In the late 1980s and early 1990s, like many Christian families in California, my family became fairly politically active.

People in our small social circle of conservative homeschool families often lamented just how “awful” California was becoming. Our politicians weren’t representing us well and were turning our state into a cesspool of oppressive government, high taxes, punitive regulation, and ever-increasing crime.

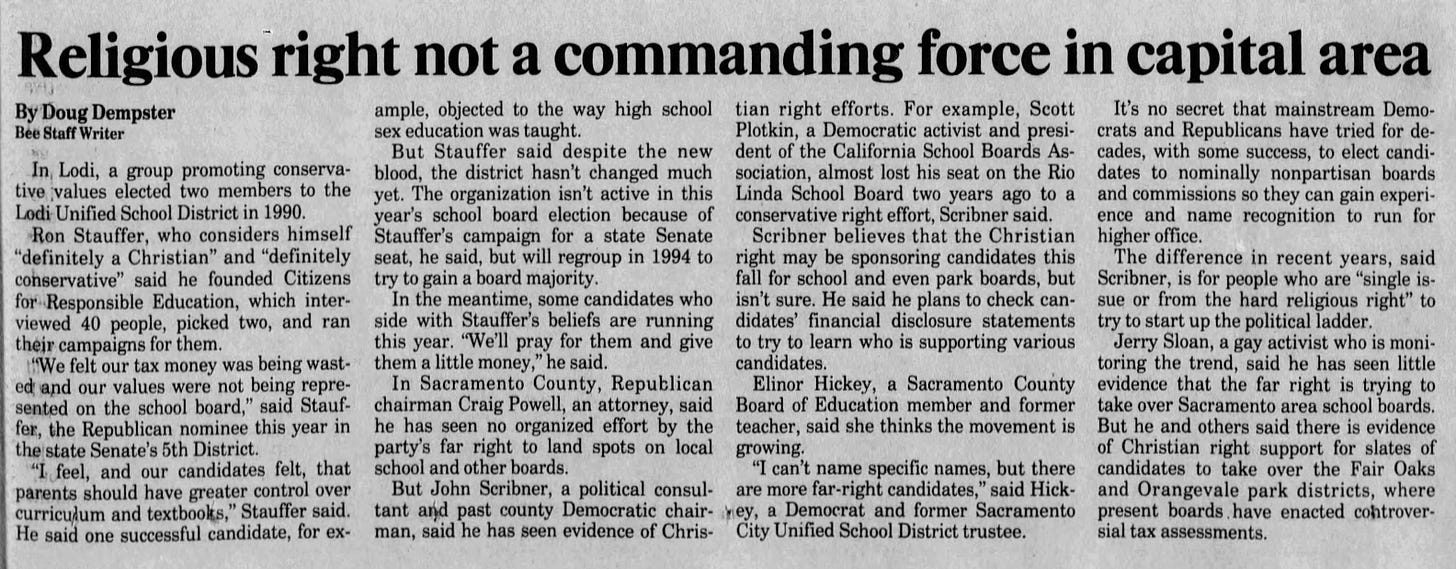

So, my dad, who had never held elected office before, decided to get involved in politics for the first time. He started small: in 1990, he founded a group called Citizens for Responsible Education, which vetted a few candidates to run for the local school board, backed them financially, and helped manage their campaigns.

I was just five years old at the time, but I still have vivid memories of that whole season of life that started back then. In addition to learning all about local elections with school boards (which was kind of ironic, if you think about it—we were homeschoolers, after all), my dad also supported a few races in the California State Assembly, U.S. Congress, and U.S. Senate.

I learned a lot about the political process as I sometimes spent evenings and weekends helping my dad volunteer for various campaigns. We screen-printed signs, posted those signs on the side of the road, stuffed envelopes and mailers, and walked door-to-door, handing out flyers for candidates.

As far as I recall, I was never really asked if I wanted to be a part of all this; I think it was just assumed that I would help. It was a family affair. I don’t know that I would have said “no” if I’d been asked, but I didn’t understand what it all meant and why we were doing it in the first place.

So many of the things people discussed and the words they used were totally foreign to me. What was a “cannadate,” anyway? Why did people who were in charge of schools call themselves a “school board?” And weren’t “principals” in charge of schools?

My very literal brain pictured a big sheet of plywood—a board—that said “school” on it; when I found out that school board members weren’t even teachers themselves, that made even less sense to me.

There were so many words thrown out by people who thought apparently it was all so completely normal, but I was often confounded upon hearing terms like: elections, budgets, deficits, primaries, taxation, districts, surveys, polls, precincts, voter registration, and even legislation.

What did it all mean? What were educational vouchers, the Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the Three Strikes Law? Why were we talking about baseball in politics? And why were people so passionate about things like this, to the point where they’d argue and even get angry about them?

The only thing that was clear to me was that some people were “for” certain things, while others were “against” them. I didn’t always have time to figure out what that meant, but I asked my dad to explain this whenever I could.

“Dad, what are ‘Mello Roos?’ Are they good or bad?” I’d ask.

If my dad supported an issue, it made sense that I’d support it, too—it would surely be the “right” position. After all, my dad was a “good guy.” He was a Republican. That meant Republicans were good, so I was probably a Republican, too.

The inverse seemed just as logical. If the other guys were against an issue we supported, they were taking the “wrong” position. If they were against my dad, they were “bad guys.” Those people were usually Democrats, so that meant Democrats were bad guys.

But I found out my dad didn’t exactly see it that way. He would correct me and say: “They’re not ‘bad guys.’ They’re our ‘opponents.’” This made little sense to me, and I wondered why we’d be opposing other politicians if they weren’t bad guys. Despite all the baseball metaphors, this wasn’t just a game after all; this was a moral battle of right and wrong.

Isn’t politics all about good guys fighting bad guys? I had assumed so, and I still thought so, even though my dad said it didn’t quite work that way.

Of all the things we did to help support our candidates, going door-knocking was, by far, my least favorite activity. Usually, I’d go out with one or two adults, and we’d hit the road with giant stacks of flyers and door hangars.

Walking for blocks at a time, we had big lists of registered voters that someone else on our team had previously highlighted, with each address color-colored. We knew who was and wasn’t registered to vote, which houses had Democrats, which had Republicans, and which had unaffiliated voters.

Based on our list, we’d hand out different types of literature. If we knew the residents of one address were Republicans, we’d give them a large, glossy door hanger with one particular message on it that had nice, full-color photography. These cost us a lot of money to produce, so we had to give them out very carefully.

If we knew they weren’t Republicans, we’d leave behind a smaller door hanger with a different, shorter message. These were printed on much uglier “highlighter green” paper with black smudgy ink that was much cheaper to print.

I didn’t mind simply placing a door hanger on the knob and walking away, but we weren’t allowed to do that: we had to actually knock on the door. Every time I knocked on a door, I winced, hoping nobody was home.

We had a rule that went something like: “If you knock three separate times, and nobody answers, you can just leave a hangar on the door.” I always wished nobody was home so I could just knock, place my flyer on the door, and run away.

(Sometimes, I admit, I would cheat, inflating my numbers by pretending to have knocked three times when I’d only knocked once or twice. I’m sorry, Dad.)

More often than not, though, someone was actually home. I always hated it when people came to the door. Usually, they were nice, and they’d open the door but leave their screen door closed and ask us what we wanted in a very defensive manner.

I would tell them I was passing out flyers for Richard Pombo or Dan Lungren (US Congress), Larry Bowler (California Assembly), Tom McClintock (US Senate), or Mel Panizza (Stockton City Council).

Depending on their political views, they might then open the screen door and step outside to talk to us. They’d tell us about who they voted for in the past or what their concerns were about the current election.

On occasion, people were nasty. They’d open their door just a crack and angrily shout: “What do you want? Are you selling something? Go away!” and slam the door.

One thing I learned very quickly going door to door was how I could immediately find out which houses had dogs. If a family had a dog in the house, the dog would start barking either when it detected me walking toward the house or the second I knocked on the door or rang the doorbell.

