Les Noces: The Russian Wedding Singers

I sang in Stravinsky’s dark, four-piano wedding ritual and I’m still not sure what it all means.

Scenes (if you want to skip ahead on the video):

00:00 (Part I, Scene I, The Bride's Chamber)

05:16 (Part I, Scene II, At the Bridegroom’s)

11:18 (Part I, Scene III, The Bride’s Departure)

14:22 (Part II, Scene IV, The Wedding Feast)

Of all the classical singing gigs I’ve participated in, one that stands out as the strangest, the hardest, and the most confusing was Les Noces (or Svadebka), Igor Stravinsky’s “proto-feminist” work about a forced marriage among Russian peasants.

When I was still actively singing, and was looking for opportunities to perform in meaningful musical works in any capacity, a group I wasn’t a member of put out some feelers looking for a tenor to sing in a summer music festival at Colorado College.

I got an email from the director of my choral group asking if I was interested in joining her friend’s festival performance. I read the email and pondered it for a bit.

Hmmm… Stravinsky? I wondered. That sounds… really hard.

I’d never performed anything by Stravinsky before… and singing in Russian? That would be quite a challenge.

At this point, I’d already been singing German Lieder, French Mélodie, Italian Arias, Latin Masses, English Oratorio, and even Spanish Zarzuela… but a Russian cantata?

That would really be a stretch.

I’d only sung once in Russian before: Rachmaninoff’s “Bogoroditse Devo” (one movement from his All-Night Vigil and the Russian equivalent of “Hail Mary.”)

However, I was pretty sure our diction wasn’t that great, and it was a very short piece—there were only about 20 words in all. Plus, it was quiet, pensive, and sweet. This was going to be way more complicated; the literal opposite in many ways.

Les Noces was something I hadn’t even heard of before. Of course, I’d heard all about the Rite of Spring before, and I already liked Pulcinella and Petrushka, but I had to look up this obscure work with a French name on Wikipedia to find out what it was.

The first thing I noticed was that it wasn’t an opera, a song cycle, or anything else I was familiar with. It was a ballet. That was weird.

But we wouldn’t be performing it with ballet dancers: it would just be instrumental with a chorus and soloists. That was weird.

