much you “enjoy” what you do, there will always be deadlines, creative blocks, blank canvases, financial struggles, tech support problems, customer service issues, and all manner of other challenges that make it “not fun” at times.

If you’re a parent of a child, I highly recommend you give your child something hard yet rewarding to do, like this. That’s why, later this year, I’ll also be helping my youngest son, who is 11, make a comic book that he wants to sell on Amazon as well.

It will be hard work, but it’s work worth doing. And then, hopefully, he can make money at it, and decide for himself whether he wants to be a writer or cartoonist for a living or not.

It’s up to him, and I’m here for him either way.

(By the way, if you like young adult fantasy stories about pirates and mermaids, feel free to check out her book: “Ocean Eyes,” by Aja Stauffer.)