Side note: if I hadn’t already hated dogs by this point, this experience certainly cemented my disdain for them. Walking up to a stranger’s house to talk to people I didn’t know, who didn’t want to talk to me, about topics I didn’t fully understand was already hard enough… but it was made worse by vicious-sounding dogs that I thought wanted to bite me or kill me.

The ONLY thing that made going door-to-door worthwhile was how, after a long stretch of walking and knocking, there was a prize at the end: we would get a soda at the local gas station. Give me a 32 ounce icy root beer, and I was as good as new.

At the end of the election cycle, some of our candidates won their elections, and some didn’t. In my mind, this was hard to comprehend: we had worked equally hard for all of them, and they all seemed to support the same issues, so there didn’t seem to be any rhyme or reason as to why one person would win, while another would lose.

This was my first introduction to just how fickle voters are during elections and how, in truth, there is zero “science” in “political science.” Elections are ultimately decided by all kinds of things, I have found, but logic and common sense are not among them.

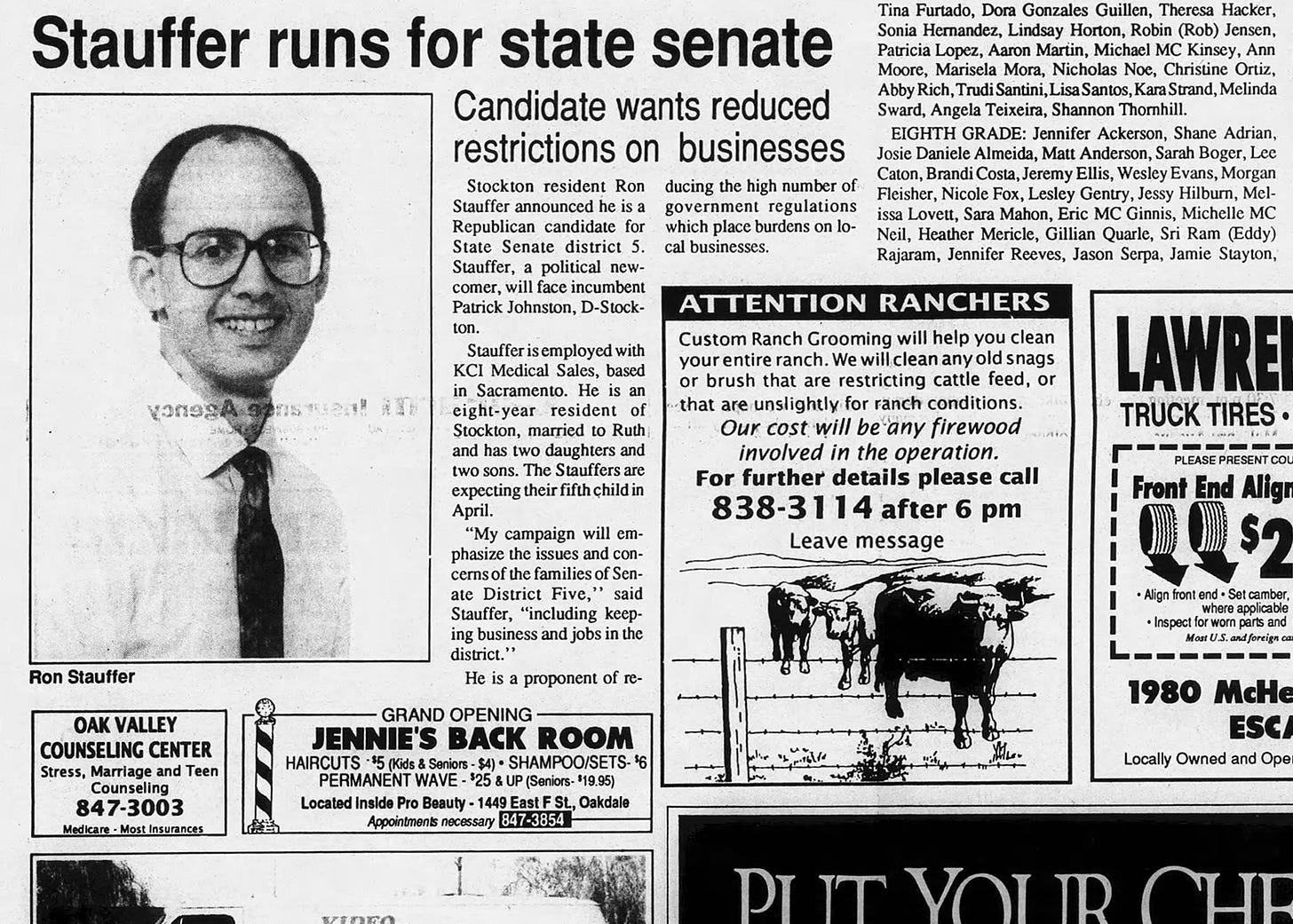

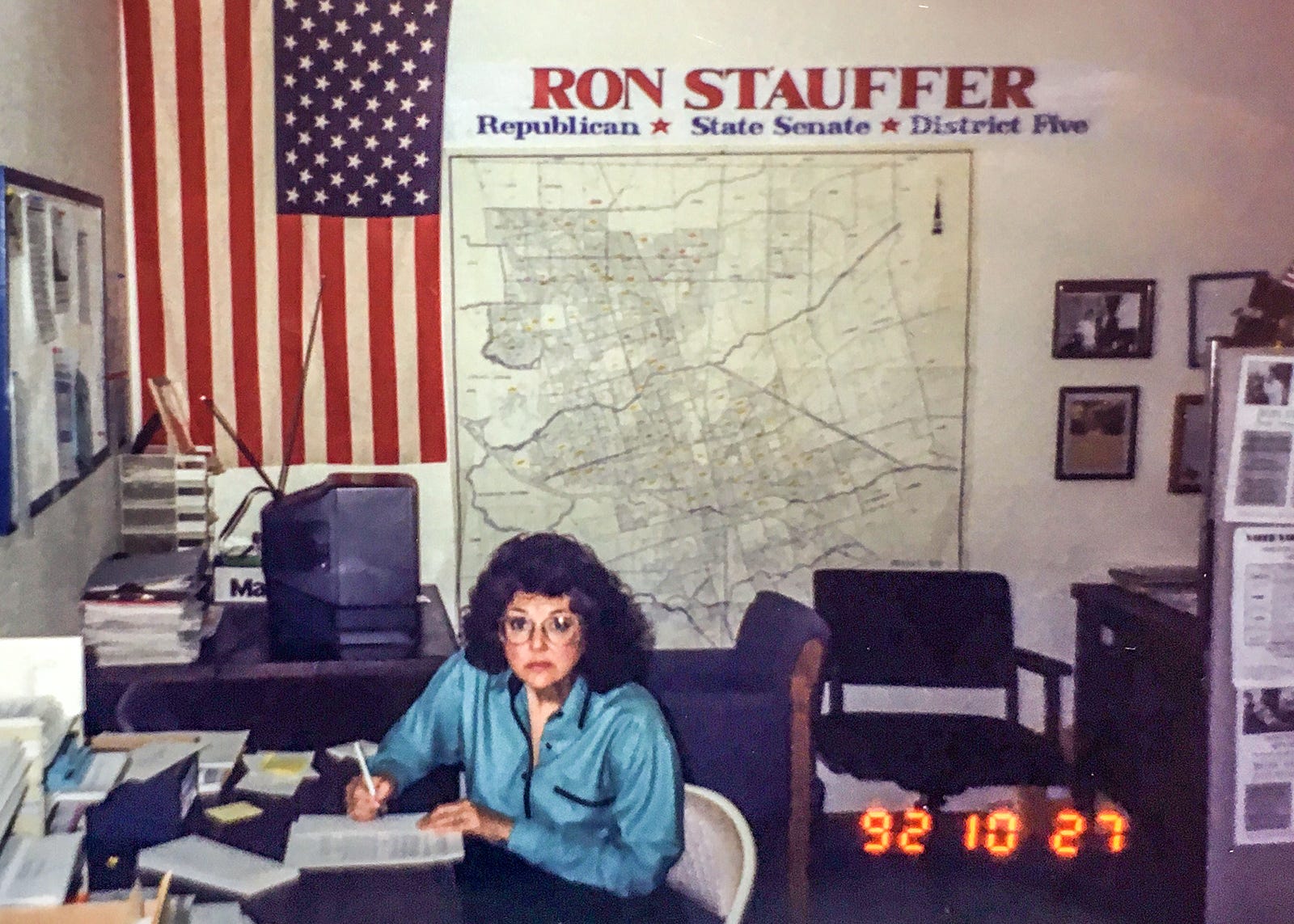

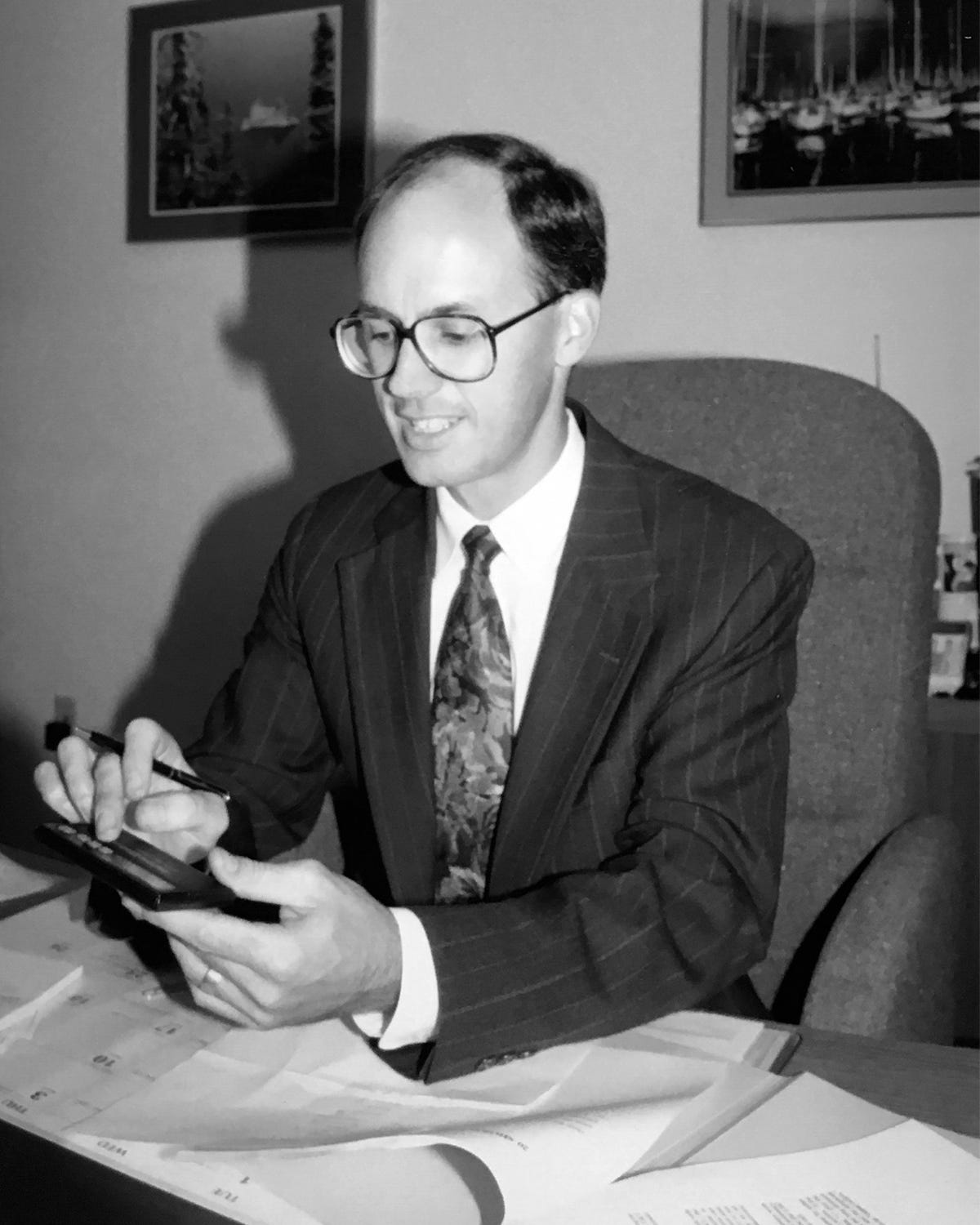

After two years of my dad’s initial involvement in politics, he decided to jump in with both feet by running for the California State Senate.

This was a shock because, aside from his recent efforts backing other candidates, he had no personal political experience to speak of. The only time he had been elected to anything in the past was being elected as an elder at church.

(Once again, I heard the term “elder board” and pictured a bunch of old men sitting around a table made out of a giant board of wood… or something like that).

So, when he made the announcement that he would be running for office himself, that really surprised me. Looking back now, if I were an adult who wasn’t related to him, I would have advised him not to run at all. I’d have told him he would make a bad politician for one simple reason: he’s far too honest.

My dad is bold and direct; he’s willing to say things people don’t like to hear. In real life, that tendency helps make a man a good husband, father, and friend. But as a politician seeking elected office, it can often be career suicide. As I learned from an early age, despite all claims to the contrary, voters actually like politicians who lie to them.

Oh sure, they’ll say they don’t like lying politicians—they will rant, rave, and scream angrily about how much they don’t like those g*ddamned, no-good, lying scumbag politicians… but you want to know the honest truth? Most people actually require politicians to lie to them in order to earn their votes.

