Who Killed Tucson’s Project Blue?

A fight powered by bad math, moral theater, and hysterical activism—and a preview of the AI infrastructure wars coming soon to a community near you

“Project Blue,” a proposal to build a massive data center in Tucson, Arizona, was poised to deliver $3.6 billion in private capital to the region—the largest investment of its kind in the city’s history.

It should have been a Christmas gift to the people of Tucson—bringing jobs, infrastructure improvements, and long-term tax revenue.

After years of planning and regulatory hurdles, it was ready to launch.

Then, at the very last moment, the entire project imploded in a loud and spectacular fashion—not because it failed on the merits, but because the process collapsed under the pressure of collective emotion.

Project Blue Timeline (Key Events)

This sequence matters. It shows how the public process unfolded.

June 17: Pima County Board of Supervisors narrowly approves (3–2) the land sale and rezoning required for Project Blue to proceed.

July 23: Community Information Meeting (Mica Mountain High School). The first public meeting. No vote possible. Immediate backlash and hostile public response.

August 4: Public Meeting (Tucson Convention Center). A presentation intended to inform the public before the formal council vote. Instead, it collapses into shouting and disorder.

August 6: Study Session (Tucson City Hall). Council votes unanimously to end negotiations/withdraw the annexation track (which would have enabled Project Blue to connect to utilities, effectively killing it).

Act I: The Project

What Project Blue was—and why it should have been decided on the merits

I first heard about Project Blue in June, when I was asked by The Chamber of Southern Arizona to attend a public meeting and show my support.

As a member of the Chamber’s Emerging Leaders Council, I’m looped into legislative and economic development issues and occasionally asked to get involved. In this case, the request was straightforward: show up, wear a blue shirt, and encourage the Pima County Board of Supervisors to approve the project.

(Quick note: on March 31st, Sun Corridor Inc., which had been working on Project Blue for several years, merged with the Tucson Metro Chamber of Commerce, which then began its public-facing advocacy push under its new name, “The Chamber of Southern Arizona,” ahead of the June 2025 Pima County Board of Supervisors meeting.)

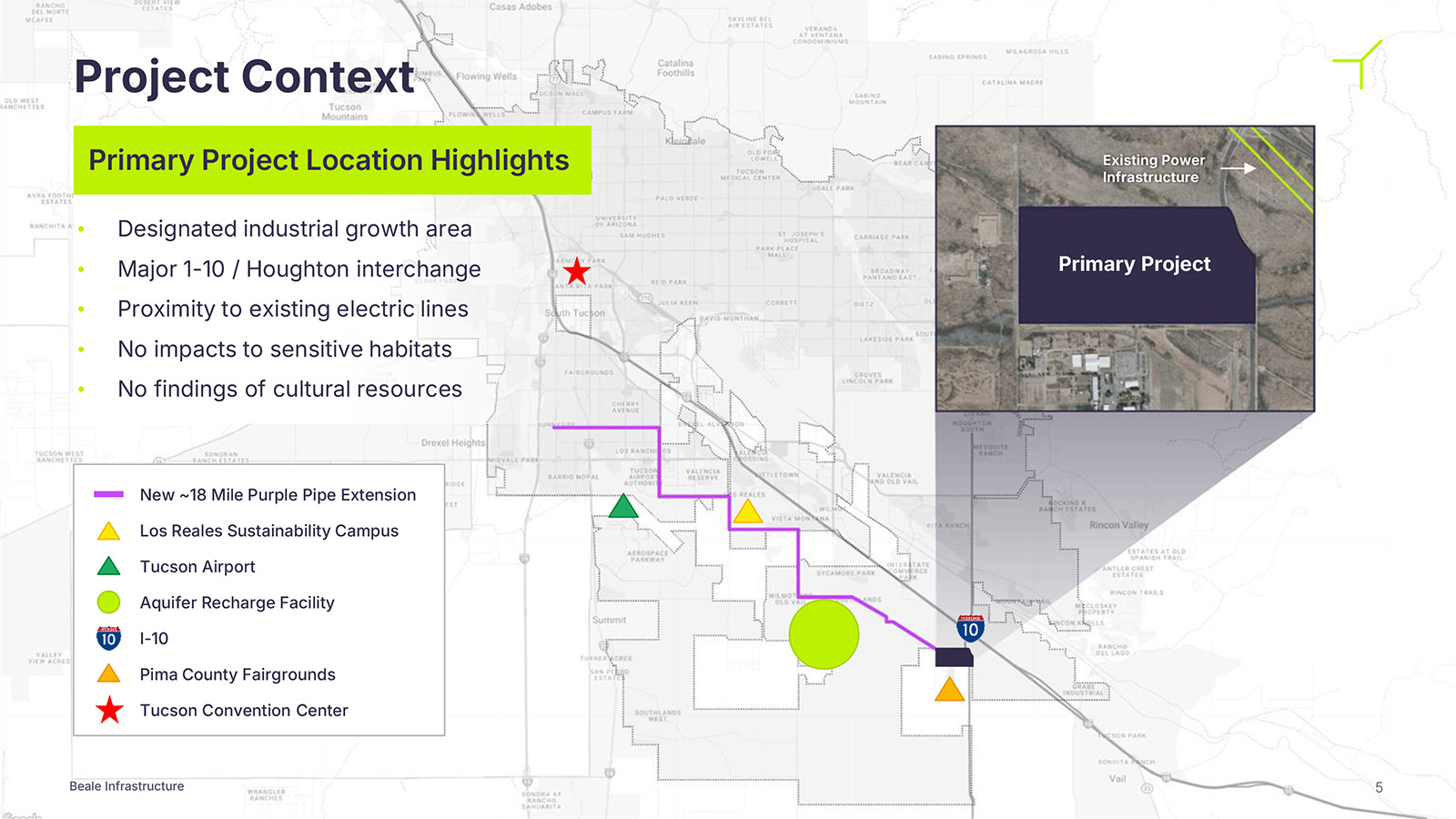

At that point, Project Blue was being described simply as a large data center project. The developer, Beale Infrastructure, had intentionally kept the end customer confidential (a common practice in projects of this scale).

None of the usual candidates for using a data center of this size (AWS, Meta, Google, Microsoft, or xAI) had been named yet. As far as most people knew, it was “just a data center.”

I reviewed the project’s fact sheet and basic details. Long story short, it was touted as “an opportunity for more than $3.6B in economic development for the City of Tucson.” That’s not a trivial number. And there was much to like:

Private funding for huge public infrastructure improvements.

A “water positive” project that would “match 100% of all water consumed with additional water replenishment projects.”

It was framed as a model for “how public-private partnerships can support responsible development of critical digital infrastructure by prioritizing community needs.”

