The ‘Luck of the Irish’ Isn’t Luck: It’s the Result of Hard Work

Throughout history, the Irish have actually been quite “unlucky”

On Sunday, as I celebrated Saint Patrick’s Day for the 38th time in my life, I spent a lot of time (as I always do) thinking about the holiday, about Ireland in general, and about what it means to be Irish.

Of course, as an American, this is a huge topic with lots of nuance and emotion and involves complicated questions about ethnicity, loyalty, and… lots of other things I couldn’t possibly address here, so I won’t. (Some anti-American racists in Ireland have called me some very nasty things online, but that’s a topic for another time).

But I will address one specific aspect that was really impressed upon me during this particular St. Paddy’s Day weekend: entrepreneurship. That might sound like a stretch, but bear with me.

My name is Ronald Paul O’Ronald Stauffer. One side of my family is Irish, and the other side is German. While I have an Irish middle name, I obviously have a German last name, and that’s all most people who hear my name notice about me.

“Hi, I’m Ron Stauffer.”

This is what I say when I thrust out my hand and greet new people in a business context. And that’s what people see and hear: Stauffer, the German side.

That part of me, the “Germanness,” is obsessed with excellence, being calm and serious, tracking data, making calculations, and precisely engineering the heck out of everything to make good things great and make great things even greater.

Germans are famous for that. The stereotype is real, and I’m okay with that. I’ve always known this, and I’m proud of it.

I have intentionally embraced my German side over the years; it’s why I named my company “Lieder Digital.” I want my marketing clients to know that I care about excellence, being serious, tracking data, making calculations, and precisely engineering the things I work on (for their benefit).

But for the past decade or so, I’ve started wondering: “What about the Irish side?”

What does my being partially Irish have to do with the work I do today, the company I run, the clients I have, and the skillset I’ve developed over the years?

This has puzzled me for years. Aside from my company’s colors (my office is adorned with green, white, and orange, taken from the Tricolour—the flag of the Republic of Ireland), I couldn’t exactly figure out where Ireland or “Irishness” fits into the greater story of my values, my company, and the work I do.

Until this Sunday.

This St. Paddy’s Day, I think it finally started to make sense for the first time as I sat in my backyard, drinking a pint and pondering it all.

The German side of my family, the Stauffers, were Mennonite. Famously “plain” in dress, manner, and lifestyle, they came to America from Switzerland when America was still just “the British colonies.”

For over 250 years, they were born, lived, and died, all within a 50-mile radius. They dressed like each other, looked like each other, and sought conformity in all they did. They lived insular lives in a closed community and were, for the most part, farmers.

What does this have to do with my business? It’s illustrative of my family’s work history.

It means that for three centuries, the Stauffers have had a culture of fitting in, doing what you’re told, working hard (think: “Protestant Work Ethic”), being good at what you do, and not making waves.

So it shouldn’t surprise me at all that my dad worked for the same employer as a medical salesman for 20 years.

Or that my Grandpa Stauffer was a pilot in the US Air Force for 12 years, then worked as a salesman for Xerox for something like 30 years.

Or that my Great-Grandpa Stauffer worked as a machinist his whole life.

Or that my Great-Great-Grandpa Stauffer worked as a pants-presser and tailor for his whole life.

The way the German side of the family made a living was:

Learn a skill set

Find an employer

Get a job

Stick with it for as long as you can

It’s pretty simple, and it worked pretty well for most of them. (Come to think of it, Germany still seems to work this way today, for the most part.)

My mom’s family, the Siecherts, are also German. And the same is true for them: many of them got “steady” jobs—almost all of them are doctors or school teachers, working the same careers (often for the same employers) for decades.

But not for me.

For so many years, I’ve wondered: “Why do I have such a hard time doing what the other men in my family did? Why couldn’t I just get a normal job with a normal employer like they did and put in a normal shift and go home at a normal time?”

It’s weird: I’m self-employed, and this is dramatically different from the “normal” path listed above. It wouldn’t make sense to most of the men in my lineage. They had no idea what self-employment is like. They worked “steady” jobs for normal employers their whole lives.

Most of them never started a business. They don’t know what it’s like to wake up on a Monday morning and have that terrible realization entrepreneurs have from time to time:

“I have no money in the bank, and there’s no paycheck coming in on Friday. I’ve got to figure out how to make money magically appear by the end of the week so my wife can buy groceries.”