If you ask a candidate for the California State Senate, “Will you reduce crime in our city?” a politician giving you an honest answer would tell you the truth like this:

“Actually, no, I can’t lower crime in our city. I can’t promise you anything like that at all. In fact, there’s very little I can do to affect crime in Stockton while serving in the State Senate.”

Who would vote for someone like that? Answer: very few people. People will instead vote for the candidate who makes up complete, utter fairy tales:

“Absolutely, I will reduce crime by half! If you elect me, I will fight for you in Sacramento. I will lower the crime in your very neighborhood. If you want cleaner streets and safer schools, give me your vote. A vote for me is a vote for a safer Stockton!”

This answer is a giant pile of steaming crap. It’s all lies. But it’s what people want to hear.

It was very strange to see how this played out in real life. As a stickler for truth myself, I have a hard time accepting it, still to this day. This is also why it was confusing to me to hear that my dad decided to run for State Senate.

Why would he want to personally get involved in low-down, no-good, dirty politics like that? Was he going to become a lying scumbag too, who over-promised and under-delivered for our friends, family, and neighbors?

I asked him about his decision and why he was choosing to run when he’d simply supported other candidates in the past. Running for office himself now, this was going to be far more disruptive to our lives. His explanation impressed me, even back then, as a young child.

“Well, Ron, everybody keeps complaining about how bad things are and how they’re getting worse. And they all keep saying, ‘Somebody ought to do something about it.’ But nobody’s willing to actually do anything. Nobody is willing to ‘be that somebody,’ so I will.”

That notion has stuck with me ever since: my dad wasn’t just spouting rhetorical feel-good nonsense; he was literally taking action to make a change in what seemed like a hopeless situation. As it turned out, he had tried to recruit multiple people to run for State Senate, just like he had in the past with the school board.

But nobody was willing to!

He dared a few people: “Oh, you’re fed up, are you? Really? So run for office!” and they’d withdraw like a shrinking violet, deciding they didn't actually care that much.

It was due to the reluctance of everybody else that my dad was going to become a politician himself. He decided to “be that somebody” everyone else was hoping would come along but who they weren’t willing to be themselves. This was a bold move.

By now, he had helped support candidates for the school board in Stockton, the school board in Lodi, the Stockton City Council, the U.S. Senate, the U.S. House of Representatives, and the California State Assembly, but nobody was willing to step up to fight for us in the State Senate. So he would.