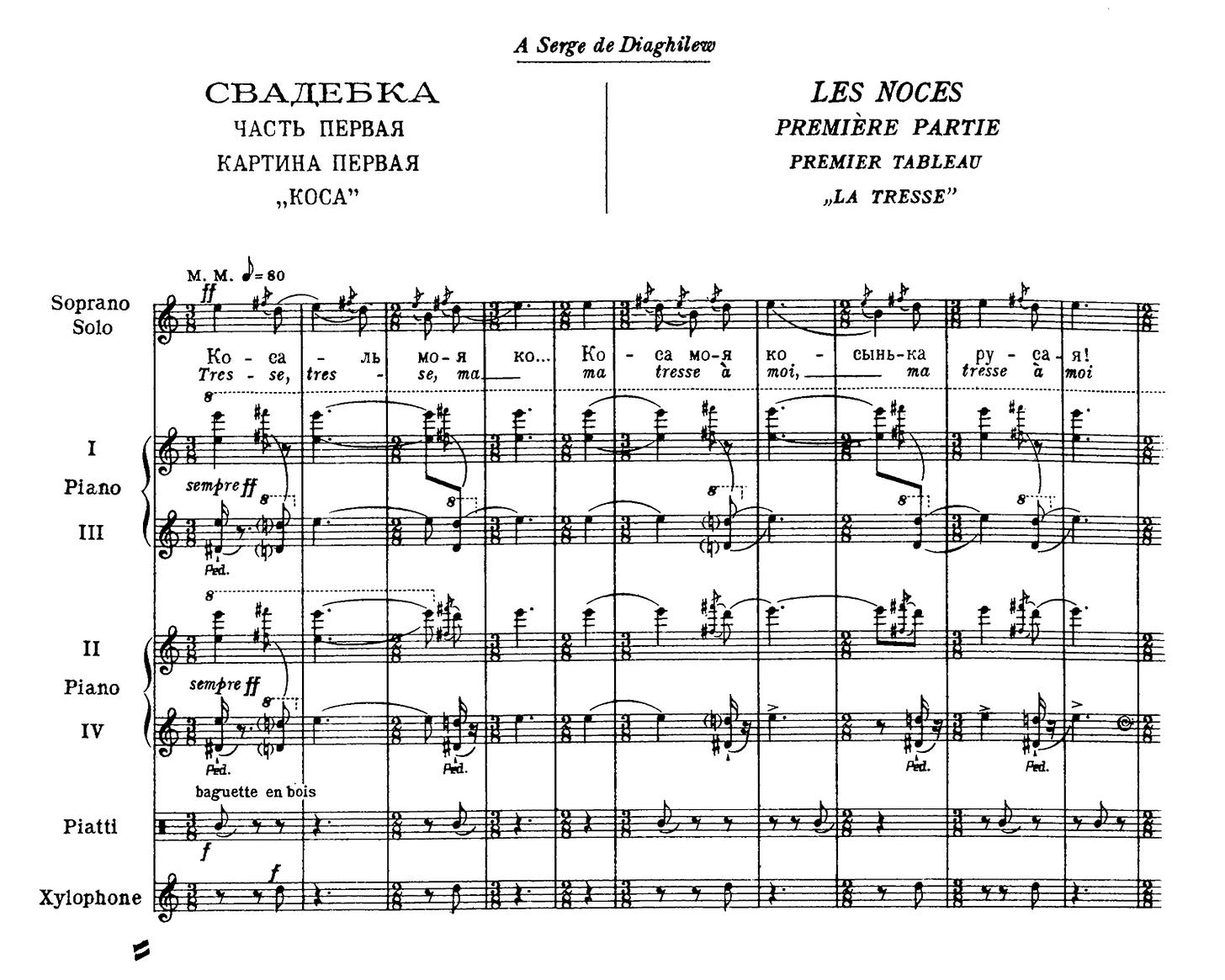

The second thing I noticed was that it didn’t have an orchestra. Or, it did, sort of, but the orchestra consisted of four pianos. That was weird.

I was intrigued. Actually, I was confused. Nothing about this musical work made any sense. On top of all the strangeness about it being a ballet without ballerinas, performed with four pianos at the same time, the more I looked into the work, the stranger it seemed.

This Russian music wasn’t even performed in the Russian language as it’s currently known. It was written in an archaic form of Slavic liturgical language categorized as “Church Slavonic” that nobody speaks regularly today.

So we’d be singing Russian words that Russians don’t understand? That was weird.

But seriously, the deeper I dug, the weirder it got. It was the story of a peasant wedding—an arranged marriage—told from the perspectives of everyone involved: the bride, the groom, the parents, and a group of villagers echoing like a Greek chorus in the background.

At one point, the groom yelps out in a super-high, feminine, falsetto range, like a high-pitched frog, croaking and shrieking awkwardly while the rest of the wedding party talk busily amongst themselves in a cacophony of disagreement.

What? That was weird.

Continuing further down the path of weirdness, I noticed that the piece doesn’t even have a consistent name:

It’s called “The Wedding” in English, but it’s never sung in English.

It’s called “Les Noces” in French, though it’s rarely sung in French.

It’s called “Svadebka” or “Свадебка” in Russian, though, again, it’s not really sung in today’s Russian either.

I reviewed all of this, and was overwhelmed by it all—where it came from, why it exists, what it meant in the past, what it means today. After about 15 minutes, I was so totally, utterly confused by the whole thing that I decided what to do.

“Yes, I’m in,” I emailed back.

I just had to be a part of this musical experiment I’d never heard of before that made absolutely no sense, by a composer I didn’t understand, in a language I knew nothing about, created with a purpose, in a time and for a context I wasn’t familiar with.

How could I say no?

I thought of the quote from my favorite book, “The Little Prince,” which, translated into English, says:

“When a mystery is too overpowering, one dare not disobey.”

This mystery was indeed overpowering, and I dared not disobey.

To recap: I’d be singing a Russian work that wasn’t really in Russian, for a ballet that wouldn’t have any ballerinas in it, at a college I wasn’t a student at, with a vocal group I wasn’t a member of, to celebrate a fictional wedding by people who didn’t want to get married in the first place.

WOWZA! Yes, yes, yes! (Or, da, da, da!)

I had no idea what to expect, but when I was walking to the college campus for our first rehearsal, I was pleasantly surprised to bump into Dr. John, a graduate from Juilliard, whom I’d sung operas and choral works with a few times in the past.

“Hey there, good to see you!” I said.

“Nice to see you as well,” he said, opening the door.

“So, why did you sign up for this one?” I asked him as I entered the building.

Still holding the door open for me, he paused as he looked down at the ground. His face became serious.

“You know, I’ve studied Stravinsky for decades. I know almost everything he’s ever composed. Les Noces is the only one I can’t understand. It doesn’t make sense to me.”