Overall, it appeared to be a thoughtfully crafted project designed to survive years of regulatory scrutiny, built by people who clearly understood Tucson’s geography, politics, and constraints.

Project Blue resembled long-term infrastructure projects I’d seen succeed in Colorado. But in over five years of living in Southern Arizona, nothing I’d encountered had come close to its scale here.

The project involved building a new data center by the fairgrounds, just eleven miles from my house. Amazon already operates a fulfillment center right down the street from where I live—close enough that, for the first time in almost 20 years as an Amazon Prime member, I get same-day delivery instead of having to wait for two days or more.

Every time I drive south on Kolb Rd toward I-10, I’m thankful for that big, boring white building that makes my daily life meaningfully better.

Project Blue seemed to be an expansion of the responsible infrastructure in Tucson that, when done well and placed intelligently, makes everyone’s lives better. Reading through the fact sheet, it actually reminded me of Apple Park (often called “Apple Campus 2”), the recently built, updated headquarters for Apple in Cupertino.

Like Project Blue, Apple Park was an ambitious modern infrastructure project for a tech company that required considerable cooperation with the local government and multiple very complicated, very tedious steps along the way.

It also initially used NDAs to keep the identity of Apple Inc., the end user, a secret until the last minute.

It was also an enormously expensive project that infused billions of dollars in private capital into a community that hadn’t seen deals of this size before, while seeking to minimize environmental impacts. Apple’s $5 billion campus on 360 acres added fruit trees, native grasses, and an herb garden, and uses recycled water and solar power. Project Blue’s $3.6 billion campus on 290 acres would also add trees, native vegetation, and employ rainwater harvesting and solar power.

Unlike Project Blue, Apple Park was massively popular—and Cupertino celebrated it as a symbol of ambition and confidence, not something to be feared.

Tucson, as I would soon learn, reacted very differently—and not by weighing tradeoffs or asking hard questions.

Act II: The Spark

How a routine public process turned volatile

In the end, I didn’t attend the Pima County meeting. I couldn’t fit it into my busy summer schedule, it didn’t seem emotionally or politically charged, and I didn’t feel any strong personal connection to it.

After the meeting, I figured it was no big deal: the county ultimately approved the land sale and rezoning in a close vote (3-2). At the time, it seemed like Project Blue was simply moving through the normal, slow, boring machinery of local government.

And then came the meeting at Mica Mountain.

That was when everything changed—for the project, for Tucson, and for me.

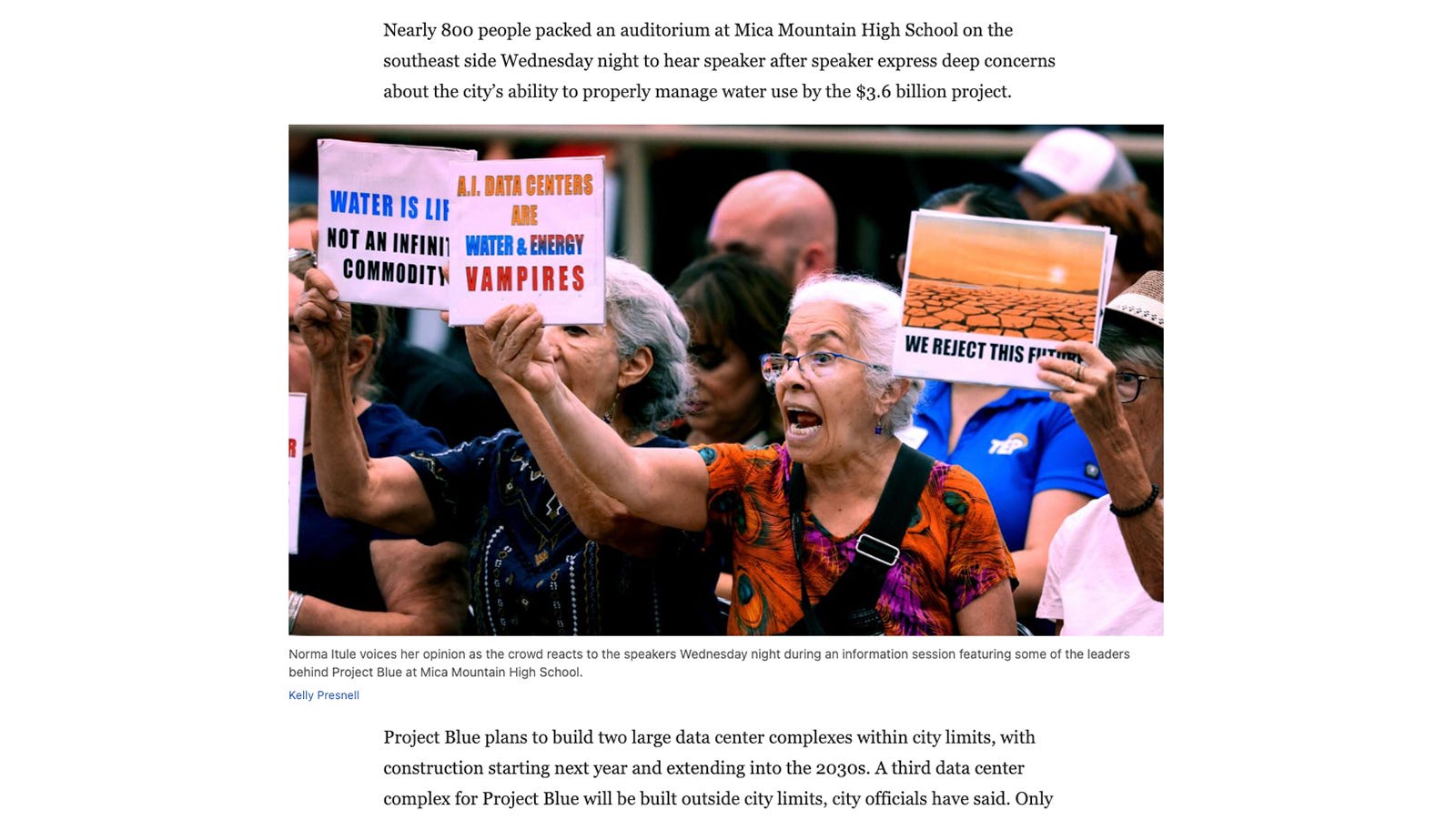

After receiving approval from the county, Project Blue’s next step was a “Community Information Meeting” at Mica Mountain High School.

I got an email from a fellow Emerging Leader who supported the project and planned to attend. She asked those of us who value economic growth and responsible development to be part of the conversation.

“Your presence can help make sure the full picture is represented,” she wrote.

That sounded good to me. I wanted to help represent the full picture, whatever that would turn out to be.