Patrick “Pat” Johnston, a Democrat, would be my dad’s opponent or, as I secretly thought, the “bad guy” we’d be fighting against.

Pat Johnston was a career politician who represented everything that was wrong with California. He despised the Second Amendment, the death penalty, homeschooling, religious freedom, and the free market, and he loved big government, heavy-handed regulation, abortion, taxes, environmentalism, and labor unions.

He had helped push so hard for environmental regulations and useless red tape in the Central Valley that businesses were now leaving California in droves. That hurt our industry, took away our employers, eliminated our jobs, and shrank our tax base.

Many companies were relocating to greener pastures in other states that welcomed these businesses with open arms. In fact, the biggest part of my dad’s platform in the 1992 election was reversing the damage from business regulation that was now causing companies to flee California en masse.

My dad traveled all over San Joaquin County, asking farmers, manufacturers, and other business owners what their number one complaint was about living and working in the Central Valley. The answer, he said, was almost unanimous: too many rules, too much regulation, too much red tape and bureaucracy, and too many taxes.

This poor environment was making it impossible to run a profitable business, so they were all looking at downsizing, going bankrupt, or relocating to other states.

So after my dad’s announcement to run against Pat Johnston the “bad guy,” what followed was a season in my life that was a totally wild ride. A whole year of crazy, exciting, exhilarating, disappointing, angering, political involvement.

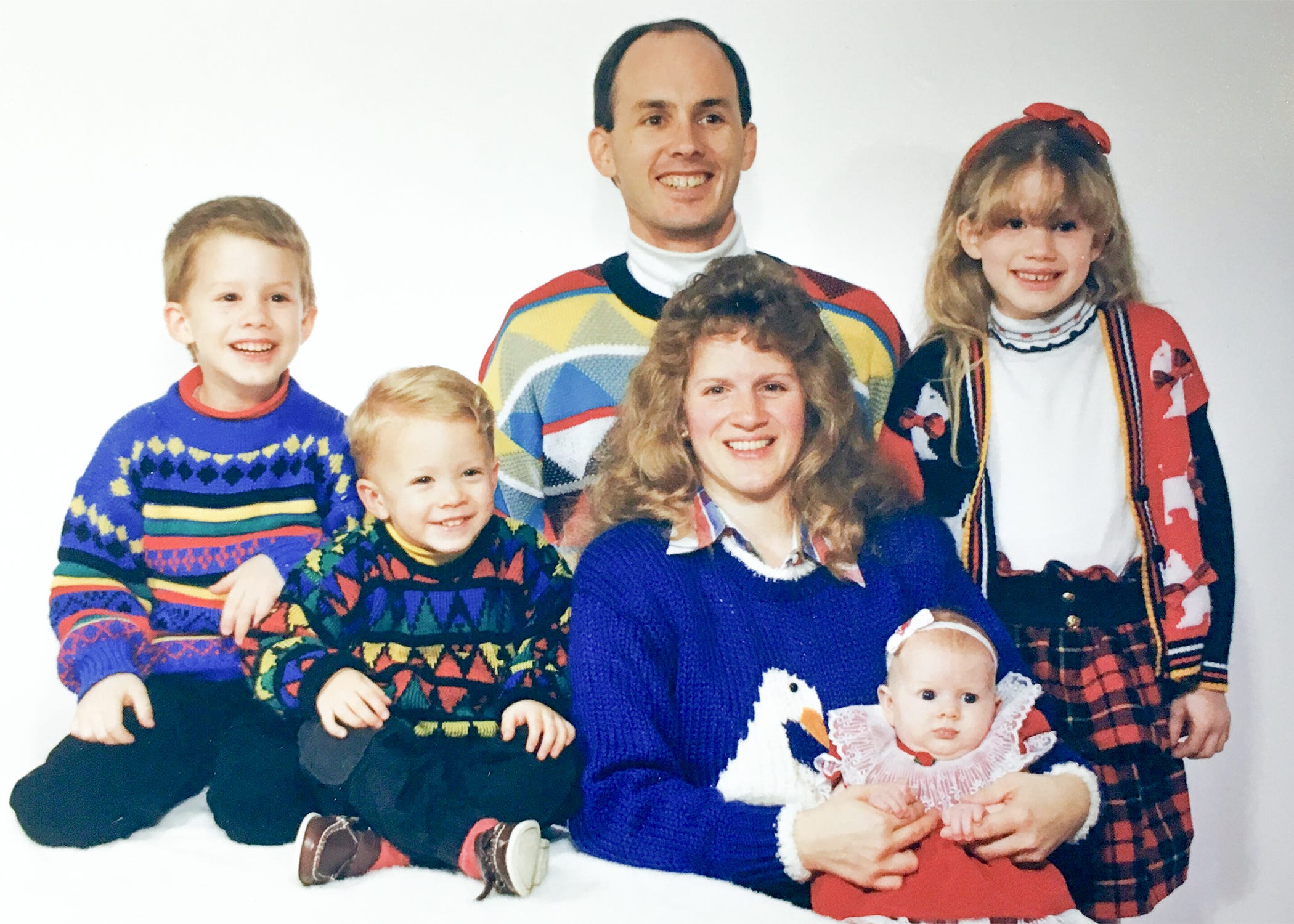

This time around, we kids weren’t just observers who occasionally volunteered for trivial tasks like envelope stuffing. On my dad’s campaign, our whole family got involved in a movement of political activity.

Aside from knocking on doors and placing signs on the side of the road at random intersections, we also met many of the local movers and shakers in the California Republican party and nationally known figures.

At various stages, my parents met with Alex Spanos (the billionaire and owner of the San Diego Chargers), Lt. Col. Oliver North, and even Vice President Dan Quayle.

This was a bizarre education for me as a young child: to meet people as a political volunteer and also for simply being Ron Stauffer, the son of Ron Stauffer, the political candidate.

It was SO strange seeing MY OWN NAME plastered on roadside signs, flyers, business cards, and even hearing my name spoken on TV and radio ads! People were talking about me! RON STAUFFER! What a trip!

Meeting the people involved was even weirder. Women thought I was cute and would pinch my cheeks and tell me so. Men thought I was smart and handsome and would shake my hand and tell me how wonderful my father was. All of it was so confusing and hard to comprehend.

Who were these people? How were they all connected? …and why did they care about my dad? How did they even know him? Women fawned over him in a way that seemed really awkward: beautiful ladies I’d never met before telling me how wonderful my dad was—that was very, very strange.

So was seeing people from other families: friends and strangers, husbands and wives together, making phone calls and driving around town doing errands for my dad… was this real life? My dad, my boring ol’ dad who sold hospital beds was actually kind of… famous? What?

The structure of government made even less sense to me. What even was the State Senate, or the California Assembly, or the U.S. House, or the City Council, or the School Board for that matter… and who cared? What did it all mean?

I asked my dad once, “Dad, if you win, when will we have to move to Washington D.C., and will it just be for a while, or forever?” My dad laughed at me and told me: “Don’t worry. We won’t have to move to D.C.”

But that didn’t make any sense. I wasn’t stupid. I knew Senators worked and lived in D.C. Why was he telling me this wasn’t the case? Why did adults always do this to me?

During the election, my dad’s mother, “Grammy,” drove up from Bakersfield to stay with us for a few days. While she was in town, we all went to a huge political event at a place called “Winners Gaming & Sports Emporium.”

Our whole family was there: mom and dad, the boys in our suits and ties, and the girls with their fluffy bangs and lacey dresses, everybody dolled up as fancy as we could be. There were balloons and confetti everywhere and music and food: a spirit of celebration was in the air.

I couldn’t understand any of what this was all about, and nobody would tell me. I knew it had something to do with my dad running for State Senate, obviously… but what?

I asked Grammy, “Is this a party to celebrate Daddy?” She seemed annoyed by my question and waved me off, saying, “No, honey, no, no, no.” But I wasn’t swayed.

I put two and two together: my dad was running for a political office, and this was a political rally. People were excited and happy… there was cake, confetti, music, balloons, and everything, and my dad was there. What else could it be?