“Wow, me too,” I said. “It’s totally blowing my mind.”

“Yeah. I’m hoping that by singing it, I’ll finally understand it,” he concluded.

The rehearsals were fascinating. We were given recordings to learn proper diction from a Russian expert named—you guessed it—Vladimir.

(I spent hours listening to these clips… thanks for all the help, Vlad!)

We talked about weddings, pianos, the antiquated Russian language, the bizarre timings, the explosive musical riot that is the final scene (the Quatrième Tableau), where the stacked, interlocking rhythms with multiple pianos playing asynchronously clash with the chorus in an insane mess of noise.

It was really hard to make sense of the musical score since it was written in French and Cyrillic characters, and we sometimes had to pencil in phonetic diction by hand.

We had a Russian language professor from the college come give us live lessons on diction, and let me tell you, we all made some extremely embarrassing and ridiculous sounds as we tried to understand how to pronounce things like the slow, exaggerated “L” in words like blagoslovyén.

(Think of Gru, the main character in Despicable Me, and you’re on the right track.)

We burst into laughter many times as this woman tried to explain how some Russian words have to be said like you’re being punched in the stomach, or like you’re bending over and using two hands to pluck an extremely heavy pumpkin off the ground.

KARTINA VTORAYA: U zhenikha

Prechistaya mat’, khodi, khodi k nam u khat’ svakhe pomogat’ kudri raschesat,

Khvetis’evï kudri, Pamfil’icha rusï, Khodi, khodi nam u khat’, kudri raschesat.

Chem chesat’, chem maslit da Khvetis’evï kudri?

Chem chesat’, chem maslit da Pamfili’cha rusï?(One word sounded just like “Kah-BEECH-you” but she told us about 17 times that we were saying “BEECH” the wrong way, and we had to close our mouths halfway and try to swallow our tongues while still singing.)

What a hoot.

The whole experience was crazy.

It was hard.

It was weird.

It was work.

No joke. This was a serious performance about a serious subject matter.

Les Noces is a stark depiction of a 19th-century Russian peasant wedding, where the bride and groom don’t know each other, and are swept into a communal ceremony for an arranged marriage they don’t control (and may not even want).

It isn’t a love story. It isn’t romantic. It isn’t even happy, necessarily.

It’s just a folk tale, likely an amalgam of many true historical experiences—a graphic depiction, using music and words—of a poor life of hardscrabble existence in a frozen land of limited choices where people are simply told what to do, and they do what they’re told.

I wanted to take all of that very seriously.

I’m glad I got to do it. I invited one of my sisters to come to the final performance, and she did. We had talked about it ahead of time, and I told her what it was based on.

She sat in the audience and took it all in. I don’t think she was prepared for what she saw and heard.

It was loud, brash, and jarring. It was confusing and weird. It was dissonant and unconventional.

When the concert was over, we left the music hall together. As we walked, she asked me a strange question I wasn’t expecting.

“So if this whole thing is all about a woman who doesn’t want to get married, what happens in the end?”

I paused, trying to comprehend what I’d just heard.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Well, if we watched the bride lament for twenty minutes about how she didn’t want to get married to the guy in the first place, how did it all end?”

“Oh,” I said.

“She gets married.”

“What?! Even if she didn’t want to?” she wondered, shocked.

“Yes,” I replied.

“That’s kind of the whole point. She didn’t have any choice. Her parents and the villagers found her a husband and decided she was going to get married. That’s it.”

“Wow,” she concluded. “That’s really sad.”

“Yes, I suppose it is,” I said.

“That’s a tale as old as time, though, and it’s not unique to Russian peasants, either. Millions of women have gone through this same experience. Very few women throughout history have gotten to choose their husbands or were even asked if they wanted to get married in the first place.”

“Hmm,” she mumbled, walking faster, at a more agitated pace. “Well, still… It’s sad.”

“Yes, it is,” I agreed.

To this day, I’m still haunted by the mystery of that weird, loud, confusing musical racket I barely understood. It was overwhelming, exhausting, and profound. It still is.

But when a mystery is too overpowering, one dare not disobey. You just sing.

Even if you have to sing while swallowing half your words and over-stressing your Ls like a poor, half-drunk Russian villager at a wedding for a random neighbor.

It's weird, nobody seems to understand it, it's in a language nobody speaks and almost no one understands, I have to stand in one place for four hours (which is the time it takes to fly 2/3rds across America)... um ... heck yeah, I'm in! When do we start!

Ron you have the spirit of an adventurer! Bravo!