I added the event to my calendar for July 23, wore a blue t-shirt to work that day, and planned to leave the office early to make the 5:00 pm meeting—even though it was all the way on the other side of town.

My final work meeting that day, however, took much longer than expected. By the time I was done, I glanced at the clock, and it was already 5:30.

“Oh, crap, not again,” I thought. I had now missed two of these events in a row.

I knew the drive to Mica Mountain well (my youngest son used to play basketball on their campus), and I was sure that by the time I made it through rush-hour traffic, I would have missed almost all of the meeting.

“Maybe it’s not that big a deal,” I thought. “It’s a public event, so they’re probably livestreaming it. I can just watch it tomorrow.”

The next day, I kept my promise to myself to do my civic duty and watch the public meeting. I pulled up the video during my lunch break.

Nothing could have prepared me for what I saw. My jaw dropped as a wild circus unfolded on camera.

I saw very few people (almost none) wearing blue shirts in the audience, as I had planned to do. I saw a lot of orange construction vests on people seated in the audience, and many people wearing red shirts. But the red-shirted people weren’t sitting calmly; they were standing in the back, holding signs laced with profanity, and shouting “BOO!” repeatedly.

I clicked around on the video player, skipping forward and backward, trying to understand what had caused such a bizarre escalation. It was a pure cacophony of noise.

“Whoa, this is not at all what I expected,” I thought.

I didn’t want to watch this anymore. I stopped the video and started Googling to try to see what news there might be about the event. There were several stories out already—and the headlines were jarring:

Few hundred attend fiery first meeting on Project Blue, some leave with same concerns

Tucson officials, developer face angry questions as 800 pack meeting on Project Blue

Hundreds demand answers on Tucson’s proposed Project Blue data center at heated community meeting

Emotions run high in public meeting held by City of Tucson over Project Blue

What on earth had gone wrong?

Seeing all of this made me feel like missing the meeting the night before helped me dodge a bullet. The protesters looked absolutely furious, angry enough that showing up in a blue shirt, as I’d initially planned, suddenly felt like an act of provocation.

People shouted, “Yeah, right!” “We don’t trust you!” and loud boos of disapproval as the presenters tried to make their case for this marvel of modern technology and engineering.

The crowd wasn’t buying it. Attendees held signs with angry (and sometimes profane) slogans:

“WATER POSITIVE MY ASS”

“PROJECT BLUE IS A SCAM”

“CORPORATE F**KERS”

“HANDS OFF OUR WATER”

“WE ARE NOT ‘WET’ FOR BEALE”

“WATER FOR THE PEOPLE, NOT FOR BILLIONAIRES”

“NOT ONE DROP FOR DATA”

(Take note of that last line—that will come into play in a big way later.)

I didn’t know what to make of any of this, so I used a lifeline: I decided to phone a friend. I called a fellow small business owner in Tucson who is also deeply involved with the chamber of commerce, and asked what she thought.

Me: “Did you go to the Project Blue meeting last night at Mica Mountain?”

Her: “Was that last night? I heard about it but didn’t go. Why do you ask?”

Me: “I was going to go, but couldn’t. I’m glad I didn’t go, now.”

Her: “Why? What happened?”

Me: “Have you seen the news?”

I read off some of the headlines and quotes I found, trying to convey how quickly everything had unraveled. She was as surprised as I was by how much hostility had surfaced so quickly.

I told her that, of course, I want to support my community, and as a chamber member, I do feel it’s important to contribute to public conversations about how we can best build and grow our local economy.

But this?

I was now rethinking whether I should be involved or say anything at all. This did not feel like the usual opposition from vocal NIMBYs who always oppose everything. This was something altogether different.

These people were filled with rage, and now I was afraid that if I made any public statement at all in favor of Project Blue, or simply showed up wearing a blue shirt, it could make me and my business a target. I asked my friend for her thoughts.

“How do you decide where to draw the line as a business owner? How do you weigh the risks of giving public support to something that can hurt your brand? I thought Project Blue was a community-supported development, but this clearly isn’t about economics or business at all. This is pure politics.”

She commended me for being cautious and said I would have to decide this for myself. I appreciated her being a sounding board, but she was right: only I could decide whether sticking my neck out for something that had become so toxic was worthwhile.

My phone call didn’t resolve anything.

I started thinking through the potential fallout. If I had attended that meeting, and my face ended up in a picture at the top of one of those news stories, could that harm my business?

I still liked everything I had learned so far about the project based on the available data. But it was becoming clear that publicly supporting it now carried a real downside and no meaningful upside.

Project Blue wasn’t going to change my life immediately. It wasn’t going to make me rich, land me a client, or materially benefit my company in the short term. It was the kind of long-term investment that helps a community function better, even though the benefits are diffuse and take time to show up.

Despite owning a small, local business here in Tucson, speaking favorably about the project risked reputational damage, online targeting, or being reframed as a “corporate shill” for Amazon, OpenAI, or “big tech billionaires.”

Like the call I made to my friend, the meeting at Mica Mountain resolved nothing.

As a purely informational meeting, no structural changes were going to be made there anyway: people attempted to make arguments for and against the project, opinions were aired (shouted), and viewpoints collided in what quickly became a disordered and chaotic public gathering.

Since I didn’t attend, I can’t say so with certainty, but by all appearances, nobody’s mind was changed. Both sides dug into their existing positions with even more fervor than before.

What I took away from that meeting was simple: Clearly, the data no longer mattered. The conversation had moved beyond facts and into pure optics.

Act III: The Breakdown

When slogans replaced tradeoffs

The next step—the real test—was always going to be the Tucson City Council.

That’s where Beale Infrastructure would formally ask the city to annex a 290-acre parcel into Tucson’s city limits, making it possible to connect the project to public power and water infrastructure.

That vote was the final hurdle of a long, complicated, and expensive process. Before that day even arrived, the fuse was already lit.

Then everything exploded.