“Yes!” I decided, “This IS a party to celebrate Daddy,” I shouted out loud for anybody to hear in defiance of what Grammy told me.

But it still didn’t make any sense: we were a conservative, Christian, Mennonite family. What on earth were we doing at a ginormous casino where people were gambling on horse races, drinking alcoholic cocktails, and smoking cigarettes?

The cognitive dissonance was stupefying.

Also, once again, why had we been supporting candidates for public school boards when we were homeschoolers? Our parents had always derisively referred to “public schools” as “government schools” and said they were “evil.”

So much about all of this made no sense to me.

Certain parts of the political campaign did make some sense to me. Politics, in general, as I’ve said, was very easy for me to understand because it was so binary:

The Democratic party was the problem; the Republican party was the solution.

Pat Johnston was a bad guy; my dad was a good guy.

At a basic level, this made sense. It was so simple: it was black and white. Dad was good, Pat was bad. End of story. But would the voters see it that way?

Even before my dad became involved in politics in a tangible way, we were always raised with an extremely partisan view of right and wrong. The political struggle between left and right was so clear.

For example, when my older sister’s cat gave birth to kittens, my dad said: “When kittens are born, they start out as Democrats. When they get older, they become Republicans.”

This, I found fascinating. “Wow, why is that?” I asked my dad.

“Well, because when they’re born, they’re blind. When they get older, they open their eyes.”

“Oh,” I thought. “It’s a joke.” But my very literal brain needed time to process this.

Still, the pure simplicity of good vs. evil, right vs. wrong, and Republican vs. Democrat made a lot of sense to my autistic mind.

What did not make sense at all was how the political process played out. There were many things that happened that I did not like at all. Many of the tactics that people engaged in—even Republicans—made me feel uncomfortable.

Even as a seven-year-old, my “bullshit detector” was fully formed, and there were times I was asked to participate in posturing that I knew was fake, and that really bothered me.

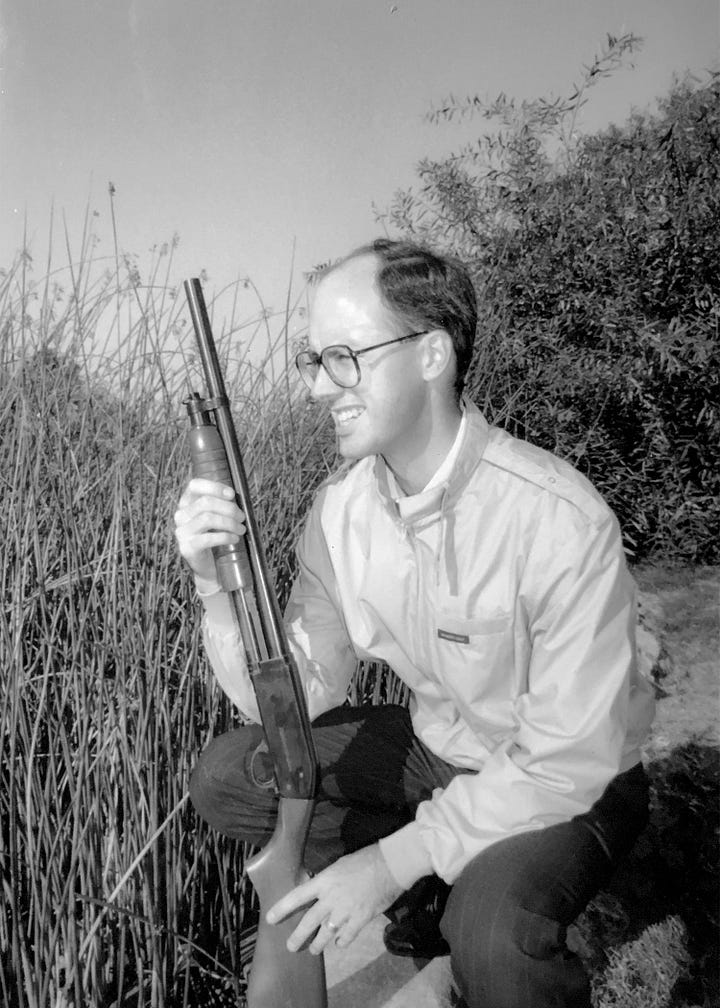

At one point, a photographer was hired to take pictures for the press of my dad holding a shotgun to show his support for gun rights. Due to the challenging sunlight at that time of day, though, the photographer got irritated after several ruined takes and insisted my dad take off his glasses.

So he did, and then, apparently, they liked the photos. Except that I (and everybody who knew him) knew that my dad was legally blind without his glasses. He couldn’t do anything without them—certainly not shoot a gun without them!

This really rubbed me the wrong way. I felt like it was deceitful and vain to publish pictures of my dad without his glasses on just because it “looked better” for the camera.

Also, as far as I knew, he didn’t even own a shotgun. If he did, I’d never seen it before, and one thing I was certain of was that he had never gone hunting before. So these pictures that made it look like he was hunting ducks in the swamp were totally fake.

Why was his campaign releasing obviously staged photos of him pretending to shoot a gun he didn’t use on a fake hunting trip he never went on while not wearing the glasses he would have needed to pull the trigger? That bugged me a lot.

