Go Directly to Plato!

A cranky old woman’s note penciled on my philosophy paper was the most valuable lesson I ever learned in college.

Going to college was a strange and confusing experience for me. In 2003, I turned 18, and after leaving behind an entire life of being homeschooled, I went to “real” school for the first time ever.

I never graduated from high school, never received a diploma, and never took any college entrance exams like the SAT or ACT… but I did drive myself to a high school one afternoon that summer to take a GED (General Educational Development) test.

I got a passing score, so, as it turned out, I was now qualified to work at a fast-food joint “flipping burgers,” as they say.

But my parents told me “I was required” to go to college; this was not negotiable. When I went to the local community college to see about applying to go there, they were kind of confused.

“You don’t have a diploma?” they wondered.

“No, but I took a GED,” I responded.

“Okay, but that’s not good enough. We need to know where you’re at academically,” I was told.

They wanted to know what my SAT or ACT scores were, and when I told them I didn’t have any, they said I did have one other option: I could use the computer in their lobby to take a basic assessment right then and there.

So, I did. I sat at the computer for an hour or two and clicked on a bunch of screens with questions on them. It was weird: I had never taken a test on a computer before, and answering math questions that way seemed really hard for some reason. It felt unnatural to click on radio buttons or type out equations on a keyboard rather than write them out on paper like I always had in the past.

When it was all done, they congratulated me.

“Okay, now we know where to put you. The good news is you’re a pretty smart fella. The bad news is you are pretty awful at math, and you’ll need to take remedial classes.”

I had never heard of remedial classes, but what I learned was that I was so bad at math, I couldn’t even take the most basic, entry-level course. I had to take a few steps backward and review old math concepts I “should have already known by now.”

That was depressing. In an ideal world, I would have started with Math 121 (College Algebra), but I had to start with Math 090 (Introductory Algebra). I took that and passed with an “A.”

However, I had to advance to a second remedial class, Math 106 (Survey of Algebra), which I did not pass. I got an “F.” Then I took it a second time and passed with a “B.”

Only then could I finally advance to the entry-level math class I really should have taken in the first place, which was Math 121 (College Algebra). But it was too hard for me: I withdrew, so I got a grade of “W.”

I tried Math 121 a second time but still couldn’t figure it out, so I withdrew a second time and got a second “W.”

I tried Math 121 a third time, finally passing with a “C,” which meant that I now felt like Chris Farley’s buffoonish and naive character in the movie “Tommy Boy” — “I got a D+? I passed! I passed! Oh, man! I’m going to graduate!”

In case you’re counting, it took me six full semesters to finally pass what should have taken just one, which meant I wasted—and paid for—five entire semesters of community college just to catch up to where I should have been the first day I got there.

“So, what on earth does that have to do with angry ladies, philosophy, and Plato?” you might be wondering.

I’m getting to that.

As I was lighting my money on fire, paying for expensive do-overs on irrelevant math classes that I didn’t understand and couldn’t afford, while wasting my tender teenage years, staying up until 2:00 am trying to study but just crying at the pointlessness of it all… I was also taking other classes in the meantime.

Most of the classes I took at community college seemed completely useless for helping mold me as a future adult human being or a member of the workforce.

English 121 (English Composition) was the single most boring class I had (and have) ever taken in my entire life, and while I begrudgingly admit now that it did serve some use (this article is, technically, an “English composition,” after all), it was, in fact, so painfully lame and filled with such drudgery that I let the teacher know on the feedback form at the end of the semester. I wrote:

“This class is the most boring thing I have ever done in my entire life. All of us in this classroom would rather be doing anything on earth except sitting here right now, including brushing our teeth or sorting our underwear drawer. I almost feel like the real purpose of this class is to make us hate writing so much that we never write another paper again as long as we live.”

Looking back now, I have no idea how my professor took that kind of feedback. Who knows? I might have made her cry. I guess I’ll never know.