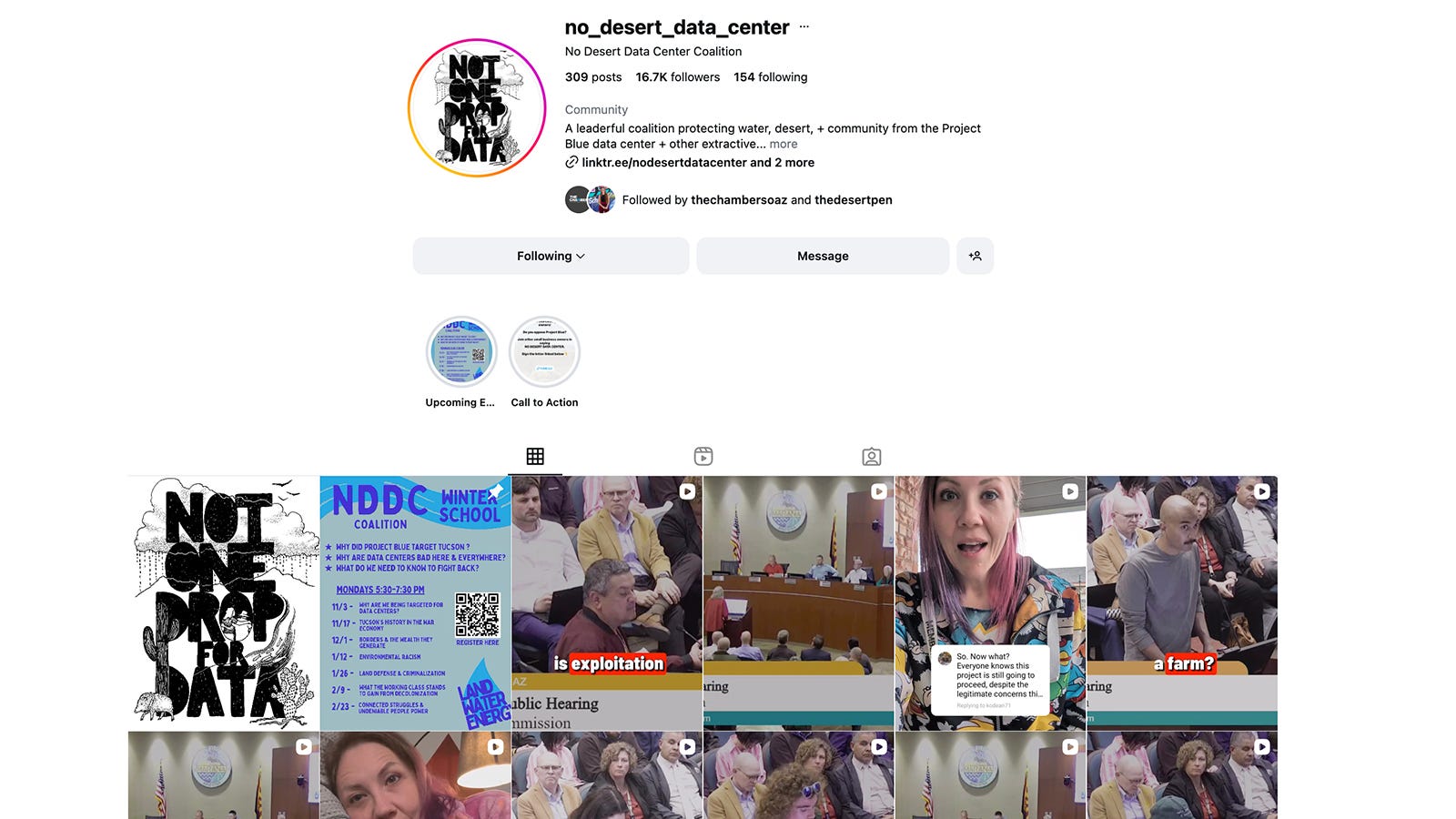

One of the biggest sticking points in opposition to Project Blue is just how late in the process public input was solicited. This clearly struck a nerve with the local activists on Instagram who created an Instagram page, put out a Bat Signal, and called in the reserves, quickly posting text messages, videos, and images on social media, asking everyone who cares about Tucson’s most precious resource—water—to engage and get involved to prevent a data center in the desert.

Stickers were quickly printed up.

Campaign buttons were pressed.

Bright red t-shirts were screen-printed.

All were distributed to activists to wear on camera.

Feeling caught off guard (and denied early visibility into a project already deep in the approval pipeline), activists shifted from persuasion to mobilization.

They put in a panicked, mad dash to stop it by organizing quickly and effectively.

And to their credit, they did.

The “No Desert Data Center” Instagram account quickly gained over 10,000 followers (as of today, it’s over 16,500) and posted regular “Upcoming Events” and “Call to Action” notices for activists to mobilize and show their opposition to any data center, for any customer, anywhere in the desert.

A local artist was quickly enlisted to create a logo: stark black text on a white background with a rain cloud, fish in a stream, cacti, and a javelina, that distilled their opposition into a simple phrase:

“NOT ONE DROP FOR DATA.”

As a slogan, this is brilliant.

Who doesn’t want to save water in the desert? Those of us who live in Southern Arizona understand, viscerally, how crucial water is for life. We don’t need a lecture on scarcity here—we see it every day just by looking out the window.

No, a pat phrase like this is very good marketing. I say that with admiration as someone who has worked in marketing for twenty years. Just five words, emotionally charged, to explain an entire movement. Brilliant.

The problem is, of course, that it collapses immediately under the slightest bit of scrutiny.

An amazing soundbite? Yes. But in practice? Pointless and dishonest.

“Not one drop” isn’t a policy position. It’s zero-tolerance absolutism dressed up as environmental virtue.

At that point, the debate stopped being about tradeoffs and became about purity—and that’s where the logic fell apart.

When you’re talking about infrastructure (of any kind), there are simply no systems that run on “zero” of anything. No public works run without tradeoffs, without inputs, or without costs.

Adult systems don’t work that way.

We already use water in Southern Arizona for all kinds of things that are largely uncontroversial: beef, alfalfa, cotton, dates, pecans, stone fruit, and other agricultural staples. Arizona is also famous internationally for its golf courses, which consume incredible amounts of water.

But I have yet to see any Instagram campaigns demanding “Not One Drop for Peaches” or “Not One Drop for Golf.” Why the strangely selective outrage for data centers?

And here’s where the lack of logic of a simple phrase like “Not one drop for data” really starts to show. It may be hard to believe unless you’ve looked into it, but Tucson isn’t using our full allotment of water.

I’ll say that again so I’m completely clear: the City of Tucson is legally entitled to more water than it currently uses. This is an established fact that isn’t disputed by anyone who knows Arizona’s water policy.

To be clear, water is indeed one of the desert’s most precious resources. But the legal compacts that govern Arizona’s allotment of water are EXTREMELY detailed and carefully monitored by multiple states, the federal government, and even a foreign country (Mexico).

We have fought our way to the United States Supreme Court multiple times over this issue: in a nearly perfect example of a system of checks and balances, there are seven states supplied with water from the Colorado River, and each one jealously guards their own interest while viciously monitoring everyone else’s usage like a hawk.

When I lived at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, where the Colorado River begins, people would sometimes say, “If you want to become extremely rich in Colorado, become a water attorney.”

All that to say, yes, water is our most precious resource. We’re already acting like it.

We don’t need activists wearing red shirts and buttons pretending like it’s a new concept.

It’s no accident that Tucson uses less water than we’re legally entitled to. This is by design, and it is the result of meticulous planning and modern technological infrastructure.