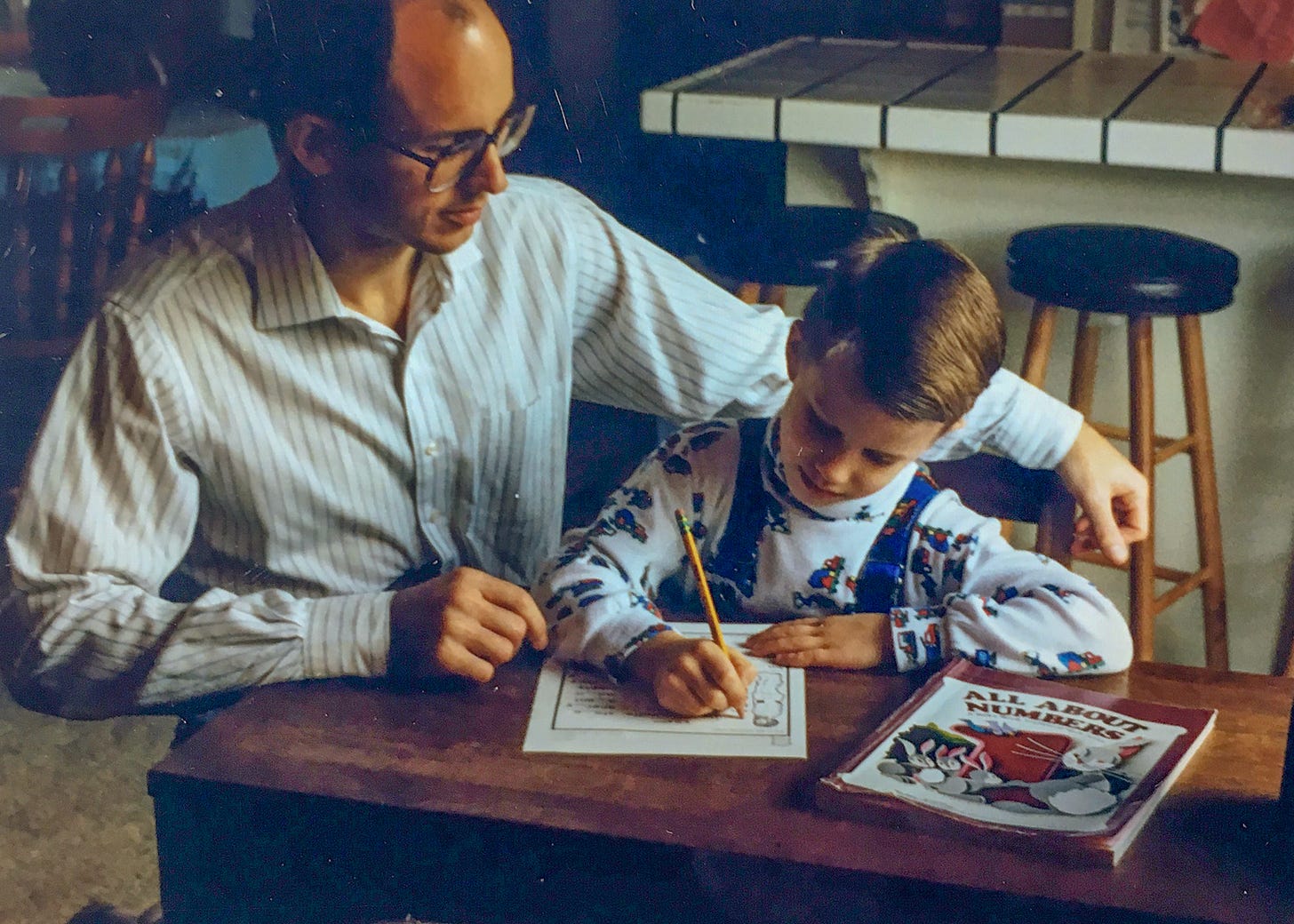

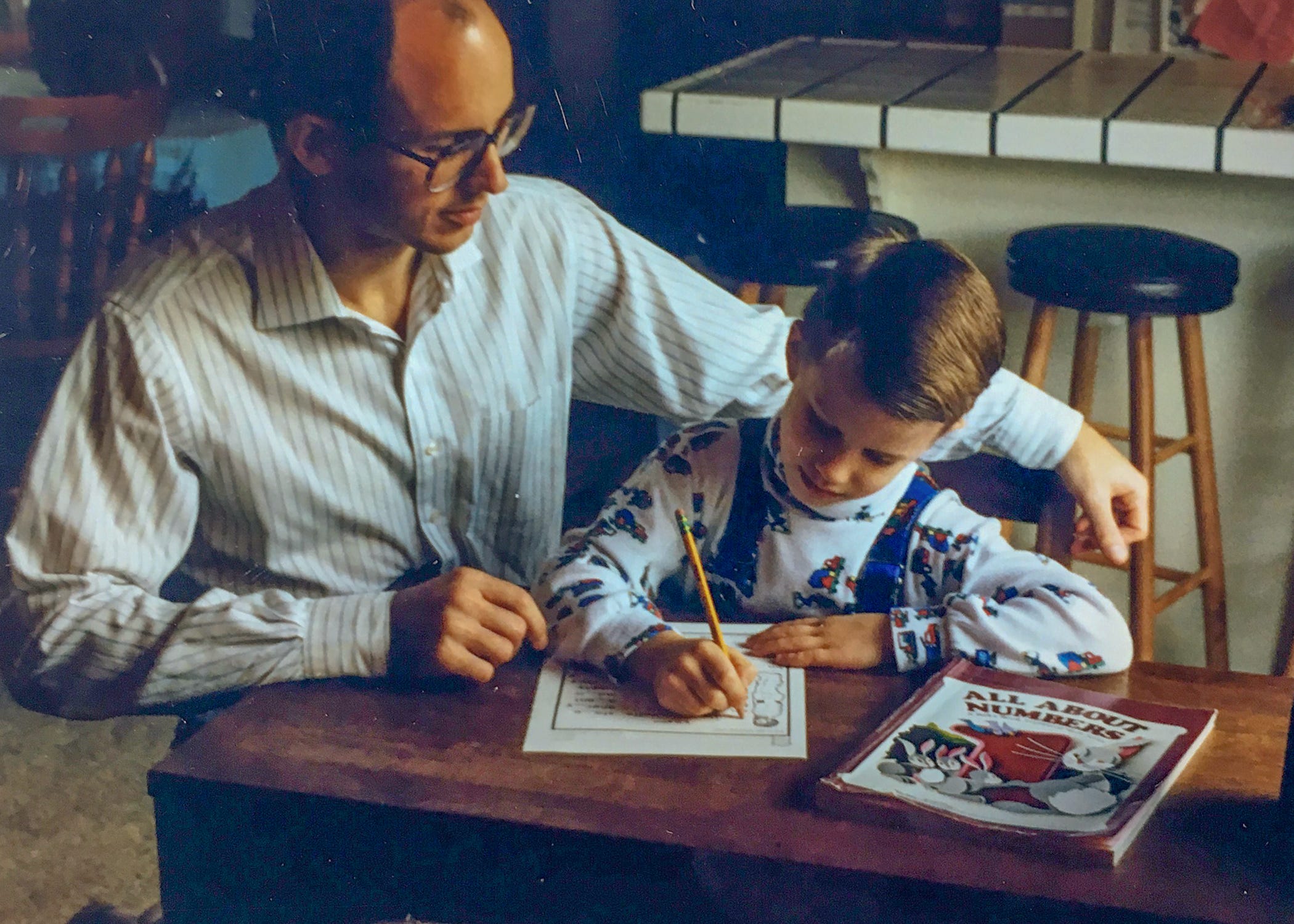

Worse, one day, a photographer came to our house to photograph “a day in the life of a conservative, Christian, homeschooling family.” I didn’t like the way this guy was intruding into what was normally our very boring, very private daily ritual, and I did not want to be on camera.

But nobody ever asked me. I was just told that this was what we were doing. During the shoot, the man suggested we get a photo of my dad “homeschooling” one of his kids.

As his oldest son, I was told to awkwardly pose for the camera seated at my desk. I did so grudgingly and placed my hands where the photographer told me to in a completely staged pose. In the picture, my dad looks over my shoulder as I pretend to fill out a spelling worksheet for the camera.

Everything about this picture was fake, and I hated it.

First of all, we were ridiculously overdressed. My hair had been brushed especially nicely, and I was wearing a turtleneck shirt and overalls. I hated fancy clothes like this, and I was way overdressed for the occasion. I was sure people would see through this obvious costuming.

Second of all, my dad never helped me with my English homework. He helped me with math sometimes, but not English. So pretending like he taught me this subject, to me, seemed like a lie.

Third of all, they made me pretend to fill out a grammar and spelling worksheet that I had already completed. You can’t see it in the photo, but all the blanks are already filled in. This felt deceptive to me as well.

Fourth of all, the worst part: I was given a broken pencil to hold for the photo. This actually outraged me.

In the end, in the picture, I can be seen sitting at my desk, overdressed in a turtleneck shirt with Richard Scarry’s Busytown cartoon characters on it, posing with a pretend smile, acting like it was normal for my dad to loom over me with his arm around my shoulder while I’m using a broken pencil to fill out a “G is for Giant” vocabulary worksheet that was already filled out.

Basically, I was forced to produce political propaganda. I didn’t like any of this.

I felt used, like I was being complicit in a lie. I told my dad and the photographer that I didn’t want to pose for this perfectly staged photo that was supposed to look like a surreptitious picture of a perfect homeschooling family in action, where a photographer just happened to be there.

I especially couldn’t get over the fact that the stupid pencil I was holding was broken—it literally had no lead in it. I was told to just pretend to be writing words on the page so the cameraman could get his photo.

This made me angry: I held up the pencil and showed it to the photographer: “This is broken… see? It doesn’t have any lead in it!” I have never forgotten his response.

“It doesn’t matter; the camera won’t pick that up. Nobody’s going to know.”

Of all the things I’d endured in this political campaign, pretending to be a perfect member of a perfect homeschool family, smiling, shaking hands, and going door to door, this hurt me the most.

We were lying to the public. I was lying to the public.

I didn’t even want to be photographed in the first place.

I hated the photographer’s response. I hated his attitude. I hated politics.

Nobody ever asked me! I never wanted strangers with cameras coming into our house, spending time, thought, and effort to pose us in the most photogenic way possible in order to pretend we were some perfect conservative, Christian, homeschooled family, as though that were the reason why people should elect my dad to the State Senate.

Also, this pressure put on us kids was enormous. I felt like, “If I screw this up and don’t participate with a good attitude, my dad might lose the election, and it will all be my fault.”