I’ve often wondered why it is that I seem to have this entrepreneurial spirit, why this kind of uncertainty doesn’t really scare me, and how I’m somehow always able to pull a rabbit out of a hat before the week is out. We’re always able to thank the Lord for our food on Friday evening at the dinner table. Where does that come from?

On this St. Paddy’s Day, I had an epiphany. I finally figured it out.

IT’S THE LUCK OF THE IRISH!

That kind of entrepreneurial fire clearly comes from somewhere, but it isn’t the German. It’s the Irish side!

All those stories I heard about my Irish great-grandfather are starting to make sense now. The family lore I heard at the dinner table since I was “just a wee lad” is starting to look like little jigsaw-cut pieces that are now finally putting the puzzle together so I can see the completed image.

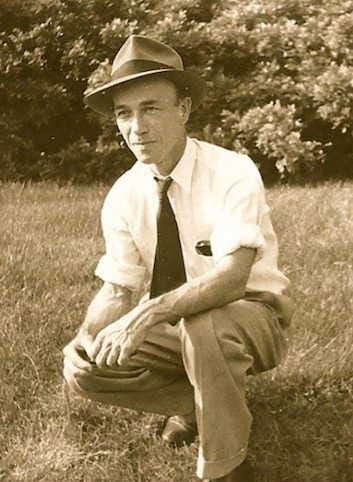

Peter McElwee, my father’s mother’s father, was a short, thin man that we called “Pop-Pop Pete.” And boy, if you want to talk about “luck,” he was born with none of it. He made his own luck out of thin air, just like I try to do still to this day.

The circumstances surrounding his birth are murky, to put it mildly. With the help of a professional genealogist, we’ve tried to piece it all together, one fact at a time, to try to make it make sense.

He was born in the dirt-poor coal mining town of Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania. He had an older brother, Thomas, that we know absolutely nothing about, a younger brother, John, we know a little bit about, and a younger sister, Margaret, who died in infancy.

As a child, he would sometimes come to the dinner table and ask: “What are we having for dinner tonight?” and his mother would tell him: “We’re having ‘Skip’ for dinner.”

“What’s Skip?” you may ask.

“Skip” was Delia Grady McElwee’s way of telling her son: “We’re skipping dinner; we can’t afford food tonight.”

Now, for some reason we still can’t fully understand, when Pop-Pop Pete was around 13 years old, he was kicked out of his house along with his younger brother. They moved in with distant relatives in another part of Pennsylvania, and the husband told them something like:

“You may live in my house, but you are not my sons. I don’t ever want to see you in my home.”

So, according to family tradition, they came home late at night and left early in the morning, coming and going through a window or side door so the man of the house never had to see them in his home.

Fast forward just a year or two, and Peter McElwee moves from Mount Carmel to Philadelphia because that’s where all the work is.

He becomes a completely self-taught electrician. But he’s just a child: 14 or 15 years old and a school dropout. So, what’s he going to do?

Pop-Pop Pete was a genius. Here’s what he did.

He finds an electrician who is an older man and goes to “work” for him in the most delightfully devious way: he gets a job as an apprentice electrician but realizes he knows almost everything he needs to do electrical work by himself.

So “his boss” sends him to a customer’s home, where they’ve requested some electrical work in the attic to be done. Like a magician or a black-belt martial arts master, Peter the Entrepreneur pulls off a magnificent illusion.

Peter: (Rings doorbell) DING DONG…

Housewife: “Hello? Can I help you?”

Peter: “Good morning, ma’am; my name is Peter, and I’m here to do the electrical wiring?”

Housewife: “EXCUSE ME?! YOU?! You’re just a child! You MUST BE JOKING!”

Peter: “Very sorry, ma’am, I misspoke. I meant to say, ‘I’m here to set up your attic for my boss to come do the electrical wiring.’”

Housewife: “Ah, yes, well, in that case, let me show you upstairs…”

An hour goes by…. there are ladders and lamps and wiring all over the place. The nervous housewife assures herself that this little teenage boy is just prepping the site for the “real” electrician to come do the work. Another hour goes by.

Peter, the Entrepreneur, springs into action again.