Project Blue was designed to run on excess water, non-potable water—water unsuitable for drinking or otherwise circulating back into our public water supply.

That’s precisely why the exact site was chosen, and the cooling system was engineered the way it was. That’s also why the people who literally run our water supply were supporting Project Blue.

When career city employees like Scott Schladweiler (Deputy Director of Tucson Water) are:

participating in briefings

answering technical questions

explaining water usage, sourcing, and mitigation

appearing alongside developers and county officials

…that tells you something very specific and very important: the project had already passed internal professional scrutiny. Put plainly, they had already run the numbers themselves.

And there’s an irony in all of this that the “not one drop” activists don’t seem to care about.

Tucson is not only using less water than we’re entitled to, but we also have a surplus of water that is non-potable that can either be used for some applications (like cooling data centers) or discharged and not used at all.

Currently, we’re doing nothing with it, so it gets pumped into the Santa Cruz River.

In other words, we have so much water that we can’t use it, so we just dump it out.

“Not one drop for data” feels good.

But you don’t govern a city in the desert with a million residents with good feelings.

What followed was not clarification, but accumulation.

The clearest sign that facts didn’t matter anymore came during public testimony, when City Manager Tim Thomure attempted to provide context.

The Arizona Daily Star reports:

When Tucson City Manager Tim Thomure said 17 golf courses that use reclaimed water each use the same amount of water annually as will Project Blue during its first phase of operations ending in 2029, people in the crowd shouted, ‘That’s not relevant’ and ‘that’s immaterial.’

Here’s where the story becomes frustrating for people who aren’t activists but do care about clean water and responsible environmental policy: this was never really about water.

You don’t have to take my word for it. Just watch how the activism expanded over time.

It began with water.

“Not One Drop for Data” was the mantra in the beginning, which was clear enough.

It was also about animals.

Habitat will disappear and harm the yellow-billed cuckoos. See the desert tortoises who will be displaced? Here’s a drawing of a dead Gila topminnow. Do you want these little minnows to die?

It was also about secrecy.

Who is the secretive tech company behind the mysterious Project Blue? Is it Amazon, Google, Meta, or OpenAI? Why won’t they tell us? What do they have to hide?

It was also about electricity.

Where are the guarantees that this data center’s power usage won’t raise our rates? And by the way, data centers burn coal for power!

It was also about billionaires.

Look at Jeff Bezos slurping up a river with a straw. “Water for the people, not billionaires.”

It was also about Amazon.

Amazon is an evil global company that puts local companies out of business! Amazon does not care about our community!

It was also about AI.

Data centers will power the AI that’s going to steal our jobs and put us out of business!

It was also about Donald Trump, ICE, and Palantir.

Data centers power Palantir and secretive facial recognition, which is helping Donald Trump use ICE to harass and kidnap immigrants. A vote for Project Blue is a vote for ICE!

It was also about organized labor.

Amazon has a history of being anti-union! Where are the promises for union jobs in Tucson?

It was also about progressive values with words I’ve never even heard before.

“Environmental racism?” “Sacrifice zones?” and “Data colonialism?” (Yes, really).

In other words, it was about everything and the kitchen sink—all unrelated national culture-war issues… under the guise of saving water.

That isn’t mission creep. It’s a movement in search of a justification.

Act IV: The Consequences

How Tucson rewarded the wrong behavior

None of the protesters had any formal power, of course. Whether Project Blue would move forward was up to the Tucson Mayor and City Council, who alone had the authority to annex the land—thereby connecting the proposed data center to the city’s power and water.

This final step was the most consequential of all, making the difference between a bare patch of desert in unincorporated Pima County and a functioning piece of critical infrastructure capable of generating jobs and tax revenue for the City of Tucson for decades to come.

After multiple years of planning across jurisdictions, coordination between governmental agencies, and review by experts across numerous domains, representatives from Pima County, Beale Infrastructure, and a long list of additional stakeholders were finally prepared to speak when it mattered most.

That process was expected to culminate in early August.

On August 4, the City Council held a public meeting intended to present the details of Project Blue, answer questions, and prepare councilmembers for a formal vote two days later.

In theory, this was where the facts would be laid out calmly, tradeoffs discussed openly, and decision-makers given the information they needed to govern responsibly.

That is not what happened.

If ordinary citizens hoping for clarity were expecting the public meeting to finally provide answers we could trust, we were sorely disappointed. I certainly was.

From the very beginning, the event collapsed into disorder.

As Arizona Luminaria reported:

A particularly boisterous group of teenagers repeatedly stood on their chairs, held signs high above their heads, and screamed themselves hoarse in forceful disapproval of any claim in favor of Project Blue. ‘Allow them to introduce themselves so we can hear what they have to present,’ Tucson spokesperson Andrew Squire beseeched the crowd. ‘You can still boo your hearts out afterwards.’

I urge you to read that again.

This was not a normal public meeting in any meaningful sense. There was no pretense of decorum, deliberation, or good faith. It was a chaotic spectacle—one where volume and intimidation replaced discussion.

City representatives were reduced to begging the crowd to allow presenters to speak at all.

That moment mattered far more than any slogan or sign. It demonstrated—clearly, publicly, and on the record—that the basic conditions required for deliberation no longer existed.

By the time the meeting ended, the outcome of the upcoming council meeting was already effectively decided—not by facts, not by tradeoffs, but by intimidation.

This wasn’t a democratic decision made after deliberation; it was a textbook heckler’s veto, where the ability to disrupt replaced the obligation to govern.

Two days later, everything crashed and burned.

The event earlier that week had already condemned it to death; the execution came swiftly at the council meeting and “Study Session.”

Not with a debate.

Not with a vote on the merits.

And not with any serious weighing of tradeoffs.

On August 6, following the public meeting that had collapsed into shouting and disorder, the Tucson Mayor and City Council convened again in a Study Session.

But instead of proceeding with a substantive discussion of annexation, where the project’s costs, benefits, and tradeoffs should have been debated, the council took a different path.

Council voted unanimously to end negotiations and pull the annexation/development agreement from consideration, meaning there was no merits vote on Project Blue.

There would be no deliberation.

No structured argument for or against the project.

No public weighing of costs and benefits.

Project Blue was not rejected after a fair debate. It was never truly debated at all.

I wasn’t in the room for the city council meeting. By that point, I had grown weary of the hope that any good-faith discussion was still possible, and I gave up on even planning to attend any public meetings at all—no matter what color shirt I might wear.

Everything leading up to that night had felt pointless and embarrassing. Months of taxpayer-funded process had devolved into performative kabuki theater rather than civic deliberation, with no meaningful dialogue about what Project Blue actually was, who stood to benefit, or whether compromise or negotiation was even on the table.

But I did watch some of the meeting—at least as much of it as I could stomach.