But I wasn’t a part of this political campaign. I wasn’t running for office!

I felt like a pawn in a game I didn’t consent to, but I also felt like I had no voice. I was just a cog in a wheel in a machine, and I had been told—not asked—to play a part in it.

I hated all the pomp and circumstance of these everyday events that seemed so important to the press, to the campaign, and to the voters.

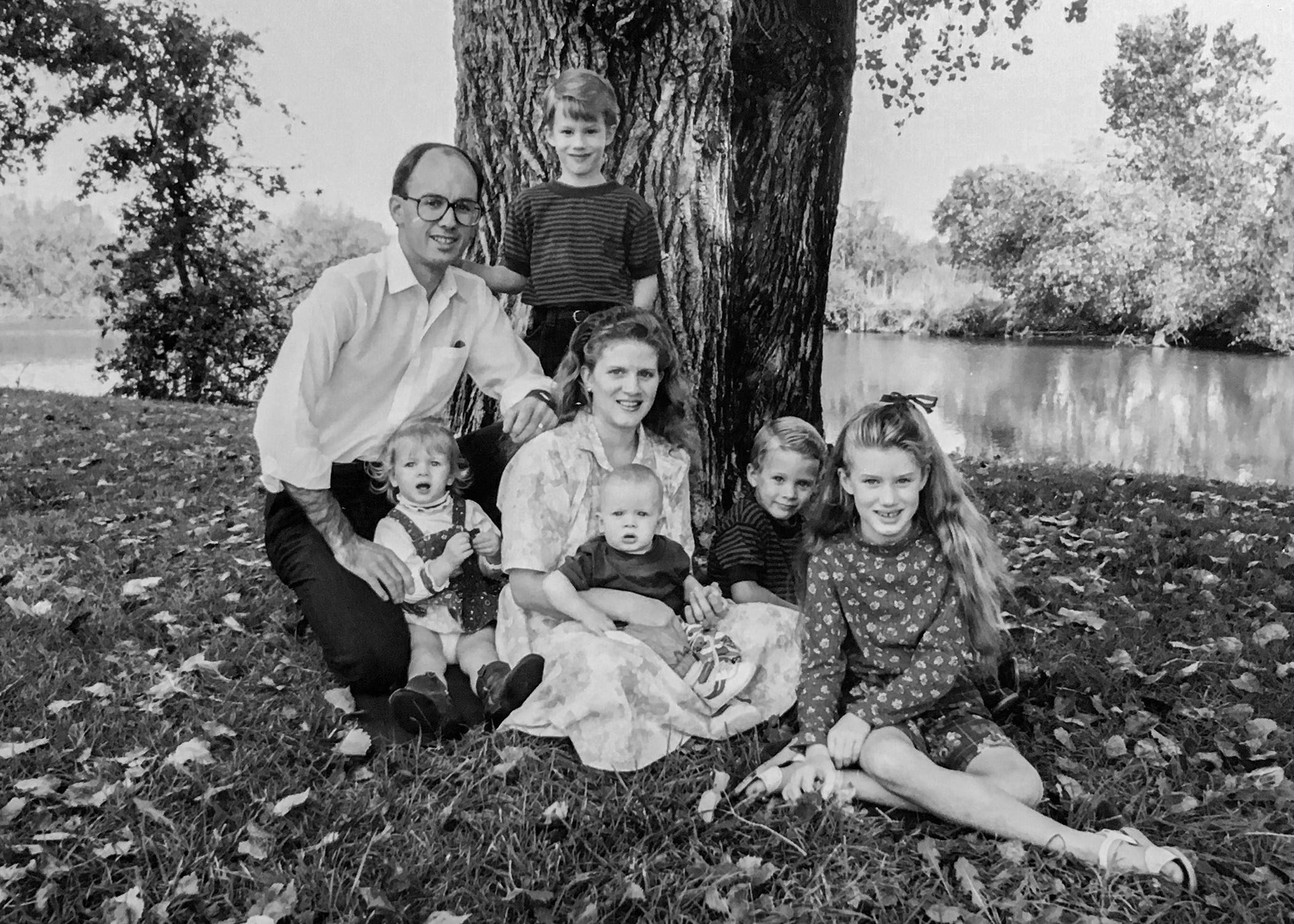

Why did we have to dress up all nice and get family photos at Lodi Lake in black and white? Why did the newspapers care what we looked like? Why did we have to smile for the camera in nice, clean clothes, with perfectly coiffed hair, and pretend everything was just peachy all the time?

Why did everybody look at us kids as ornaments or decorations and not as actual living, breathing human beings with our own thoughts, feelings, and opinions?

I despised the feeling of lying, no matter how small it was and no matter how little anybody else seemed to care about it.

When I saw that picture of myself on a campaign brochure, pretending to fill out that “G is for Giant” grammar worksheet with my stupid broken pencil, I was angry.

Literally, legitimately, angry. But what could I do? Nobody listened to a seven-year-old.

Although I hated being paraded around in front of a camera like I was a perfect son with a perfect father in a perfect family, there were some things my dad did on the campaign trail that proved to me (and a lot of other people) that he was a very brave man and a tough fighter.

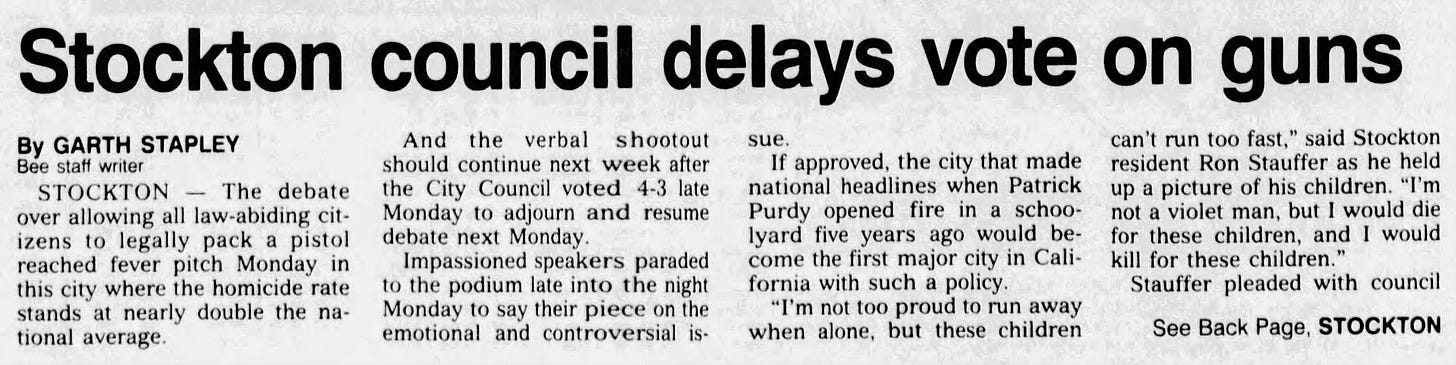

One notable incident involved a kerfuffle between my dad and the Chief of Police. In a bizarre situation, despite the fact that Stockton had been listed by the FBI as one of the “Murder Capitals of the USA,” our idiot police chief had somehow decided that giving concealed carry gun permits to lawfully abiding citizens was a bad idea and said that it wouldn’t reduce crime.

So, like many law-enforcement officers in California started doing in the 1990s, he just decided to stop issuing permits altogether. That was too much for my dad.

One night, I watched our local television station and saw my dad, the balding man with enormous glasses, the State Senate candidate, Ron Stauffer, hold up a picture of my family in front of the video camera that showed all of us kids and challenged Stockton’s Chief of Police by name for his cowardly stance on self-defense.

I wish I could find that video clip. I know it’s out there somewhere. Reconstructing this moment from memory and from newspaper clippings I found, he said:

“Are you telling me, Chief Chavez, that you don’t believe my children are worth protecting?

Are you telling me, Chief Chavez, that I should not be able to defend these children from a murderer?

Let me tell you, Chief Chavez: I am not a violent man, but I would die for these children.

…and I would kill for these children.”