I feel kind of bad about that now… I didn’t want to hurt you, Mrs. Jones. You told us to be honest, so I was. But really, I’m still not sorry.

It felt like the actual purpose of this class was to destroy any fledgling passion for writing we may have already had, and it was supposed to give us some sort of “tough love” lesson about introducing us to “the real world.”

In a sense, if the very young Professor Jones’s intention was to give us all “shock therapy” as newbie students in order to kill our passion for creative writing, she certainly succeeded.

Over and over and over again, she hammered three major takeaways into our heads:

Always write in the third person.

Never write your own opinion on a topic. Find research done by experts and quote them.

Cite your sources.

She might as well have said: “Nobody cares what you think. Don’t write your own opinions. Just find out what other, smarter people have said about the topic you’re writing on, then offer some bland perspective or commentary while carefully pretending to be a neutral, unbiased, nameless source.”

In other words, “Write like an emotionless robot without any opinions,” she may as well have said. “Pretend you aren’t even human and use the perspective of a shapeless, formless, all-knowing god.”

This was all very hard for me to understand.

Why would we do that? Who on earth would want to read that? I wondered.

Had she ever read an article in Reader’s Digest, Popular Mechanics, Country Magazine, or… any other publication? Nobody writes like that!

That’s idiotic and BORING.

For one assignment, we were supposed to take a controversial topic and offer an even-handed treatment of the issue up for debate. I wrote about how Teacher’s Unions are nothing more than cabals of criminals who steal money from teachers and use heavy-handed thug tactics like tire-slashing in order to coerce people to become members against their will.

On a side note, I’m really impressed that I came to that conclusion—on my own—as early as two decades ago. You could see my budding libertarian streak start to reveal itself.

Hey, I even cited my sources! I quoted Rod Paige, the US Secretary of Education, who called the NEA (the National Education Association) a “terrorist organization.”

Mrs. Jones was quite harsh in her assessment of my work.

“This is definitely not a balanced treatment of your topic here. Unless I missed it, all I can find is the anti-union side.”

Also, she criticized me for writing in the “second person.”

Well, what was I supposed to do? We were tasked with finding arguments on both sides of an issue. I did. All the good arguments were on the side against teachers’ unions, and there were no good arguments in favor of them.

None. Zero. There still aren’t. Teachers’ unions are uniformly terrible. To be clear, teachers are often wonderful, but their labor unions are not. End of story. Twenty years later, I’m of the same opinion, only stronger.

So, I wrote honestly about that while, apparently, using a second-person narrative, which was against the rules. But guess what? Despite all that, she gave me a “B+” on the paper and an “A” in the course.

“That said,” she wrote, “your writing is quite good, and I have no problem rewarding that.”

What to make of all this? I’m still trying to make sense of it twenty years later. I do know this: I am damn proud of that paper. I still have it in my office. It almost brings a tear to my eye. I still don’t know what I was supposed to learn from that class other than: “Nobody writes the way we were taught in that class, so just ignore everything you learned.” That’s the working conclusion I have now until I can find a better one.

The other course I was taking at the same time was the polar opposite in almost every regard, and I couldn’t figure out how to reconcile the two.

Philosophy 111 (Introduction to Philosophy) was taught by Dr. Beardsley, a very old woman (no joke: she was 68 years old at the time) who was extremely irritable and cranky and openly chastised people for such cardinal sins as “rustling papers loudly.”