What happened that evening shocked me.

When the council’s decision became clear, and it was understood that Project Blue was effectively dead, the room erupted. Cheers. Applause. Shouts of celebration. People hugged. Some cried tears of joy.

I later watched a video posted on Instagram by the “No Desert Data Centers” group showing the moment the Project Blue delegation stood up and exited the room.

city council ending project blue and watching beale take the walk of shame!!!

It was hard to comprehend what I was seeing.

The people leaving weren’t storming out. They didn’t yell, or gesture, or complain. They stood up quietly—smiled—politely gathered their briefcases, and exited without incident.

I recognized at least one person taking the “walk of shame.” Some of these people lived in Tucson. Some of them worked here. Some were public servants who had spent years doing their jobs in good faith.

And the crowd went wild—as if they’d just expelled a foreign invader.

That was the moment something in me shifted.

For the first time, I felt not just confusion or disappointment, but actual disgust.

In Tucson, it seems, no good deed goes unpunished.

A broad coalition—including civil servants and professionals across multiple disciplines—had spent thousands of hours attempting to bring a major investment in technology, infrastructure, and jobs to Southern Arizona. They carried the football all the way across the field, only to fumble it at the 1-yard line.

The activists were so very proud of themselves.

So very proud of what they had stopped that day.

So very proud of the message they had sent.

They don’t realize that their message was not: “In Tucson, we protect our resources.”

Their message was: “Tucson is closed for business.”

As it stands today, Project Blue, in its original form (becoming annexed into the City of Tucson and connected to the City’s power and water), is dead.

Beale Infrastructure remains the purchaser of the land, but the City’s decision to withdraw from annexation means the project—whether modified or re-tenanted—will proceed, if at all, outside Tucson’s boundaries. As a result, Tucson has now forfeited the associated tax base, infrastructure investment, and any leverage over water sourcing, design standards, or long-term economic impact.

So, in a highly ironic twist, Tucson technically didn’t stop the project—it just removed itself from it. By choosing not to annex the land and connect a major revenue-generating facility to city-owned power and water, Tucson gave up its only real leverage: a seat at the table.

The outcome is stark. No negotiated oversight. No infrastructure upgrades. No tax base. No public benefit. The city declined participation in a deal that may still generate substantial value—only now, Tucson receives none of it.

Beale Infrastructure is also exploring building other, similar projects in nearby jurisdictions (which is a detail that will matter later).

So, with activists dancing on its grave, how can we take an accurate autopsy? Not just of Project Blue, but the entire process, from start to finish?

This is important because the most concerning part about the death of Project Blue is not what happened, but how it happened.

What, precisely, were the lessons learned from this?

For the City of Tucson and outside investors, this will take time to discern. Projects this large move slowly, and so much happened so quickly toward the end that it’s hard to even understand the sheer scope of it all, and how it affects all the players involved.

The whiplash and the bruises will certainly be felt for years.

But the lesson Tucson learned was grim—and potentially dangerous.

To wit: the protesters and activists learned the worst lesson they possibly could:

“If you shout loud enough, you will be rewarded.”

By letting a few hundred angry activists derail a multibillion-dollar project that took careful thought and consideration for years, they now feel like they’ve been enabled.

It worked.

They won.

Like a toddler rewarded for screaming at the grocery store, the message was clear: escalation works. Tucson taught her babies that all they must do is scream loudly enough, and they’ll be rewarded with exactly what they ask for.

Red-shirt activists can safely conclude in the future that if they just show up to a few public meetings and overwhelm the process through noise and intimidation, they can shut down debate and cow their officials into voting “No” unanimously, even with billions of dollars on the line.

In fact, as the debate intensified, some of the pressure surrounding Project Blue moved far beyond public forums. More than one person directly involved in the process later reported receiving harassment and threatening messages—an escalation that fundamentally changes the conditions under which public decision-making can function.

This shameful shutdown and cancellation tactic has been used quite commonly across the nation on college campuses, and unfortunately, Tucson just showed that it can be used successfully off campus as well—even at City Hall.

To phrase this as a stark warning: the wrong people were emboldened to use the wrong tactic, which was exactly the wrong outcome, regardless of whether Project Blue was a good idea or not.

I’m not a Tucson native. I’ve lived in California, Colorado, and most recently, Arizona. Not being from here gives me a level of detachment that is valuable in cases like this. Rather than being “defensive of my homeland” and feeling territorial, I have the benefit of diagnostic framing as an outsider.

I don’t even have to answer ludicrous questions like: “But don’t you care about how Project Blue is bad for Tucson?” since, as I mentioned, many, if not most, of the people involved in putting it together were (and are) public servants who are from Tucson, live in Tucson, and even literally work for Tucson.

I feel they have done a superb job at addressing those questions ad nauseam with real, substantive answers. I am satisfied that the framers of Project Blue already considered every single one of those concerns, filtered them through experts, performed feasibility studies, and employed numerous mitigative strategies to allay—or at least address—the concerns of all the parties who actually know what they’re talking about.

In fact, Tucson City Council Member Nikki Lee, who represents Ward 4 (where I live), even posted a spreadsheet online listing 111 questions about Project Blue.

Every single one of those questions was answered in great detail.

But none of that matters when nobody cares about facts. In a dispute, facts only matter under the assumption that you’re working with rational actors, and this was not the case.

None of what happened in the dispute over Project Blue was rational.

What did happen—clear to outside observers—was a catastrophic failure in a microcosm, with worrying potential for escalation and portability.

In other words, what happened in Tucson should not be understood as a quirky local controversy or a one-off civic meltdown.

It should be understood as a successful test.

A relatively small, highly motivated group of activists discovered that they could derail a multi-billion-dollar infrastructure project not by winning an argument, not by persuading the public, and not by defeating the project on its merits—but by overwhelming the process itself.

They didn’t need a majority, expertise, or facts.

They didn’t even need coherence.

They just needed volume, visibility, and the willingness to escalate without consequence.

And it worked.

That’s the part that should concern anyone paying attention because nothing about Project Blue was unique to Tucson.

Not the technology: data centers exist all over the place and have for decades.

Not the scale: many, much larger data centers already exist.

Not the public-private structure: this is common enough all over the USA.

Not even the desert, for Pete’s sake: Phoenix has lots of data centers, and it’s even hotter there than it is in Tucson.

And certainly not the fears that were weaponized against it: Luddites and environmentalists constantly beleaguer building and development everywhere it exists, always.

What was new was the speed at which narrative panic overtook institutional process—and the ease with which elected officials discovered that the path of least resistance was to simply make the problem disappear.

No vote.

No debate.

No tradeoff analysis.

No accountability.

Just retreat… then, “Poof!” it’s gone.

The biggest outside investment in Tucson’s history, years in the making, was derailed.