Peter: “Hello, ma’am, we’re all done now. Here’s your final bill.”

Housewife: “Wait, what? The work is done? How is that possible? I never saw your boss around here…”

Peter: “Really? Wow, that’s weird. He was definitely here, though, ma’am. All the work is done. Surprised? I know; he is just that good. He popped in and out super-fast, got it all done, and left for his next job.”

Housewife: “Are you sure? I never heard anyone come through the door or ring the bell…”

Peter: “Yeah, wow, again, that is really weird. Anyway, ma’am, about that bill…”

This man—this very young man—was brilliant. He lived and stayed in Philadelphia for the next few years, working as an “apprentice” for his mysterious, invisible boss that nobody ever saw.

Eventually, he married, had two daughters and one son, and ended up in a horrible marriage, getting an “Irish Divorce,” never legally divorcing, but living separately from his wife. As he got older, jobs got harder and harder to find: he was in his 20s during the Great Depression, but Peter the Entrepreneur once again pulled another rabbit out of his hat.

The employment lines were filled with hordes of older, more eligible men with deep skill sets, lots of experience, and better resumes than he had.

Peter, the Entrepreneur, has a better idea. Rather than standing in line behind 50, 60, or 75 other men, waiting to be called to the front, he makes what today we’d call: “a baller move.”

He puts on his work hat and tool belt and grabs a spool of wire.

HE WALKS RIGHT UP TO THE FRONT OF THE LINE.

Skipping past all the other men, who watch and gasp at his presumption, he goes right up to the man at the table with the all-important paperwork and timesheets—the man who decides who gets to work that day, and he says:

“I’m here, boss. I’ve got all my equipment and I’m ready to go. Where do you want me?”

Astonished at such a bold move, the manager is looking at a workman, full of gumption, fully dressed, has all his gear, and is ready to go to work right now.

So he plays ball.

Foreman: “What’s your name, young man?”

Peter: “McElwee, sir.”

Foreman: “This way, McElwee. Follow that man. He’ll be your manager for the day.”

He gets the job.

And I’m telling you right now, in 2024, just thinking about that level of masculine audacity curls my already curly Irish beard even more.

Where did this come from?

No offense to my Stauffer ancestors; I don’t think it came from them.

Stauffers aren’t entrepreneurs. Stauffers don’t start businesses. Stauffers don’t drop out of school and move to Philadelphia at age 13 and teach themselves a skill that makes a full-time income. Stauffers don’t skip the line, moving past throngs of angry older men who feel they deserve a job more than you. Stauffers don’t do any of that.

Germans don’t do that. Well, at least not the Germans in my family.

Only the Irish do.

Only the Irish could “have enough neck” to be that bold, to make do with such awful circumstances, to dare that greatly, and to ask that much out of life.

Only the Irish could “eat Skip for dinner” and still grow up into successful businessmen.

Only the Irish could be abandoned by an absent father and survive on the run.

Only the Irish are so fiercely independent that they could wake up as a homeless teenager, drop out of school, and still find a way to fashion a career out of nothing at all without help.

When I heard about how Pop-Pop Pete would dress up in a nice suit and his prized, polished “Florsheim” shoes and stand, hat in hand, on the street corners of Philadelphia, singing radio hits from the likes of Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra to pretty girls walking by, I almost couldn’t believe how poetic it was.

That’s not to gloss over his failures as a husband and father, for that will always be part of his legacy, flattering or not.

But I’m telling you, standing here today, thinking back on my Pop-Pop, who was born 116 years ago, all I have is respect for a man who was dealt a very bad hand in life and did the best he could with what he had at the time.

It makes me thankful for the hard men like him who came from hard times and passed down a tradition of hardscrabble existence and survival to future generations.

It makes me thankful that I’ve never had to have “Skip” for dinner.

It makes me thankful that I’m Irish.

So, thank you, St. Patrick, for the holiday we still celebrate today, remembering what it means to be Irish. And thank you, Pop-Pop Pete: you never had any luck but proved that we don’t need it if we work hard.

Today, I’m self-employed, and so are many other people in my family: an uncle, one of my brothers, one of my sisters, and at least two of my sons and one of my daughters want to be self-employed.

And while we’re hoping for a little help along the way, we all know that the “Luck of the Irish” isn’t luck at all — it’s just the result of hard work.