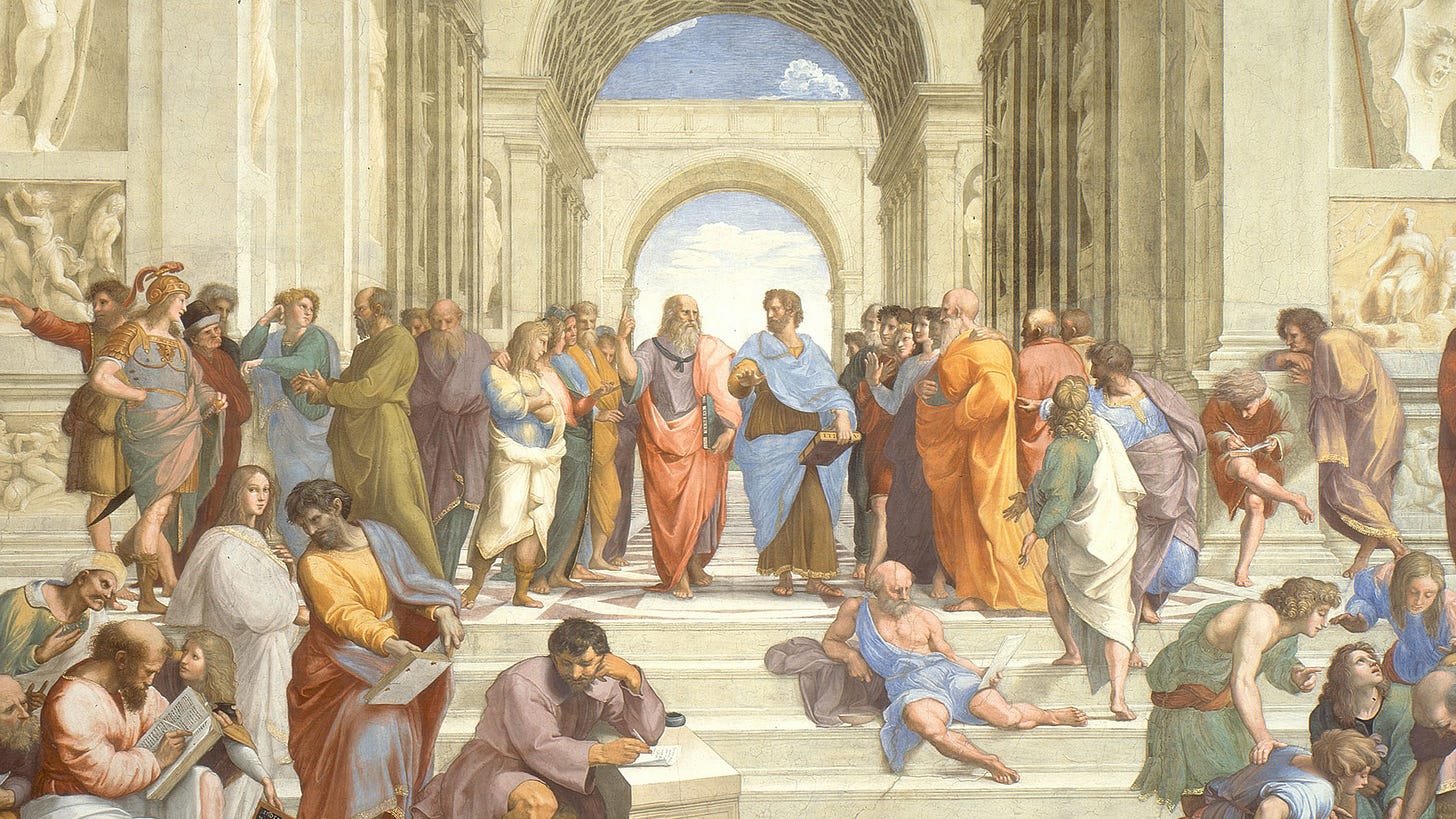

In this introductory course, we studied philosophers new and old, from ancient Greeks like Socrates, who said, “I know that I know nothing,” to French Existentialists from the 1940s like Sartre, who said, “Man is condemned to be free.”

Now, this was a class I was made for. I was stoked to study ancient thinkers of old: those who shaped Western Civilization as we know it today.

I DUG THIS MATERIAL, MAN.