In just 50 days.

That is not a local failure.

That is a tactic that’s easy to replicate anywhere.

Before any of the disastrous public meetings were held, I was warned about the symbolic importance of Project Blue by an octogenarian in Tucson’s real estate community—someone deeply concerned that Tucson was about to drop the ball yet again.

As I learned, Tucson has a long and storied history of shooting itself in the foot through apathy and even outright hostility toward companies wanting to relocate, invest, and build here. These stories go back many decades, even into the 1960s.

Residents may remember 2013, when, long before I moved here, Grand Canyon University proposed building a $100 million satellite campus at El Rio Golf Course on Tucson’s west side. The numbers were solid: up to 1,000 jobs, 6,000 students, a $60 million annual payroll.

The opposition was mobilized, and “Not In My Backyard” won the day. GCU went to Mesa instead and built a 160-acre campus.

It’s not just institutional relocation or expansion, either—there’s a bizarre hostility toward internal development intended to build up Tucson from the inside as well.

In 1984, Pima County voters rejected a bond measure for the Rillito-Pantano Parkway, a 13-mile east-west route backed by business and development leaders. Similar transportation proposals failed in 1986 and 1990.

The net result? Three strikes, and you’re out: Tucson remains one of the only major American cities without a crosstown freeway.

This distinction costs commuters time every single day and businesses millions in productivity every single year. And it’s highly ironic to hear that the same residents whose favorite pastime is cursing the poor condition of Tucson’s famously pockmarked streets, bursting with more traffic than they were ever designed to hold, had a chance to fix this problem and said no.

Three times in a row.

Project Blue wasn’t an aberration. It was an echo.

The net effect is that Tucson is becoming famous not for what it wants or supports but for what it does not want and does not support.

This pattern stretches back more than forty years. And here’s the thing: capital has memory.

Project Blue was a magnificent opportunity to at least say, “We welcome the idea. No guarantees, but let’s hear them out.”

Yet, once again, the message sent was unmistakable: your money is not welcome here.

Tucson will not feel the consequences immediately. Capital doesn’t react overnight. The damage shows up quietly—when fewer proposals arrive, when ambitious projects die during exploratory calls, and when site selectors simply stop putting Tucson on the list.

They won’t announce it with a press release.

They won’t argue with activists.

They’ll just move on and shake the dust off their feet when they leave our town.

I know a lot of Tucsonans will say, “Good! We like it that way.”

They insist the city doesn’t need outside investment. Tucson can thrive without it. But follow their logic to its conclusion—what IS the ideal economic makeup anyway?

Data centers? = Corporate greed.

Amazon? = Evil tech billionaires.

Defense contractors like Raytheon? = War profiteers.

Davis-Monthan AFB? = Military-industrial complex. (Also, Israel/Palestine).

Cross them off the list, and what’s left of our economic base? A university, and a thousand food trucks. Whoopee. Tucson will make its mark as a UNESCO City of Gastronomy and the birthplace of the chimichanga, and they think that’s good enough.

But they are wrong.

A metropolitan area of more than a million people cannot run on vibes forever.

What happens next is predictable. These projects don’t disappear.

They relocate.

Act V: The Lesson

Why this won’t stay in Tucson

Before looking at where these projects go next, it’s worth understanding why this tactic worked—and why it will work again.

There’s a scene in The Godfather: Part II that I think about all the time. It captures something most people don’t understand about power, and it fits perfectly here.

Michael Corleone travels to Cuba to finalize a massive deal with Hyman Roth. Enormous sums of money have already been spent buying influence: paying off politicians, bribing police, and securing protection. The syndicate believes it has locked everything down.

They believe they own the island.

Then, almost incidentally, Michael witnesses something unsettling: a communist revolutionary hops into a cop car with a live grenade in his jacket, killing both the police officer and himself in the process.

There is no negotiation, payoff, or leverage. Just pure conviction.

Michael is visibly shaken—not by the violence (he’s certainly used to that), but by what it implies.

Corleone: “The soldiers are paid to fight. The rebels aren’t.”

Roth: “What does that tell you?”

Corleone: “They can win.”

He realizes his side has spent a fortune trying to control outcomes with money, while the other side is willing to fight for free. Worse, they’re willing to die for their cause. The entire power structure he assumed was stable is suddenly upended and looks fragile.

No one else grasps the significance of what happened. Only Michael does—and almost by accident.

In the next scene, Hyman Roth, unfazed, boasts, “Michael, we’re bigger than U.S. Steel.” He’s convinced that their money, scale, and institutional control make them untouchable.

Yet within days, the Batista government collapses anyway. The regime didn’t fall because the revolutionaries were stronger on paper—it fell because they were willing to escalate without limit.

That’s the lesson Michael learns too late: When one side is constrained by norms, process, and reputational risk—and the other side is willing to escalate endlessly at no personal cost—traditional power structures stop functioning.

Not because they’re evil, but because they’re outmatched.

(To be clear, this is not an analogy about violence—it’s about the asymmetric commitment where one side is constrained by process, reputation, and institutional norms like “politeness.” The other side can afford to escalate indefinitely at no personal cost.)

Tucson didn’t lose because the protesters had better data, better plans, or better arguments. It lost because escalation beat deliberation.

Once that lesson was learned, the fight was over. Not because the argument was settled—but because the rules of engagement had changed.

And that’s why the same protest, with the same slogans and the same demands, has already started reappearing in other cities outside of Tucson: Marana, Chandler, and Eloy, to name a few.

As I write this, Beale Infrastructure is pitching a modified version of Project Blue to smaller communities on the outskirts of Tucson.

The Town of Marana (population ≈ 62,000—roughly one-tenth the size of Tucson) is in discussions with Beale about a different version of the data center. This time, however, it’s an air-cooled facility that does not use water the way Project Blue would have, as originally proposed.

Great, right?

By the logic of the “Not One Drop for Data” protest, an air-cooled facility should resolve the water objection entirely and settle the matter for good. It’s a different design, in a smaller town, 43 miles away from the original site.

It’s also worth noting that Marana’s Planning and Zoning Commission has, so far, run a tightly structured public process that allows for broad participation without the kind of disruption seen elsewhere.

So this should be a win-win. Everybody should be happy now, yes?

No.

Not even close.

Once again, the “No Desert Data Center Coalition” turned on the Bat Signal, calling for protesters to activate:

Let the Marana Town Council know that voting for a hyperscale data center this size is a horrible idea and that you’re against it BEFORE their meeting on January 6th

PACK THE MARANA TOWN COUNCIL MEETING ON 1/6!

#nodesertdatacenter #notonedrop #maranaaz #desertlife #tucsonaz

But why? We solved the water problem, right?

No. The “water problem” cannot be solved.