DAAAAAAAAAAAMMMMN!!!

It was very weird seeing my face in a family photo held up to a television camera at city hall in a political scuffle between my own father and our Chief of Police.

What a crazy experience. I could not make sense of everything I was seeing with my eyes and hearing with my ears.

What I can say is that, over the years, I have met many people who grew up wondering if their fathers would have protected them or laid down their lives for them if their lives were threatened. …and I have never had to wonder about this with my own father.

How could I doubt his sincerity when I watched him—with my own two eyes, on live television—directly challenge our Chief of Police while holding a picture of me? I have never forgotten that.

Make no mistake: no matter how much I felt like a pawn in this political campaign, that day, my dad proved he had Cojones.

As election day finally came into view and summer turned into autumn, one of the final events I remember is how my mom sent my dad and me on the strangest errand of my childhood.

Over the years, my mom had made hundreds, maybe thousands of plates of delicious, homemade cookies baked carefully with love in every bite to give to friends and family we cared about.

But count me as surprised when my dad and I got in the car to give a plate of fresh-baked persimmon cookies to none other than our nemesis, the archrival himself—the bad guy!—Pat Johnston!

This blew my mind.

Pat Johnston was the enemy! He was a Democrat! He was the evil man my dad was running against to save California! Why on earth would we give him cookies? A bad guy like him didn’t deserve my mom’s delicious cooking! We wanted him to lose the election, not have a jolly holiday!

What was up with that?

Of course, as Christians we knew that Jesus tells us in the bible: “Love your enemies.” So we would be giving my mom’s highly-coveted cookies to Pat Johnston because he was our enemy.

Fine. I accepted this grudgingly but not gracefully.

I was confused and angry the whole time it took to drive to his house. I was even angier when we parked the car across the street, and looked a Pat’s massive, expensive, luxurious, house.

I was seething with rage and jealousy as we walked to Pat’s front door holding a plate of yummy, orange-colored, persimmon-flavored cookies. I knew these cookies would be delicious, and I knew all that deliciousness would be totally wasted on that stupid Johnston family—the Stauffer family’s mortal enemies.

I was galled by the fact that it was always the smallest families we knew who inhabited the largest, most comfortable homes while the largest families, like ours, shared tiny houses… and the Johnstons were no exception to this unfair fact of life.

We walked to the front door, and I pressed the doorbell. I jumped when I heard an actual DOORBELL, with real tube bells ringing throughout this giant, expensive house that was home to only two kids.

I wasn’t exactly sure what would happen next. Here we were, political enemies, bringing an offering—a peace offering?—of home-baked dessert.

I wondered if the Johnstons would think we were trying to poison them: I imagined the old trope of a medieval knight offering a poisoned glass of wine in a chalice to his enemy in a toast before they went off to fight each other in a jousting duel.

Wouldn’t they be able to see through such a ruse? I wondered. It’s too obvious.

Of course, I knew that we hadn’t poisoned the cookies—or, I was pretty sure, at least. But how would the Johnstons know?

Surely, they would suspect the cookies were poisoned, right? Why wouldn’t they? This would be the perfect way for my dad to win the election: the bad guy is cruising along toward victory until, alas, he dies suddenly, for no expected reason, and, miraculously, my dad wins!

Tah-dah! It was perfect! Except that wasn’t the plan at all, and I knew it.

After the doorbell rang… nothing dramatic happened. A surprisingly tall, aloof teenage boy with pierced ears (gasp!) opened the door and said: “Uhh, hello? Can I help you?”

He took a very confused look at me holding a plate of cookies with shrink-wrap on it, then looked up at my dad. My dad told him he was Ron Stauffer, and I was Ron Stauffer, and we were bringing over some cookies for a happy early Thanksgiving to the whole Johnston family.

He seemed absolutely baffled and slowly reached out to accept the plate of cookies, saying, “Oh, wow, thanks, I guess…” and then closed the door.

I knew the cookies weren’t poisoned, but I was certain their son would have suspected they were.

Why else would your political opponent come and bring you cookies in the middle of an election? I imagined that after he closed the door and we walked back to our car, he probably threw the whole plate in the trash can and never even told his parents that we had dropped by.

I didn’t really hate this young man. I didn’t know Pat Johnston’s son, whatever his name was. It’s just that he was the first-born son in the Johnston family, and I was the first-born son in the Stauffer family, and I was positive he was the exact opposite of me in every way.

He was tall, he probably went to public school, his family was obviously rich, he lived in a giant house, and he only had one sibling. I hated that he had pierced ears. And I really hated that now, we gave them cookies.

They never gave us anything. They probably never even thought of us!

They were just living their stupid lives in their huge, stupid house with their enormous stupid income, being stupidly popular, and going to a stupid public school like stupid, normal kids.

But even aside from the way we were raised, this young man, his father, and their house represented evil in my mind. Pat Johnston was as bad as any bad guy could be.

First of all, he was a Democrat.

Second of all, he was an incumbent politician who represented everything that was wrong with California. He was the guy who had made everything so bad in the first place.

Third of all, and most crucially, he was my dad’s opponent.

My parents often talked at home about how horrible Bill Clinton was. As far as we were concerned, Bill Clinton was basically Satain in our house. But Clinton lived far, far away from us. So he didn’t seem real to me.

Pat Johnston, though, was very real: he lived in our same town. I had seen him in the flesh; I watched him debate my dad on TV. I had just gone to his house and even given his son a plate of cookies for Pete’s sake (for Pat’s sake?)

In my mind, Pat Johnston was the worst man I could think of, like a comic book villain. He opposed everything we stood for: our family, our faith, our freedoms, and our lifestyle.

I felt like my dad was Superman, and Pat Johnston was his nemesis, Lex Luthor.

Sometimes, I would literally imagine him hiding out in his underground lair, smoking fat cigars, rubbing his hands together with glee, and plotting the evil takeover of our country. He was the worst bad guy I could possibly imagine.

And there was only one man who could stop him: my dad, Ron Stauffer.

Except, of course, in the end, he couldn’t.

My dad lost the election. I was completely crushed. It had all been for naught.

He lost 57% to 37%. My dad has gone on record saying he was “creamed” by his opponent; but the stubborn child in me refuses to admit that. I don’t believe that he—that we—wasted our efforts. I like to say that we “almost won.” Because, damn it, we almost did.

Election night was one of the most profoundly disappointing days of my life, still to this day. We stayed up late, watching the returns on TV, and when I saw the red and blue bar charts superimposed on the screen, I knew that we had lost.

It was just so sad. I looked at the results and was personally affected. It didn’t seem fair.

All that work: the door knocking, envelope stuffing, rally-going, meeting-and-greeting, cheek pinching, posting of roadside signs, posing for intrusive cameras—we did all of that, just to lose?

How?! We were the good guys! Couldn’t people see that?

When it was all said and done, as sad as it was, the next few days were, strangely, a total high for us: it was like we were floating on clouds.

We knew my dad lost the election, but there were so many people who were supportive and who openly told us that they’d voted for him.

Folks I never even imagined came out of the woodwork to tell us they were sad my dad lost because they’d voted for him. For goodness’ sake, our babysitter told me she voted for my dad! I hated that woman with a passion, but after election day, I was shocked and pleasantly surprised that she could at least do one thing right.

There was one thing I was glad about now that my dad had lost the election and wasn’t going to be a politician after all. Now that he wouldn’t be a Senator, we wouldn’t have to move to Washington, D.C.

So, election season ended, my dad lost, and everything went back to normal. Which I was actually okay with. Except for that one nagging thought that I simply could not shake: whatever became of Pat Johnston?

I don’t know. But in my mind, I imagine that the evil, power-hungry maniac, the bad guy of all bad guys, is still living today in the sewers, along with the Ninja Turtles and Power Rangers, guffawing with his wild madman laugh, still looking for ways to ruin California, take away our guns, overthrow the United States of America, force mandatory abortions on women, and lock up homeschoolers like us.

I could be wrong, but I don’t think I’m that far off. Maybe that was his fantasy, too.