This was the good stuff I had been waiting for. We talked at length about concepts such as wisdom and knowledge, good and evil, and even debated hypothetical riddles such as:

“Is the statement ‘Centaurs don’t take kindly the bridle’ true or false?”

Now, that was a puzzler! I loved this stuff.

It could be true if you were talking about mythical creatures like Centaurs in their mythical worlds and what we know about their supposed mythological personalities and preferences.

But hold on! Centaurs don’t even exist, so it can’t possibly be true!

And hold on even further! What does it even mean to “exist?” How do you define existence? Do Centaurs exist? Do you exist? Do I exist? How do you define “true?” How do you define “false?”

This was all extremely fascinating to me. If this is what college was all about, I wanted lots more of it.

For my final paper in this class, we had to choose a philosopher and a particular philosophical theory or perspective and write about it.

More than one person chose Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. I thought that was kind of interesting, but it didn’t thrill me. Others chose things that were so unremarkable that I don’t even remember them.

My choice was Plato’s “Theory of Forms,” which is, to quote Wikipedia (which we were never allowed to do in college): “Considered to be a classical solution to the problem of universals.”

I really liked this theory. I really liked Plato. I thought it was great.

I got a reference book from the school library, researched it, and read all about it and what other philosophers had to say about it.

The night before my paper was due, I stayed up until probably 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning writing about this wild new theory I’d discovered, finding out what the book said it meant, how it had been supported or debunked over the years, and more.

I did all the things the right way this time:

I wrote in the third person.

I didn’t write my own opinion on the topic. I found research done by experts and quoted them.

I cited my sources.

I was proud of my work. I turned it in, pleased that finally, I understood how to do this whole “college paper thing” now.

But when I got my paper back, the criticism stung.

Unlike Professor Jones, who used permanent red ink to issue her verdict on the worthiness of my writing, Dr. Beardsley always wrote her notes in light pencil marks that she told us we could simply erase if we didn’t agree with her assessment of what we thought. (That, in itself, is worthy of an entire article—perhaps another time.)

Her critique said (if I recall correctly):

“Why did you cite commentaries from other people? Why didn't you tell me your own opinion on the ‘Theory of Forms?’”

Ouch. I was floored.

At the very bottom of the page, she concluded, in all caps:

“GO DIRECTLY TO PLATO!”

Wow. I had missed the whole point of the assignment. I didn’t actually read any of Plato’s own words. I only read what other people wrote about what he said.

But I was so confused. Professor Jones would have been proud! Why did I have two professors giving me conflicting instructions?

They were both teaching basic, 100-level freshman classes, yet they were literally giving me instructions that were the exact opposite of each other.

Suffice it to say; I never took much stock in anything the boring Cahdi Jones taught me in her English 121 class with her notes in red ink. Who cared? Nothing she said was really memorable. As soon as that class was over, I unlearned most of what she taught me.

But what I gleaned from the grouchy Ruth Beardsley, who taught Philosophy 111, who was three times her age, who wrote in light pencil marks—who is now dead—changed my life forever. I think about what I learned in that class almost every day.

Whenever I’m studying a particular topic, I may still read a critical commentary on it by an expert, but I’m also extremely careful to read the actual source material, as her words still echo in my mind.

Because of this, instead of reading dumb commentaries ABOUT thinkers, I’ve tried hard to go directly TO them. Since that class, I’ve read at least 427 books or writings from people including Dante Alighieri, St. Augustine, Ulysses Grant, Rudyard Kipling, Abraham Lincoln, Richard Nixon, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Sun Tzu, Alexis de Tocqueville, Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, Cabeza de Vaca, Karl Marx, Adolf Hitler, Marcus Aurelius, Jimmy Carter, John Milton, Niccolò Machiavelli, and a lot more.

When you learn directly from people in the past, you can encounter their ideas yourself and form your own opinion without relying on other people to tell you what to think. That’s the most powerful way to learn that I know of.

“Go directly to Plato!”

Thanks, Dr. Beardsley.