When they say “not one drop,” they mean not one drop, anywhere, ever.

Changing the technology from water-cooled to air-cooled doesn’t resolve the objection at all.

How? Through logic that can only be described as… incredibly creative:

An air-cooled facility uses more energy, and since our energy companies like TEP rely on fracked gas for their mix, this has water implications: more demand for fracked gas means more water used in fracking it, and more water lost in generating steam for the fracked gas plant.

If this were a legal fight in a courtroom, an attorney might call this a “novel legal theory.”

This will take a moment to explain, but bear with me.

With Project Blue, the argument (at first) was simple: “Data centers use too much water.” Now, in Marana, the argument has evolved into:

Even if they don’t use water on site, they use energy.

Energy comes from fracked gas.

Fracking uses water.

Steam generation uses water.

Therefore, air-cooled data centers still “use water.”

See how that works?

Everything that exists on Earth uses water somewhere in its supply chain. Data centers exist on Earth; therefore, they use water.

By expanding the definition of “water use” to include every downstream input of modern energy systems, the objection ceases to be about this project at all.

By that logic, we should also be saying:

This Town Council meeting uses water.

Sipping from my water bottle before I speak uses water.

This Instagram post uses water.

Driving my car home from this meeting uses water.

Opposition to data centers has now become unfalsifiable.

When every possible configuration is unacceptable, the position is no longer about mitigation. It is about prohibition.

And you cannot negotiate with prohibition.

Regrettably, a permanent protester class in Tucson has now been activated.

With social clout as a reward and a following that needs to stay entertained, they will go in search of something to protest against.

Like Deadheads hitting the road to follow their favorite band on tour, these activists are promising to follow any data center to the ends of the earth (or the ends of the desert, at least).

Once you understand this dynamic, the outcome becomes predictable.

The projects don’t disappear. They don’t even slow down.

They simply go where escalation doesn’t work.

As we’ve already seen, these tactics don’t work so well in Phoenix—home to well over 100 data centers. Many of which use water. Right here in the desert.

Yes, Phoenix, our big brother that Tucsonans love to sneer at. Phoenix gets it.

Already one of the fastest-growing metro areas in the country, it’s becoming a megalopolis of talent, capital, and, yes, they even have vibes, too (you don’t have to choose, after all).

Phoenix says yes. Phoenix builds. Phoenix absorbs the growth that Tucson says no to.

And Tucsonans say, “So what? Good for them. We’re not Phoenix!”

Folks like this are going nowhere, and they’re thrilled to death about it.

But Tucson’s losses are a win for lots of places—not just giant cities in the Valley.

Within days of Project Blue collapsing, a similar data center project was announced in a location far smaller and far less metropolitan than Phoenix.

Wyoming.

Yes, tiny, rural Wyoming.

An entire state with a population roughly half the size of metro Tucson’s, with fewer resources and harsher conditions.

Wyoming said yes, where Tucson said no. Their governor even welcomed it loudly and publicly:

This is exciting news for Wyoming and for Wyoming natural gas producers – and it highlights the kinds of projects we can achieve through continued trade missions…

Wyoming didn’t win because it had more water, power, or sophistication.

It won because it was willing to decide.

Tucson chose to retreat without a fair vote, without a true debate, and without a real tradeoff analysis. Just silence, withdrawal, and applause.

And that applause will echo and haunt Tucson for years.

So, who killed Tucson’s Project Blue?

Project Blue was killed by activists who learned that escalation and intimidation work—and by elected officials who proved them right.

Author’s Notes

Author’s note (updated January 5, 2026): After this piece was published, several individuals with direct knowledge of Project Blue reached out to provide additional factual context and clarification. The article has been updated accordingly to improve accuracy and nuance. The central argument and conclusions remain unchanged.

City of Tucson Website

At the time of writing, it appears that most (if not all) official FAQs, briefing materials, and documentation related to Project Blue have been removed from the City of Tucson’s website. Whether this was intentional or incidental is unclear. However, given that these materials were produced as part of a public process, their disappearance is notable and troubling. Archived versions remain accessible via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine here: https://web.archive.org/web/20250916155323/https://www.tucsonaz.gov/Government/Office-of-the-City-Manager/Project-Blue-Information (Snapshot date: 09/16/25)

On Sources and Coverage

I often disagree with Arizona Luminaria’s editorial perspective. That said, it provided the most thorough, on-the-ground reporting of the Project Blue process and meetings. Several firsthand descriptions and direct quotations cited in this piece come from AZ Luminaria’s coverage, which—regardless of viewpoint—was detailed, timely, and substantively useful. Readers who value local, independent journalism may wish to support their work here: https://azluminaria.org/membership/.

The “Not a Drop” activists learned well from their compatriots who organize and protest everything since 2020. These are no doubt some outside influencers and big $$ involved and they aren’t going anywhere. As long as local governments continue to cave to their demands, small minds will prevail and Tucson will be as stymied in growth as El Paso is. The protests in El Paso shut down a voter-approved arena build that would have brought millions in revenue to the city in conventions, concerts and major sports events. But they had to knock down a few ancient “historic”buildings that nobody cared about before the vote was passed on the arena. Now the arena is dead and the dilapidated buildings sit as they always have with no plan for their renovation or removal. Yay! You idiots won!! El

Paso will continue to be the location that nobody goes to on purpose.

Ron, I have no dog in Tucson's fight, since I live in Florida, but I read every word with great interest. You have captured much of the heart of the issue. It's not about water. It was never about water. Drops of water had nothing to do with these protests. These activists are members of the same family as the masked hoodlums who try to intimidate ICE, and Seattle, and Portland City Councils. The only difference is they are not wearing masks, blowing whistles, or using violence, yet. When people act this strongly and vehemently, without any attempt to listen, evaluate, or even persuade, they are not part of a movement, but are part of a religion. This is the Social Justice Warrior Religion. They cannot win based on logic, reason, and evidence. They are incapable of persuasive argument, because they have no actual facts on their side. They are religious zealots chanting "I believe this way, and that settles the matter. All that is left is for me to bend you to my will by screaming my mantras and slogans so loudly that you lose your heart to do the right things." They cannot persuade. All they know is battle. They are the modern American Jihadis, except without the violence (for the moment). So, there are 16,000 members on their notification list? Hmmm... It would be so interesting to get ahold of that distribution list and do a quick AI analysis of their demographics; political party, other organizations in which they participate, their actual religions (or lack thereof), whether they are married with children, what percentage of them hold real jobs with real-world productivity, how many are business owners...? I also wonder if there are examples of similar communities, with this similarly motivated screaming mobs, who have figured out how to give them a chance at having their say, then closing debate, then holding the City Council vote, and deciding in favor of the project the Social-Jihadist Mob opposes?